18-1 Should Policy Be Active or Passive?

Policymakers in the federal government view economic stabilization as one of their primary responsibilities. The analysis of macroeconomic policy is a regular duty of the Council of Economic Advisers, the Congressional Budget Office, the Federal Reserve, and other government agencies. As we have seen in the preceding chapters, monetary and fiscal policy can exert a powerful impact on aggregate demand and, thereby, on inflation and unemployment. When Congress or the president is considering a major change in fiscal policy, or when the Federal Reserve is considering a major change in monetary policy, foremost in the discussion are how the change will influence inflation and unemployment and whether aggregate demand needs to be stimulated or restrained.

Although the government has long conducted monetary and fiscal policy, the view that it should use these policy instruments to try to stabilize the economy is more recent. The Employment Act of 1946 was a landmark piece of legislation in which the government first held itself accountable for macroeconomic performance. The act states that “it is the continuing policy and responsibility of the Federal Government to … promote full employment and production.” This law was written when the memory of the Great Depression was still fresh. The lawmakers who wrote it believed, as many economists do, that in the absence of an active government role in the economy, events like the Great Depression could occur regularly.

To many economists the case for active government policy is clear and simple. Recessions are periods of high unemployment, low incomes, and increased economic hardship. The model of aggregate demand and aggregate supply shows how shocks to the economy can cause recessions. It also shows how monetary and fiscal policy can prevent (or at least soften) recessions by responding to these shocks. These economists consider it wasteful not to use these policy instruments to stabilize the economy.

Other economists are critical of the government’s attempts to stabilize the economy. These critics argue that the government should take a hands-off approach to macroeconomic policy. At first, this view might seem surprising. If our model shows how to prevent or reduce the severity of recessions, why do these critics want the government to refrain from using monetary and fiscal policy for economic stabilization? To find out, let’s consider some of their arguments.

533

Lags in the Implementation and Effects of Policies

Economic stabilization would be easy if the effects of policy were immediate. Making policy would be like driving a car: policymakers would simply adjust their instruments to keep the economy on the desired path.

Making economic policy, however, is less like driving a car than it is like piloting a large ship. A car changes direction almost immediately after the steering wheel is turned. By contrast, a ship changes course long after the pilot adjusts the rudder, and once the ship starts to turn, it continues turning long after the rudder is set back to normal. A novice pilot is likely to oversteer and, after noticing the mistake, overreact by steering too much in the opposite direction. The ship’s path could become unstable, as the novice responds to previous mistakes by making larger and larger corrections.

Like a ship’s pilot, economic policymakers face the problem of long lags. Indeed, the problem for policymakers is even more difficult, because the lengths of the lags are hard to predict. These long and variable lags greatly complicate the conduct of monetary and fiscal policy.

Economists distinguish between two lags that are relevant for the conduct of stabilization policy: the inside lag and the outside lag. The inside lag is the time between a shock to the economy and the policy action responding to that shock. This lag arises because it takes time for policymakers first to recognize that a shock has occurred and then to put appropriate policies into effect. The outside lag is the time between a policy action and its influence on the economy. This lag arises because policies do not immediately influence spending, income, and employment.

A long inside lag is a central problem with using fiscal policy for economic stabilization. This is especially true in the United States, where changes in spending or taxes require the approval of the president and both houses of Congress. The slow and cumbersome legislative process often leads to delays, which make fiscal policy an imprecise tool for stabilizing the economy. This inside lag is shorter in countries with parliamentary systems, such as the United Kingdom, because there the party in power can often enact policy changes more rapidly.

Monetary policy has a much shorter inside lag than fiscal policy because a central bank can decide on and implement a policy change in less than a day, but monetary policy has a substantial outside lag. Monetary policy works by changing the money supply and interest rates, which in turn influence investment and aggregate demand. Many firms make investment plans far in advance, however, so a change in monetary policy is thought not to affect economic activity until about six months after it is made.

