A History of Western Society: Printed Page 146

A History of Western Society, Value Edition: Printed Page 151

Civil War

The history of the late republic is the story of power struggles among many famous Roman figures against a background of unrest at home and military campaigns abroad. This led to a series of bloody civil wars that raged from Spain across northern Africa to Egypt.

Sulla’s political heirs were Pompey, Crassus, and Julius Caesar, all of them able military leaders and brilliant politicians. Pompey (106–48 B.C.E.) began a meteoric rise to power as a successful commander of troops for Sulla against Marius in Italy, Sicily, and Africa. He then suppressed a rebellion in Spain, led naval forces against pirates in the Mediterranean, and in 67 B.C.E. was sent by the Senate to command Roman forces in the East. He defeated Mithridates and the forces of other rulers as well, transforming their territories into Roman provinces.

Crassus (ca. 115–53 B.C.E.) also began his military career under Sulla and became the wealthiest man in Rome through buying and selling land. In 73 B.C.E. a major slave revolt broke out in Italy, led by Spartacus, a former gladiator. The slave armies, which eventually numbered in the tens of thousands, defeated several Roman units sent to quash them. Finally Crassus led a large army against them and put down the revolt. Spartacus was apparently killed on the battlefield, and the slaves who were captured were crucified, with thousands of crosses lining the main road to Rome.

Pompey and Crassus then made an informal agreement with the populares in the Senate. Both were elected consuls in 70 B.C.E. and began to dismantle Sulla’s constitution and initiate economic and political reforms once again. They and the Senate moved too slowly for some people, however, who planned an uprising. This plot was discovered, and the forces of the rebels were put down in 63 B.C.E. by an army sent by Cicero (106–43 B.C.E.), a leader of the optimates who was consul at the time. The rebellion and Cicero’s skillful handling of it discredited the populares.

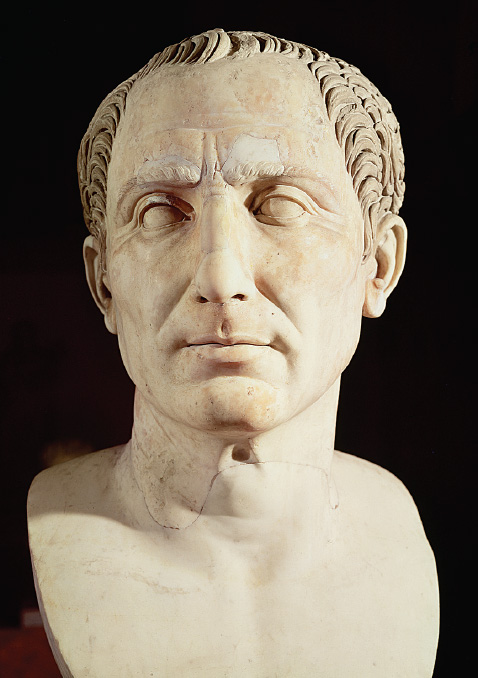

The man who cast the longest shadow over these troubled years was Julius Caesar (100–44 B.C.E.). Born of a noble family, he received an excellent education, which he furthered by studying in Greece with some of the most eminent teachers of the day. He had serious intellectual interests and immense literary ability. His account of his military operations in Gaul (present-day France), the Commentaries on the Gallic Wars, became a classic of Western literature. Caesar was a superb orator, and his personality and wit made him popular. Military service was an effective stepping-stone to politics, and Caesar was a military genius who knew how to win battles and turn victories into permanent gains. He was also a shrewd politician of unbridled ambition, who knew how to use the patron-client system to his advantage. He became a protégé of Crassus, who provided cash for Caesar’s needs, and at the same time helped the careers of other politicians, who in turn looked to Caesar’s interests in Rome when he was away from the city. Caesar launched his military career in Spain, where his courage won the respect and affection of his troops.

In 60 B.C.E. Caesar returned to Rome from Spain and Pompey returned from military victories in the east. Together with Crassus, the three concluded an informal political alliance later termed the First Triumvirate (trigh-UHM-veh-ruht), in which they agreed to advance one another’s interests. Crassus’s money helped Caesar be elected consul, and Pompey married Caesar’s daughter Julia. Crassus was appointed governor of Syria, Pompey of Hispania (present-day Spain), and Caesar of Gaul.

