A History of Western Society: Printed Page 1053

A History of Western Society, Value Edition: Printed Page 1015

A History of Western Society, Concise Edition: Printed Page 1060

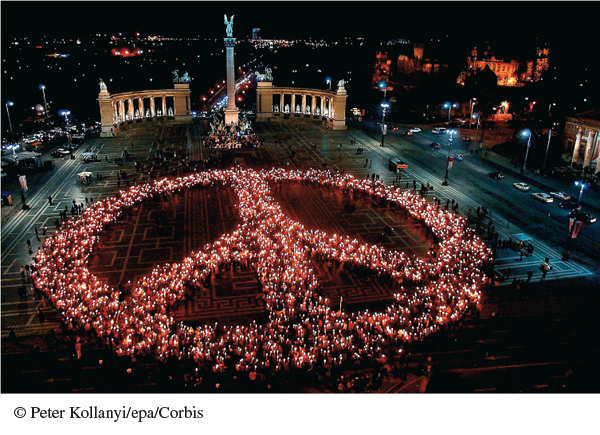

Promoting Human Rights

Though regional differences persisted in the twenty-

European leaders and humanitarians believed that more global agreements and new international institutions were needed to set moral standards and to regulate countries, leaders, armies, corporations, and individuals. In practice, this meant more curbs on the sovereign rights of the world’s states, just as the states of the European Union had imposed increasingly strict standards of behavior on themselves in order to secure the rights and welfare of EU citizens. As one EU official concluded, the European Union has a “historical responsibility” to make morality “a basis of policy” because “human rights are more important than states’ rights.”21

In practical terms, this mission raised questions. Europe’s evolving human rights policies would require military intervention to stop civil wars and to prevent tyrannical governments from slaughtering their own people. Thus the EU joined the United States to intervene militarily to stop the killing and protect minority rights in Bosnia, Croatia, and Kosovo. The EU states vigorously supported UN initiatives to verify compliance with anti–germ warfare conventions, outlaw the use of land mines, and establish a new international court to prosecute war criminals.

Europeans also broadened definitions of individual rights. Having abolished the death penalty in the EU, they condemned its continued use in China, the United States, and other countries. At home, Europe expanded personal rights. The pacesetting Netherlands gave pensions and workers’ rights to prostitutes and provided assisted suicide (euthanasia) for the terminally ill. The Dutch recognized same-

Europeans extended their broad-

The record was not always perfect. Critics accused the European Union (and the United States) of selectively promoting human rights in their differential responses to the Arab Spring — the West was willing to act in some cases, as in Libya, but dragged its feet in others, as in Egypt and Syria. The conflicted response to the immigration emergency of 2015 underscored the difficulties of shaping unified human rights policies that would satisfy competing political and national interests. Attempts to extend rights to women, indigenous peoples, and immigrants remained controversial. Even so, the general trend suggested that Europe’s leaders and peoples alike took very seriously the ideals articulated in the 1948 UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights.