A History of Western Society: Printed Page 519

A History of Western Society, Value Edition: Printed Page 502

A History of Western Society, Concise Edition: Printed Page 522

The Influence of the Philosophes

Divergences among the early thinkers of the Enlightenment show that, while they shared many of the same premises and questions, the answers they found differed widely. The spread of this spirit of inquiry owed a great deal to the work of the philosophes (fee-

Philosophe is the French word for “philosopher,” and in the mid-

To appeal to the public and get around the censors, the philosophes wrote novels and plays, histories and philosophies, and dictionaries and encyclopedias, all filled with satire and double meanings to spread their message. One of the greatest philosophes, the baron de Montesquieu (mahn-

Major Figures of the Enlightenment

| Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677) | Early Enlightenment thinker excommunicated from the Jewish religion for his concept of a deterministic universe |

| John Locke (1632–1704) | Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690) |

| Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz (1646–1716) | German philosopher and mathematician known for his optimistic view of the universe |

| Pierre Bayle (1647–1706) | Historical and Critical Dictionary (1697) |

| Montesquieu (1689–1755) | The Persian Letters (1721); The Spirit of Laws (1748) |

| Voltaire (1694–1778) | Renowned French philosophe and author of more than seventy works |

| David Hume (1711–1776) | Central figure of the Scottish Enlightenment; Of Natural Characters (1748) |

| Jean- |

The Social Contract (1762) |

| Denis Diderot (1713–1784) and Jean le Rond d’Alembert (1717–1783) | Editors of Encyclopedia: The Rational Dictionary of the Sciences, the Arts, and the Crafts (1751–1772) |

| Adam Smith (1723–1790) | The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759); An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776) |

| Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) | What Is Enlightenment? (1784); On the Different Races of Man (1775) |

| Moses Mendelssohn (1729–1786) | Major philosopher of the Haskalah, or Jewish Enlightenment |

| Cesare Beccaria (1738–1794) | On Crimes and Punishments (1764) |

Disturbed by the growth in absolutism under Louis XIV and inspired by the example of the physical sciences, he set out to apply the critical method to the problem of government in The Spirit of Laws (1748). Arguing that forms of government were shaped by history and geography, Montesquieu identified three main types: monarchies, republics, and despotisms. A great admirer of the English parliamentary system, Montesquieu argued for a separation of powers, with political power divided among different classes and legal estates holding unequal rights and privileges. Montesquieu was no democrat; he was apprehensive about the uneducated poor and he did not question the sovereignty of the French monarchy. But he was concerned that absolutism in France was drifting into tyranny and believed that strengthening the influence of intermediary powers was the best way to prevent it. Decades later, his theory of separation of powers had a great impact on the constitutions of the young United States in 1789 and of France in 1791.

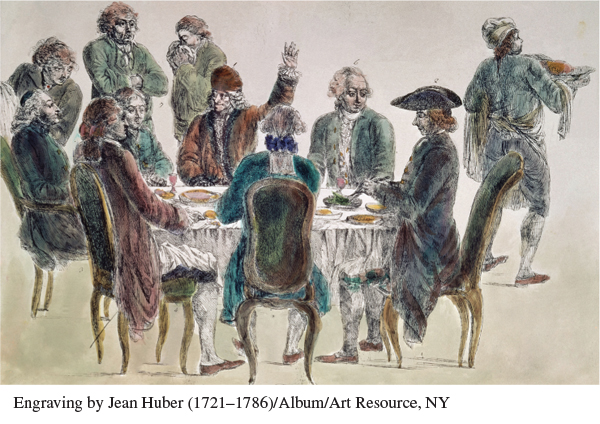

The most famous philosophe was François Marie Arouet, known by the pen name Voltaire (vohl-

Returning to France, Voltaire met Gabrielle-

While living at Cirey, Voltaire wrote works praising England and popularizing English science. Yet, like almost all of the philosophes, Voltaire was a reformer, not a revolutionary, in politics. He pessimistically concluded that the best one could hope for in the way of government was a good monarch, since human beings “are very rarely worthy to govern themselves.” Nor did Voltaire believe in social and economic equality. The only realizable equality, Voltaire thought, was that “by which the citizen only depends on the laws which protect the freedom of the feeble against the ambitions of the strong.”6

Voltaire’s philosophical and religious positions were much more radical. Voltaire believed in God, but he rejected Catholicism in favor of deism, belief in a distant noninterventionist deity. Drawing on mechanistic philosophy, he envisioned a universe in which God acted like a great clockmaker who built an orderly system and then stepped aside to let it run. Above all, Voltaire and most of the philosophes hated all forms of religious intolerance, which they believed led to fanaticism and cruelty. (See “Thinking Like a Historian: The Enlightenment Debate on Religious Intolerance.”)

The strength of the philosophes lay in their dedication and organization. Their greatest achievement was a group effort — the seventeen-

Completed in 1765 despite opposition from the French state and the Catholic Church, the Encyclopedia contained seventy-

After about 1770 a number of thinkers and writers began to attack the philosophes’ faith in reason and progress. The most famous of these was Jean-

Like other Enlightenment thinkers, Rousseau was passionately committed to individual freedom. Unlike them, however, he attacked rationalism and civilization as destroying, rather than liberating, the individual. Warm, spontaneous feeling, Rousseau believed, had to complement and correct cold intellect. Moreover, he asserted, the basic goodness of the individual and the unspoiled child had to be protected from the cruel refinements of civilization. Rousseau’s ideals greatly influenced the early Romantic movement, which rebelled against the culture of the Enlightenment in the late eighteenth century.

Rousseau’s contribution to political theory in The Social Contract (1762) was based on two fundamental concepts: the general will and popular sovereignty. According to Rousseau, the general will is sacred and absolute, reflecting the common interests of all the people, who have displaced the monarch as the holder of sovereign power. The general will is not necessarily the will of the majority, however. At times the general will may be the authentic, long-