The long and variable lags associated with monetary and fiscal policy certainly make stabilizing the economy more difficult. Advocates of passive policy argue that, because of these lags, successful stabilization policy is almost impossible. Indeed, attempts to stabilize the economy can be destabilizing. Suppose that the economy’s condition changes between the beginning of a policy action and its impact on the economy. In this case, active policy may end up stimulating the economy when it is heating up or depressing the economy when it is cooling off. Advocates of active policy admit that such lags do require policymakers to be cautious. But, they argue, these lags do not necessarily mean that policy should be completely passive, especially in the face of a severe and protracted economic downturn, such as the recession that began in 2008.

534

Some policies, called automatic stabilizers, are designed to reduce the lags associated with stabilization policy. Automatic stabilizers are policies that stimulate or depress the economy when necessary without any deliberate policy change. For example, the system of income taxes automatically reduces taxes when the economy goes into a recession: without any change in the tax laws, individuals and corporations pay less tax when their incomes fall. Similarly, the unemployment-insurance and welfare systems automatically raise transfer payments when the economy moves into a recession because more people apply for benefits. One can view these automatic stabilizers as a type of fiscal policy without any inside lag.

The Difficult Job of Economic Forecasting

Because policy influences the economy only after a long lag, successful stabilization policy requires the ability to accurately predict future economic conditions. If we cannot predict whether the economy will be in a boom or a recession in six months or a year, we cannot evaluate whether monetary and fiscal policy should now be trying to expand or contract aggregate demand. Unfortunately, economic developments are often unpredictable, at least given our current understanding of the economy.

One way forecasters try to look ahead is with leading indicators. As we discussed in Chapter 10, a leading indicator is a data series that fluctuates in advance of the economy. A large fall in a leading indicator signals that a recession is more likely to occur in the coming months.

Another way forecasters look ahead is with macroeconometric models, which have been developed both by government agencies and by private firms. A macroeconometric model is a model that describes the economy quantitatively, rather than just qualitatively. Many of these models are essentially more complicated and more realistic versions of the dynamic model of aggregate demand and aggregate supply we learned about in Chapter 15. The economists who build macroeconometric models use historical data to estimate the model’s parameters. Once a model is built, economists can simulate the effects of alternative policies. The model can also be used for forecasting. After the model’s user makes assumptions about the path of the exogenous variables, such as monetary policy, fiscal policy, and oil prices, the model yields predictions about unemployment, inflation, and other endogenous variables. Keep in mind, however, that the validity of these predictions is only as good as the model and the forecasters’ assumptions about the exogenous variables.

535

CASE STUDY

Mistakes in Forecasting

“Light showers, bright intervals, and moderate winds.” This was the forecast offered by the renowned British national weather service on October 14, 1987. The next day Britain was hit by its worst storm in more than two centuries.

Like weather forecasts, economic forecasts are a crucial input to private and public decisionmaking. Business executives rely on economic forecasts when deciding how much to produce and how much to invest in plant and equipment. Government policymakers also rely on forecasts when developing economic policies. Unfortunately, like weather forecasts, economic forecasts are far from precise.

The most severe economic downturn in U.S. history, the Great Depression of the 1930s, caught economic forecasters completely by surprise. Even after the stock market crash of 1929, they remained confident that the economy would not suffer a substantial setback. In late 1931, when the economy was clearly in bad shape, the eminent economist Irving Fisher predicted that it would recover quickly. Subsequent events showed that these forecasts were much too optimistic: the unemployment rate continued to rise until 1933 when it hit 25 percent, and it remained elevated for the rest of the decade.1