Personal ambitions undermined the First Triumvirate. While Caesar was away from Rome fighting in Gaul, his supporters formed gangs that attacked the supporters of Pompey. These were countered by supporters of Pompey, and there were riots in the streets of Rome. The First Triumvirate disintegrated. Crassus died in battle while trying to conquer Parthia, and Caesar and Pompey accused each other of treachery. Fearful of Caesar’s popularity and growing power, the Senate sided with Pompey and ordered Caesar to disband his army. He refused, and instead in 49 B.C.E. he crossed the Rubicon River in northern Italy — the boundary of his territorial command — with soldiers. (“Crossing the Rubicon” is still used as an expression for committing to an irreversible course of action.) Although their forces outnumbered Caesar’s, Pompey and the Senate fled Rome, and Caesar entered the city without a fight.

Caesar then led his army against those loyal to Pompey and the Senate in Spain and Greece. In 48 B.C.E., despite being outnumbered, he defeated Pompey and his army at the Battle of Pharsalus in central Greece. Pompey fled to Egypt, which was embroiled in a battle for control not between two generals, but between a brother and sister, Ptolemy XIII and Cleopatra VII (69–30 B.C.E.). Caesar followed Pompey to Egypt, Cleopatra allied herself with Caesar, and Caesar’s army defeated Ptolemy’s army, ending the power struggle. Pompey was assassinated in Egypt, Cleopatra and Caesar became lovers, and Caesar brought Cleopatra to Rome. (See “Individuals in Society: Queen Cleopatra.”) Caesar put down a revolt against Roman control by the king of Pontus in northern Turkey, then won a major victory over Pompey’s army — now commanded by his sons — in Spain.

In the middle of defeating his enemies in battles all around the Mediterranean (see Map 5.2), Julius Caesar returned to Rome several times and was elected or appointed to various positions, including consul and dictator. He was acclaimed imperator, a title given to victorious military commanders and a term that later gave rise to the word emperor. Sometimes these elections happened when Caesar was away fighting; they were often arranged by his chief supporter and client in Rome, Mark Antony (83–30 B.C.E.), who was himself a military commander. Whatever Caesar’s official position, after he crossed the Rubicon he simply made changes on his own authority, though often with the approval of the Senate, which he packed with his supporters. The Senate transformed his temporary positions as consul and dictator into ones he would hold for life.

Caesar began to make a number of legal and economic reforms. He issued laws about debt, the collection of taxes, and the distribution of grain and land. Families who had many children were to receive rewards, and Roman allies in Italy were to have full citizenship. He reformed the calendar, which had been based on the cycles of the moon, by replacing it with one based on the sun, adapted from the Egyptian calendar. He sponsored celebrations honoring his victories, had coins struck with his portrait, and founded new colonies, which were to be populated by veterans and the poor. He planned even more changes, including transforming elected positions such as consul, tribune, and provincial governor into ones that he appointed.

Caesar was wildly popular with most people in Rome, and even with many senators. Other senators, led by Brutus and Cassius, two patricians who favored the traditional republic, opposed his rise to what was becoming absolute power. In 44 B.C.E. they conspired to kill him and did so on March 15 — a date called the “Ides of March” in the Roman calendar — stabbing him multiple times on the steps of the theatre of Pompey, where the Senate was meeting that day.

The conspiring senators called themselves the “Liberators” and said they were defending the liberties of the Roman Republic, but their support for the traditional power of the Senate could do little to save Rome from its pattern of misgovernment. The result of the assassination was another round of civil war. (See “Primary Source 5.5: Cicero and the Plot to Kill Caesar.”) Caesar had named his eighteen-year-old grandnephew and adopted son, Octavian, as his heir. In 43 B.C.E. Octavian joined forces with Mark Antony and another of Caesar’s lieutenants, Lepidus (LEH-puh-duhs), in a formal pact known later as the Second Triumvirate. Together they hunted down Caesar’s killers and defeated the military forces loyal to Pompey’s sons and to the conspirators. They agreed to divide the provinces into spheres of influence, with Octavian taking most of the west, Antony the east, and Lepidus the Iberian Peninsula and North Africa. The three came into conflict, and Lepidus was forced into exile by Octavian, leaving the other two to confront one another.

Both Octavian and Antony set their sights on gaining more territory. Cleopatra had returned to rule Egypt after Caesar’s death, and supported Antony, who became her lover as well as her ally. In 31 B.C.E. Octavian’s forces defeated the combined forces of Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium in Greece, but the two escaped. Octavian pursued them to Egypt, and they committed suicide rather than fall into his hands. Octavian’s victory at Actium put an end to an age of civil war. For his success, the Senate in 27 B.C.E. gave Octavian the name Augustus, meaning “revered one.” Although the Senate did not mean this to be a decisive break with tradition, that date is generally used to mark the end of the Roman Republic and the start of the Roman Empire.