A History of Western Society: Printed Page 220

A History of Western Society, Value Edition: Printed Page 206

A History of Western Society, Concise Edition: Printed Page 220

Chapter Chronology

The Prophet Muhammad

Except for a few vague remarks in the Qur’an (kuh-RAHN), the sacred book of Islam, Muhammad (ca. 571–632) left no account of his life. Arab tradition accepts some of the sacred stories that developed about him as historically true, but those accounts were not written down until about a century after his death. (Similarly, the earliest accounts of the life of Jesus, the Christian Gospels, were not written until forty to sixty years after his death.) Orphaned at the age of six, Muhammad was raised by his grandfather. As a young man he became a merchant in the caravan trade. Later he entered the service of a wealthy widow, and their subsequent marriage brought him financial independence.

The Qur’an reveals Muhammad to be an extremely devout man, ascetic, self-disciplined, and literate, but not formally educated. He prayed regularly, and when he was about forty he began to experience religious visions. Unsure for a time about what he should do, Muhammad discovered his mission after a vision in which the angel Gabriel instructed him to preach. Muhammad described his visions in a stylized and often rhyming prose and used this literary medium as his Qur’an, or “prayer recitation.” Muhammad’s revelations were written down by his followers during his lifetime and organized into chapters, called sura, shortly after his death. In 651 Muhammad’s third successor arranged to have an official version published. The Qur’an is regarded by Muslims as the direct words of God to his Prophet Muhammad and is therefore especially revered. (When Muslims around the world use translations of the Qur’an, they do so alongside the original Arabic, the language of Muhammad’s revelations.) At the same time, other sayings and accounts of Muhammad, which gave advice on matters that went beyond the Qur’an, were collected into books termed hadith (huh-DEETH). Muslim tradition (Sunna) consists of both the Qur’an and the hadith.

Muhammad’s visions ordered him to preach a message of a single God and to become God’s prophet, which he began to do in his hometown of Mecca. He gathered followers slowly, but also provoked a great deal of resistance because he urged people to give up worship of the gods whose sacred objects were in the Ka’ba and also challenged the power of the local elite. In 622 he migrated with his followers to Medina, an event termed the hijra (hih-JIGH-ruh) that marks the beginning of the Muslim calendar. At Medina Muhammad was much more successful, gaining converts and working out the basic principles of the faith. That same year, through the Charter of Medina, Muhammad formed the first umma, a community that united his followers from different tribes and set religious ties above clan loyalty. The charter also extended rights to non-Muslims living in Medina, including Jews and Christians, which set a precedent for the later treatment of Jews and Christians under Islam.

Page 221

In 630 Muhammad returned to Mecca at the head of a large army, and he soon united the nomads of the desert and the merchants of the cities into an even larger umma of Muslims, a word meaning “those who comply with God’s will.” The religion itself came to be called Islam, which means “submission to God.” The Ka’ba was rededicated as a Muslim holy place, and Mecca became the most holy city in Islam. According to Muslim tradition, the Ka’ba predates the creation of the world and represents the earthly counterpart of God’s heavenly throne, to which “pilgrims come dishevelled and dusty on every kind of camel.”1