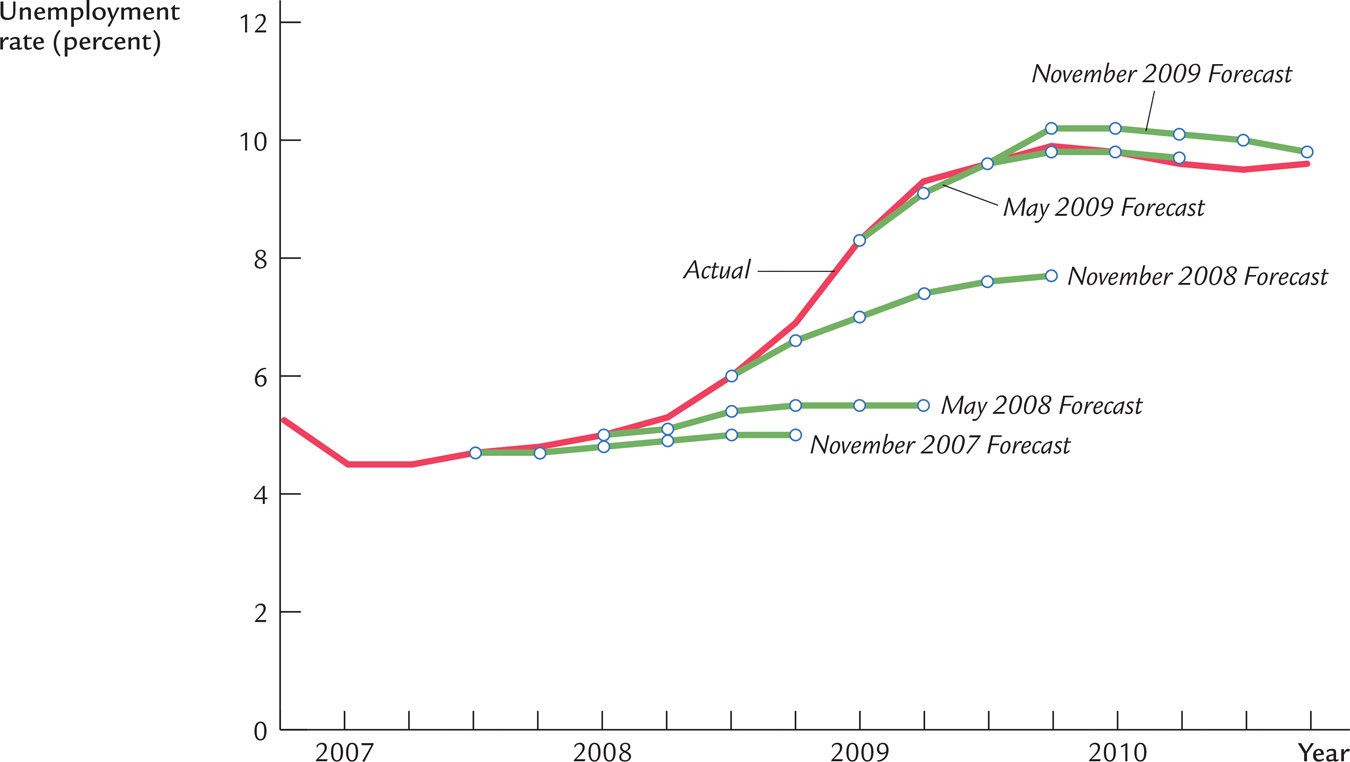

Figure 18-1 shows how economic forecasters did during the recession of 2008–2009, the most severe economic downturn in the United States since the Great Depression. This figure shows the actual unemployment rate (in red) and several attempts to predict it for the following five quarters (in green). You can see that the forecasters did well when predicting unemployment one or two quarters ahead. The more distant forecasts, however, were often inaccurate. The November 2007 Survey of Professional Forecasters predicted a slowdown, but only a modest one: the U.S. unemployment rate was projected to increase from 4.7 percent in the fourth quarter of 2007 to 5.0 percent in the fourth quarter of 2008. By the May 2008 survey, the forecasters had raised their predictions for unemployment at the end of the year, but only to 5.5 percent. In fact, the unemployment rate was 6.9 percent in the last quarter of 2008. The forecasters became more pessimistic as the recession unfolded, but still not pessimistic enough. In November 2008, they predicted that the unemployment rate would rise to 7.7 percent in the fourth quarter of 2009. In fact, it rose to about 10 percent.

