A History of Western Society: Printed Page 77

A History of Western Society, Value Edition: Printed Page 74

A History of Western Society, Concise Edition: Printed Page 79

Athenian Arts in the Age of Pericles

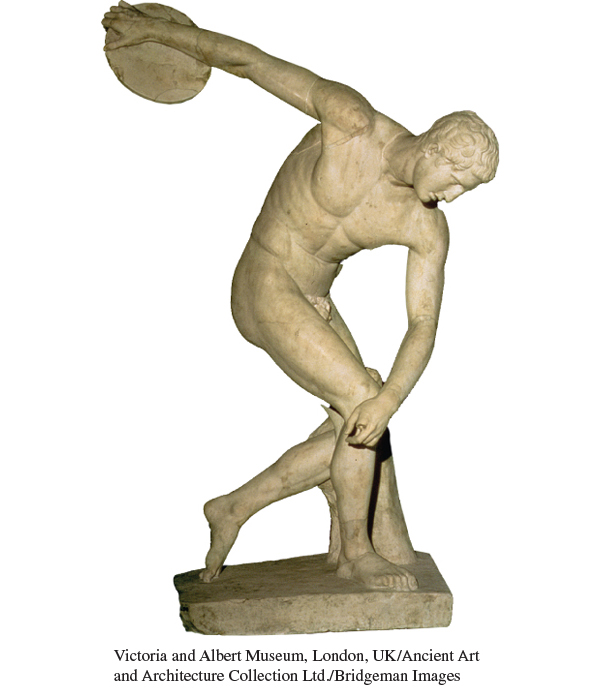

In the midst of the warfare of the fifth century B.C.E., Pericles turned Athens into the showplace of Greece. He appropriated Delian League funds to pay for a huge building program to rebuild the city that had been destroyed during the Persian occupation in 480 B.C.E., and to display to all Greeks the glory of the Athenian polis. Workers erected temples and other buildings as patriotic memorials housing statues and carvings, often painted in bright colors, showing the gods in human form and celebrating the Greek victory over the Persians. (The paint later washed away, leaving the generally white sculpture that we think of as “classical.”) Many of the temples were built on the high, rocky Acropolis that stood in the center of the city, on top of the remains of temples that had been burned by the Persians, and sometimes incorporating these into their walls.

The Athenians normally hiked up the long approach to the Acropolis only for religious festivals, of which the most important and joyous was the Great Panathenaea, held every four years to honor the virgin goddess Athena and perhaps offer sacrifices to older deities as well. (See “Evaluating the Evidence 3.2: The Acropolis of Athens.”) For this festival, Athenian citizens and legal noncitizen residents formed a huge procession to bring the statue of Athena in the Parthenon an exquisite robe, richly embroidered by the citizen women of Athens with mythological scenes. At the head of the procession walked an aristocratic young woman carrying an offering basket. She and other young unmarried women of the city had earlier left their toys and other marks of childhood in caves at the base of the Acropolis. Other richly dressed women followed her, most carrying gold and silver vessels containing wine and perfumes. Young men on horseback came next, followed by older men carrying staffs. Toward the rear came other young men carrying large pitchers of water and wine, or leading the bulls to the sacrifice. After the religious ceremonies, all the people joined in a feast.

Once the procession began, the marchers first saw the Propylaea, the ceremonial gateway whose columns appeared to uphold the sky. On the right was the small temple of Athena Nike, built to commemorate the victory over the Persians. The broad band of sculpture above its columns depicted the struggle between the Greeks and the Persians. To the left of the visitors stood the Erechtheum, a temple that housed several ancient shrines. On its southern side was the famous Portico of the Caryatids, a porch whose roof was supported by huge statues of young women. As visitors walked on, they obtained a full view of the Parthenon, the chief temple dedicated to Athena at the center of the Acropolis, with a huge painted ivory and gold statue of the goddess inside.

The development of drama was tied to the religious festivals of the city, especially those to the god of wine, Dionysus (see “Public and Personal Religion”). Drama was as rooted in the life of the polis as were the architecture and sculpture of the Acropolis. The polis sponsored the production of plays and required wealthy citizens to pay the expenses of their production. At the beginning of the year, dramatists submitted their plays to the chief archon of the polis. He chose those he considered best and assigned a theatrical troupe to each playwright. Many plays were highly controversial, containing overt political and social commentary, but the archons neither suppressed nor censored them.

Not surprisingly, given the incessant warfare, conflict was a constant element in Athenian drama, and playwrights used their art in attempts to portray, understand, and resolve life’s basic conflicts. The Athenian dramatists examined questions about the relationship between humans and the gods, the demands of society on the individual, and the nature of good and evil. Aeschylus (EHS-

Sophocles (SOFF-

With Euripides (your-

Writers of comedy treated the affairs of the polis and its politicians bawdily and often coarsely. Even so, their plays also were performed at religious festivals. Best known are the comedies of Aristophanes (eh-