Comparison of Related Sequences from Different Species Can Give Clues to Evolutionary Relationships Among Proteins

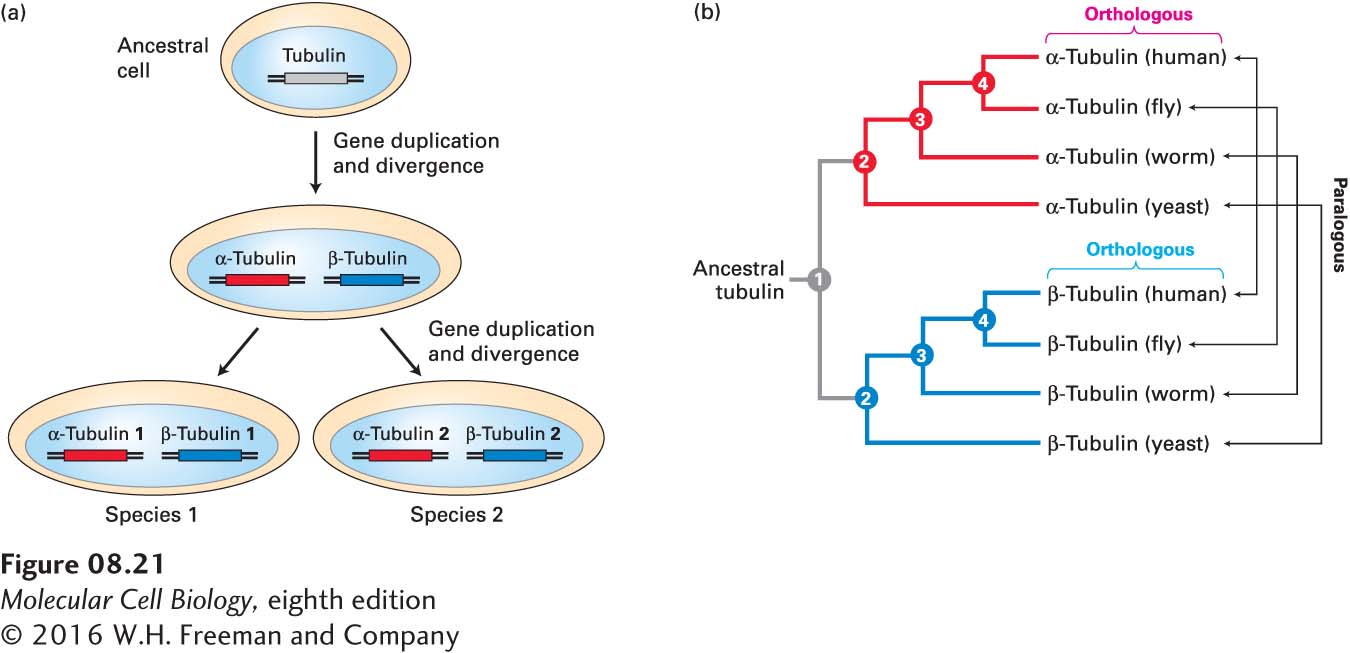

BLAST searches for related protein sequences may reveal that proteins belong to a protein family. Earlier, we considered gene families in a single organism, using the β-globin genes in humans as an example (see Figure 8-4a). But in a database that includes the genomic sequences of multiple organisms, protein families can also be recognized as being shared among related organisms. Consider, for example, the tubulin proteins, the basic subunits of microtubules, which are important components of the cytoskeleton (see Chapter 18). According to the simplified scheme in Figure 8-21a, the earliest eukaryotic cells are thought to have contained a single tubulin gene that was duplicated early in evolution; subsequent divergence of the different copies of the original tubulin gene formed the ancestral versions of the α- and β-tubulin genes. As different species diverged from these early eukaryotic cells, each of these gene sequences further diverged, giving rise to the slightly different forms of α-tubulin and β-tubulin now found in each species.

All the different members of the tubulin family of genes (and proteins) are sufficiently similar in sequence to suggest a common ancestral sequence. Thus all these sequences are considered to be homologous. More specifically, sequences that presumably diverged as a result of gene duplication (e.g., the α- and β-tubulin sequences) are described as paralogous. Sequences that arose because of speciation (e.g., the α-tubulin genes in different species) are described as orthologous. From the degree of sequence relatedness of the tubulins present in different organisms today, evolutionary relationships can be deduced, as illustrated in Figure 8-21b. Of the three types of sequence relationships, orthologous sequences are the most likely to share the same function.