FIGURE 18-1

536

The Great Depression of the 1930s and the Great Recession of 2008–2009 show that many of the most dramatic economic events are unpredictable. Private and public decisionmakers have little choice but to rely on economic forecasts, but they must always keep in mind that these forecasts come with a large margin of error.

Ignorance, Expectations, and the Lucas Critique

The prominent economist Robert Lucas once wrote, “As an advice-giving profession we are in way over our heads.” Even many of those who advise policymakers would agree with this assessment. Economics is a young science, and there is still much that we do not know. Economists cannot be completely confident when they assess the effects of alternative policies. This ignorance suggests that economists should be cautious when offering policy advice.

In his writings on macroeconomic policymaking, Lucas has emphasized that economists need to pay more attention to the issue of how people form expectations of the future. Expectations play a crucial role in the economy because they influence all sorts of behavior. For instance, households decide how much to consume based on how much they expect to earn in the future, and firms decide how much to invest based on their expectations of future profitability. These expectations depend on many things, but one factor, according to Lucas, is especially important: the policies being pursued by the government. When policymakers estimate the effect of any policy change, therefore, they need to know how people’s expectations will respond to the policy change. Lucas has argued that traditional methods of policy evaluation—such as those that rely on standard macroeconometric models—do not adequately take into account the impact of policy on expectations. This criticism of traditional policy evaluation is known as the Lucas critique.2

537

An important example of the Lucas critique arises in the analysis of disinflation. As you may recall from Chapter 14, the cost of reducing inflation is often measured by the sacrifice ratio, which is the number of percentage points of GDP that must be forgone to reduce inflation by 1 percentage point. Because estimates of the sacrifice ratio are often large, they have led some economists to argue that policymakers should learn to live with inflation, rather than incur the large cost of reducing it.

According to advocates of the rational-expectations approach, however, these estimates of the sacrifice ratio are unreliable because they are subject to the Lucas critique. Traditional estimates of the sacrifice ratio are based on adaptive expectations, that is, on the assumption that expected inflation depends on past inflation. Adaptive expectations may be a reasonable premise in some circumstances, but if the policymakers make a credible change in policy, workers and firms setting wages and prices will rationally respond by adjusting their expectations of inflation appropriately. This change in inflation expectations will quickly alter the short-run tradeoff between inflation and unemployment. As a result, reducing inflation can potentially be much less costly than is suggested by traditional estimates of the sacrifice ratio.

The Lucas critique leaves us with two lessons. The narrow lesson is that economists evaluating alternative policies need to consider how policy affects expectations and, thereby, behavior. The broad lesson is that policy evaluation is hard, so economists engaged in this task should be sure to show the requisite humility.

The Historical Record

In judging whether government policy should play an active or passive role in the economy, we must give some weight to the historical record. If the economy has experienced many large shocks to aggregate supply and aggregate demand, and if policy has successfully insulated the economy from these shocks, then the case for active policy should be clear. Conversely, if the economy has experienced few large shocks, and if the fluctuations we have observed can be traced to inept economic policy, then the case for passive policy should be clear. In other words, our view of stabilization policy should be influenced by whether policy has historically been stabilizing or destabilizing. For this reason, the debate over macroeconomic policy frequently turns into a debate over macroeconomic history.

538

Yet history does not settle the debate over stabilization policy. Disagreements over history arise because it is not easy to identify the sources of economic fluctuations. The historical record often permits more than one interpretation.

The Great Depression is a case in point. Economists’ views on macroeconomic policy are often related to their views on the cause of the Depression. Some economists believe that a large contractionary shock to private spending caused the Depression. They assert that policymakers should have responded by using the tools of monetary and fiscal policy to stimulate aggregate demand. Other economists believe that the large fall in the money supply caused the Depression. They assert that the Depression would have been avoided if the Fed had been pursuing a passive monetary policy of increasing the money supply at a steady rate. Hence, depending on one’s beliefs about its cause, the Great Depression can be viewed either as an example of why active monetary and fiscal policy is necessary or as an example of why it is dangerous.

