A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 339

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 337

Chinggis’s Successors

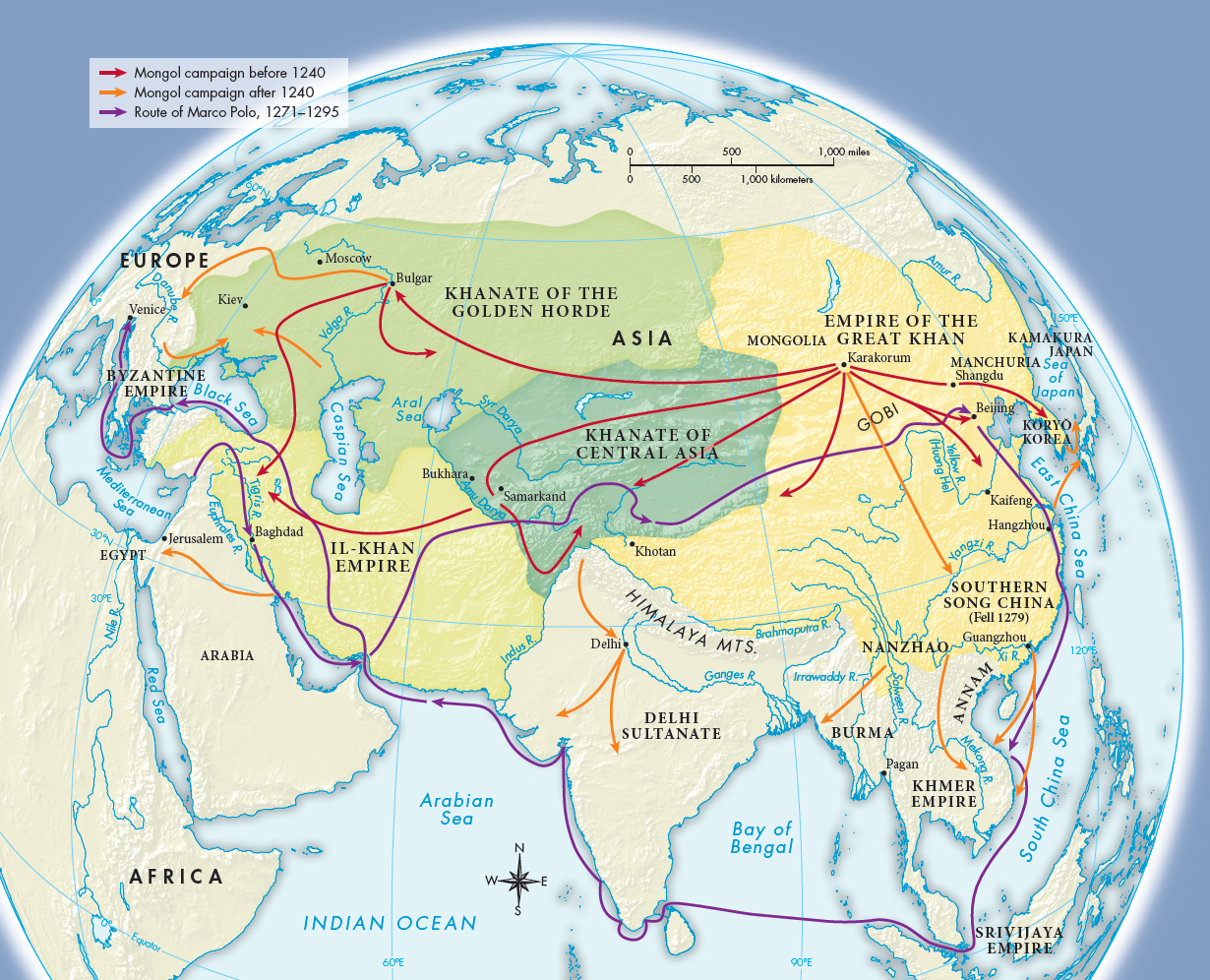

Although Mongol leaders traditionally had had to win their positions, after Chinggis died the empire was divided into four states called khanates, with one of the lines of his descendants taking charge of each (Map 12.1). Chinggis’s third son, Ögödei, assumed the title of khan, and he directed the next round of invasions.

In 1237 representatives of all four lines led 150,000 Mongol, Turkish, and Persian troops into Europe. During the next five years, they gained control of Moscow and Kievan Russia and looted cities in Poland and Hungary. They were poised to attack deeper into Europe when they learned of the death of Ögödei in 1241. To participate in the election of a new khan, the army returned to the Mongols’ new capital city, Karakorum.

Once Ögödei’s son was certified as his successor, the Mongols turned their attention to Persia and the Middle East. In 1256 a Mongol army took northwest Iran, then pushed on to the Abbasid capital of Baghdad. When it fell in 1258, the last Abbasid caliph was murdered, and the population was put to the sword. The Mongol onslaught was successfully resisted, however, by both the Delhi sultanate (see “The Delhi Sultanate”) and the Mamluk rulers in Egypt (see “The Mongol Invasions” in Chapter 9).

Under Chinggis’s grandson Khubilai Khan (r. 1260–

Having overrun China and Korea, Khubilai turned his eyes toward Japan. In 1274 a force of 30,000 soldiers and support personnel sailed from Korea to Japan. In 1281 a combined Mongol and Chinese fleet of about 150,000 made a second attempt to conquer Japan. On both occasions the Mongols managed to land but were beaten back by Japanese samurai armies. Each time fierce storms destroyed the Mongol fleets. The Japanese claimed that they had been saved by the kamikaze, the “divine wind” (which later lent its name to the thousands of Japanese aviators who crashed their airplanes into American warships during World War II). Twelve years later, in 1293, Khubilai tried sending a fleet to the islands of Southeast Asia, including Java, but it met with no more success than the fleets sent to Japan.

| 1206 | Temujin made Chinggis Khan |

| 1215 | Fall of Beijing (Jurchens) |

| 1219– |

Fall of Bukhara and Samarkand in Central Asia |

| 1227 | Death of Chinggis |

| 1237– |

Raids into eastern Europe |

| 1257 | Conquest of Annam (northern Vietnam) |

| 1258 | Conquest of Abbasid capital of Baghdad; conquest of Korea |

| 1260 | Khubilai succeeds to khanship |

| 1274 | First attempt at invading Japan |

| 1276 | Surrender of Song Dynasty (China) |

| 1281 | Second attempt at invading Japan |

| 1293 | Mongol fleet unsuccessful in invasion of Java |

| mid- |

Decline of Mongol power |

Why were the Mongols so successful against so many different types of enemies? Even though their population was tiny compared to the populations of the large agricultural societies they conquered, their tactics, their weapons, and their organization all gave them advantages. Like other nomads before them, they were superb horsemen and excellent archers. Their horses were extremely nimble, able to change direction quickly, thus allowing the Mongols to maneuver easily and ride through infantry forces armed with swords, lances, and javelins. Usually only other nomadic armies, like the Turks, could stand up well against the Mongols. (See “Viewpoints 12.1: Chinese and European Accounts About the Mongol Army.”)

The Mongols were also open to trying new military technologies. To attack walled cities, they learned how to use catapults and other engines of war. At first they employed Chinese catapults, but when they learned that those used by the Turks in Afghanistan were more powerful, they adopted the better model. The Mongols also used exploding arrows and gunpowder projectiles developed by the Chinese.

The Mongols made good use of intelligence and tried to exploit internal divisions in the countries they attacked. Thus in north China they appealed to the Khitans, who had been defeated by the Jurchens a century earlier, to join them in attacking the Jurchens. In Syria they exploited the resentment of Christians against their Muslim rulers.