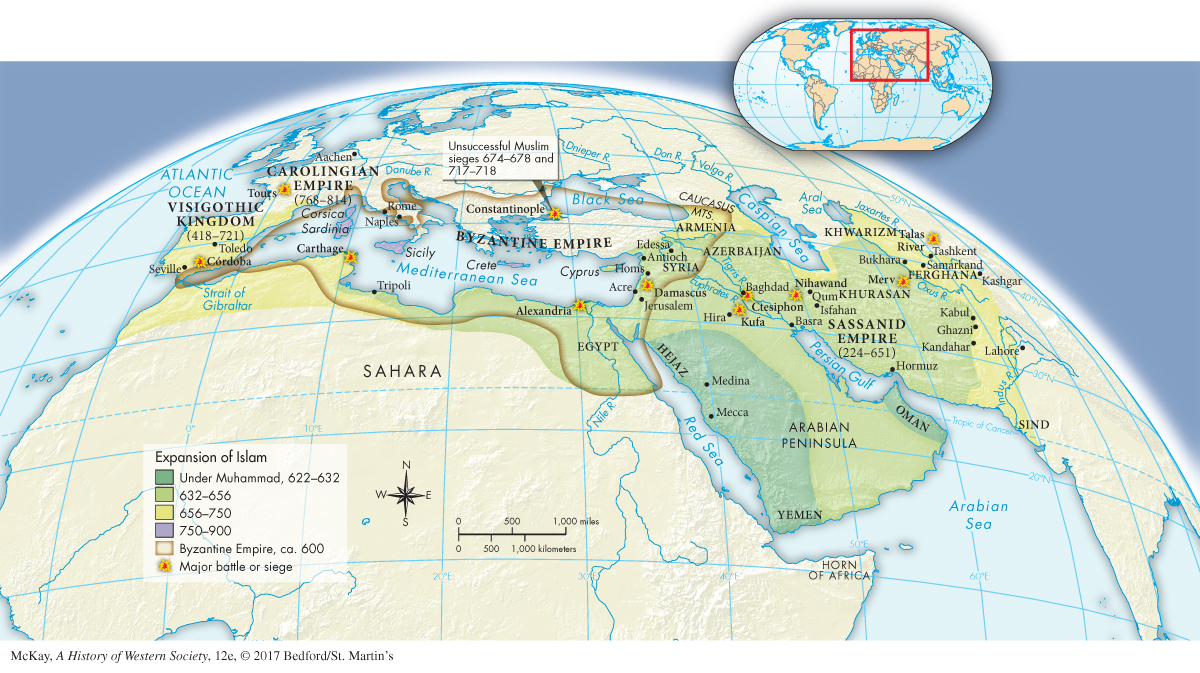

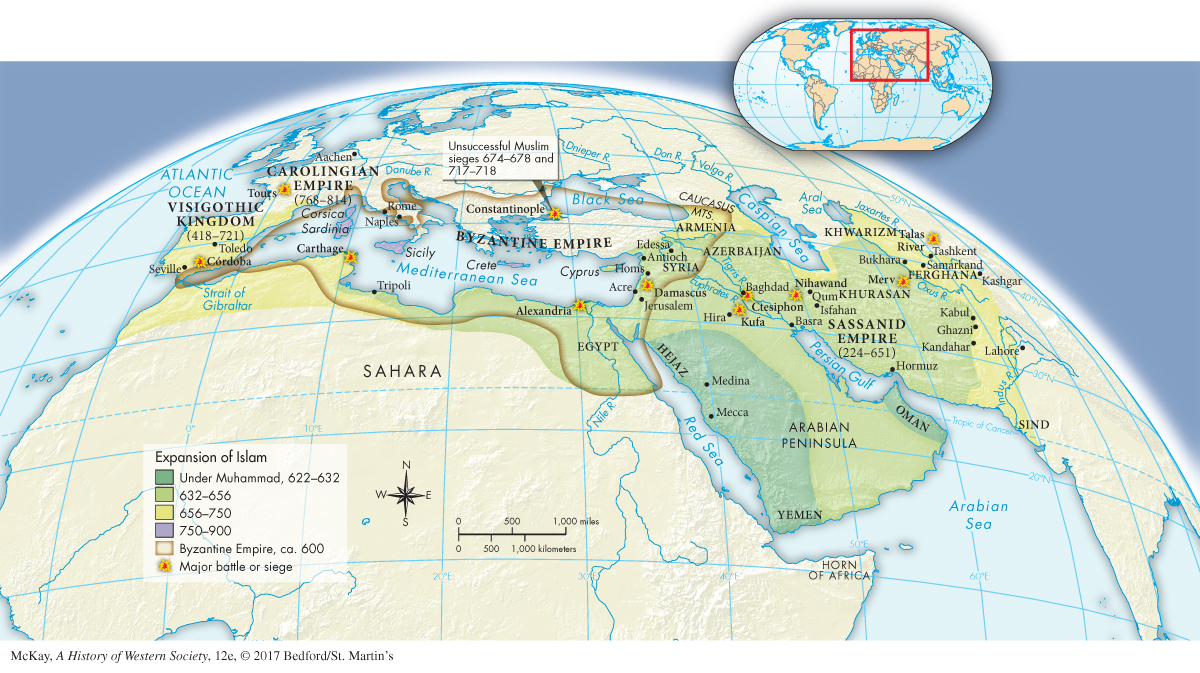

By the time Muhammad died in 632, the crescent of Islam, the Muslim symbol, prevailed throughout the Arabian peninsula. During the next century one rich province of the old Roman Empire after another came under Muslim domination — first Syria, then Egypt, and then all of North Africa (Map 8.1). Long and bitter wars (572–591, 606–630) between the Byzantine and Persian Empires left both so weak and exhausted that they easily fell to Muslim attack.

Figure 8.1: MAP 8.1 The Spread of Islam, 622–900 The rapid expansion of Islam in a relatively short span of time testifies to the Arabs’ superior fighting skills, religious zeal, and economic organization as well as to their enemies’ weakness.