CASE STUDY

Is the Stabilization of the Economy a Figment of the Data?

Keynes wrote The General Theory in the 1930s, and in the wake of the Keynesian revolution, governments around the world began to view economic stabilization as a primary responsibility. Some economists believe that the development of Keynesian theory has had a profound influence on the behavior of the economy. Comparing data from before World War I and after World War II, they find that real GDP and unemployment have become much more stable. This, some Keynesians claim, is the best argument for active stabilization policy: it has worked.

In a series of provocative and influential papers, economist Christina Romer has challenged this assessment of the historical record. She argues that the measured reduction in volatility reflects not an improvement in economic policy and performance but rather an improvement in the economic data. The older data are much less accurate than the newer data. Romer claims that the higher volatility of unemployment and real GDP reported for the period before World War I is largely a figment of the data.

Romer uses various techniques to make her case. One is to construct more accurate data for the earlier period. This task is difficult because data sources are not readily available. A second way is to construct less accurate data for the recent period—that is, data that are comparable to the older data and thus suffer from the same imperfections. After constructing new “bad” data, Romer finds that the recent period appears almost as volatile as the early period, suggesting that the volatility of the early period may be largely an artifact of how the data were assembled.

539

Romer’s work is part of the continuing debate over whether macroeconomic policy has improved the performance of the economy. Although her work remains controversial, most economists now believe that the economy in the immediate aftermath of the Keynesian revolution was only slightly more stable than it had been before.3

CASE STUDY

How Does Policy Uncertainty Affect the Economy?

When monetary and fiscal policymakers actively try to control the economy, the future course of economic policy is often uncertain. Policymakers do not always make their intentions clear. Moreover, because the policy outcome can be the result of a divisive, contentious, and unpredictable political process, the public has every reason to be unsure about what policy decisions will end up being made.

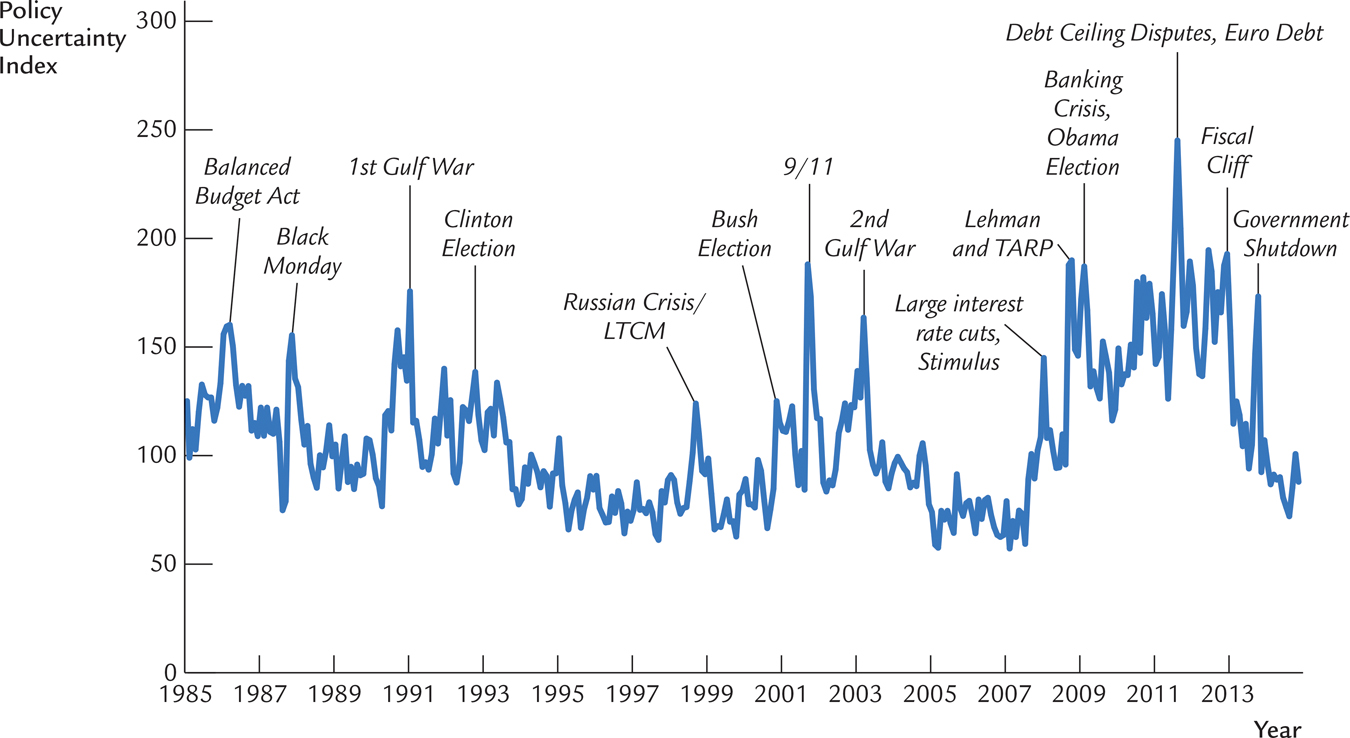

In recent research, economists Scott Baker, Nicholas Bloom, and Steve Davis studied the effects of policy uncertainty. Baker, Bloom, and Davis began by constructing an index that measures how the amount of policy uncertainty changes over time. Their index has three components.

The first component is derived from reading articles in newspapers. Starting in January 1985, they searched ten major papers for terms related to economic and policy uncertainty. In particular, they searched for articles containing the term “uncertainty” or “uncertain,” the term “economic” or “economy,” and at least one of the following terms: “congress,” “legislation,” “white house,” “regulation,” “federal reserve,” or “deficit.” The more articles there were that included terms in all three categories, the higher the index of policy uncertainty.

The second component of the index is based on the number of temporary provisions in the federal tax code. Baker, Bloom, and Davis reasoned that “temporary tax measures are a source of uncertainty for businesses and households because Congress often extends them at the last minute, undermining stability in and certainty about the tax code.” The more temporary tax provisions there are, and the larger the dollar magnitudes involved in the provisions, the higher the index of policy uncertainty.

The third component of the index is based on the amount of disagreement among private forecasters about several key variables related to macroeconomic policy. Baker, Bloom, and Davis assumed that the more private forecasters disagree about the future price level and future levels of government spending, the more uncertainty there is about monetary and fiscal policy. That is, the greater the dispersion in these private forecasts, the higher the level of the policy uncertainty index.

Figure 18-2 shows the index derived from these three components. The index spikes upward, indicating an increase in policy uncertainty, when there is a significant foreign policy event (such as war or terrorist attack), when there is an economic crisis (such as the Black Monday stock market crash or the bankruptcy of the large investment bank Lehman Brothers), or when there is a major political event (such as the election of a new president).

FIGURE 18-2

540

With this index in hand, Baker, Bloom, and Davis then investigated how policy uncertainty correlates with macroeconomic performance. They found that higher uncertainty about economic policy depresses the economy. In particular, when economic policy uncertainty rises, investment, production, and employment are likely to decline over the next year (relative to their normal growth).

One possible explanation for this effect is that uncertainty may depress the aggregate demand for goods and services. When policy uncertainty increases, households and firms may put off some large purchases until the uncertainty is resolved. For example, if a firm is considering building a new factory, and the profitability of the investment depends on what policy is pursued, the firm may decide to wait until a policy decision is made. Such a delay is rational for the firm, but it contributes to a decline in aggregate demand, which reduces the economy’s output and raises unemployment.

To be sure, some policy uncertainty is inevitable. But it is good for policymakers to keep in mind that the amount of uncertainty is, to some degree, under their control and that heightened uncertainty appears to have adverse macroeconomic effects.4

541