A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 431

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 427

Chapter Chronology

Art and the Artist

No feature of the Renaissance evokes greater admiration than its artistic masterpieces. In Renaissance Italy wealthy merchants, bankers, popes, and princes spent vast sums to commission art as a means of glorifying themselves and their families. Patrons varied in their level of involvement as a work progressed; some simply ordered a specific subject or scene, while others oversaw the work of the artist or architect very closely, suggesting themes and styles and demanding changes while the work was in progress.

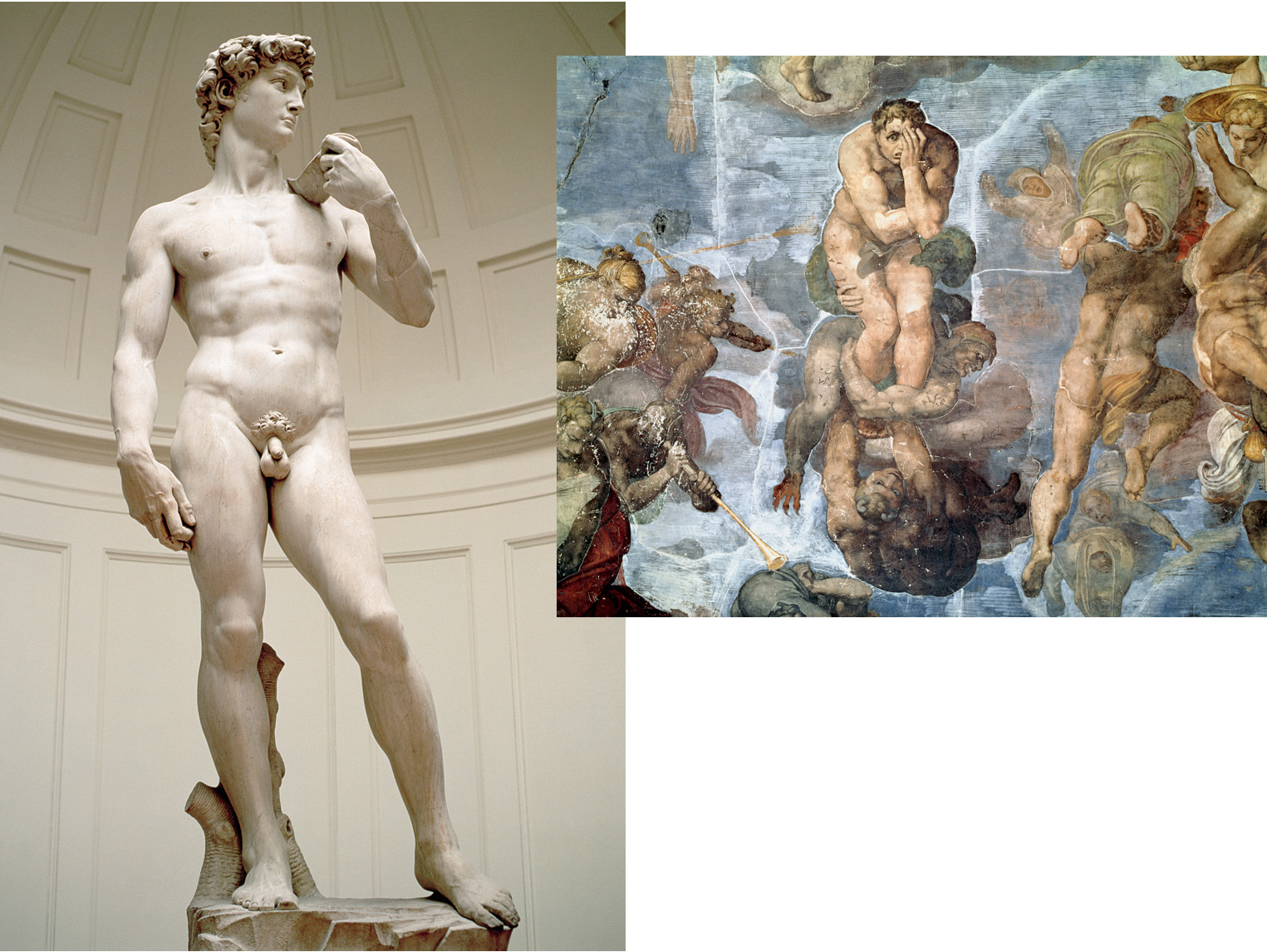

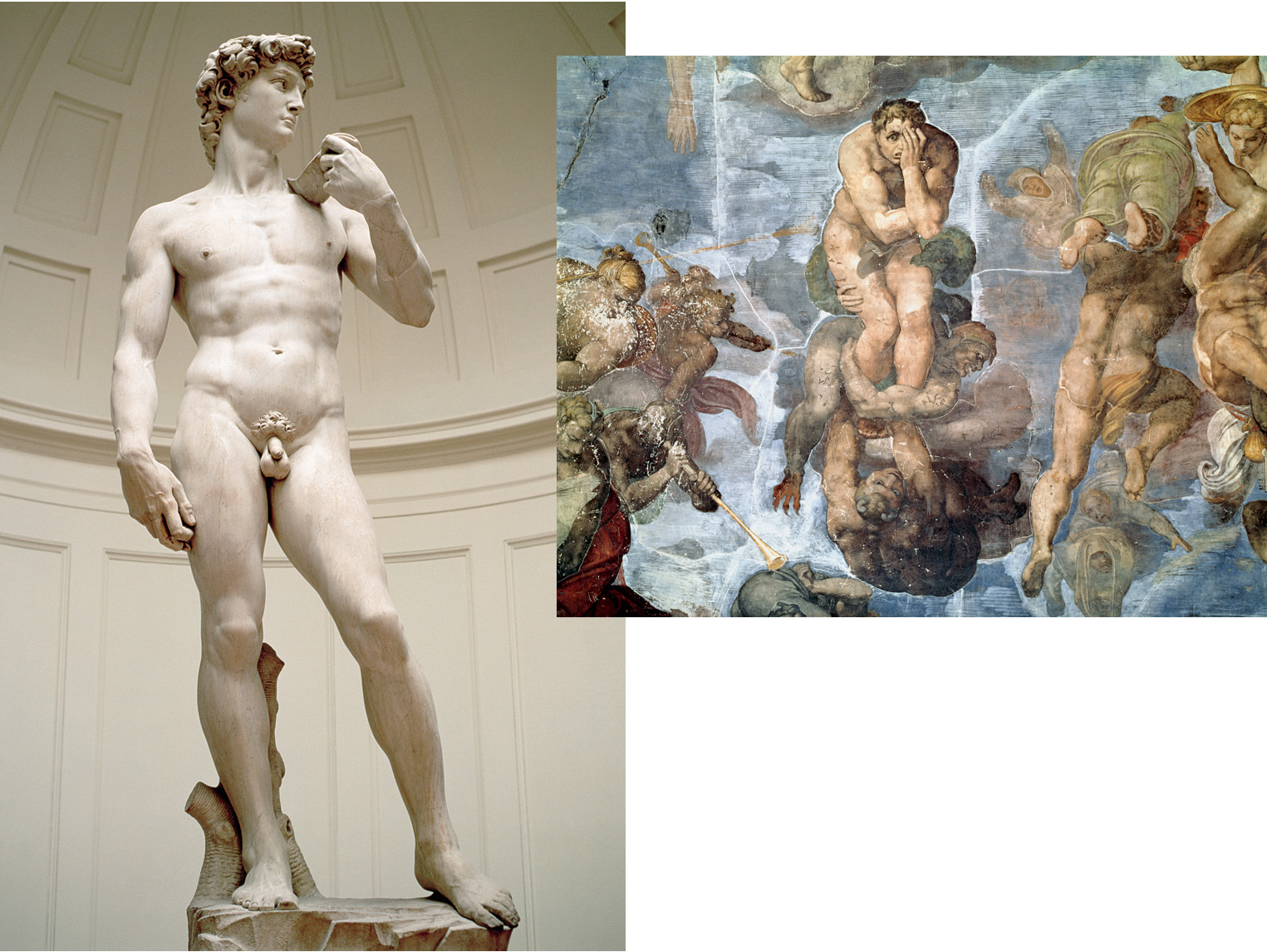

Michelangelo’s David (1501–1504) and the Last Judgment (detail, 1537–1541) Like all Renaissance artists, Michelangelo worked largely on commissions from patrons. Officials of the city of Florence contracted the young sculptor to produce a statue of the Old Testament hero David (left) to be displayed in the city’s main square. Michelangelo portrayed David anticipating his fight against the giant Goliath, and the statue came to symbolize the republic of Florence standing up to its larger and more powerful enemies. More than thirty years later, Michelangelo was commissioned by the pope to paint a scene of the Last Judgment on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel, where he had earlier spent four years covering the ceiling with magnificent frescoes. The massive work shows a powerful Christ standing in judgment, with souls ascending into Heaven while others are dragged by demons into Hell (above). The David captures ideals of human perfection and has come to be an iconic symbol of Renaissance artistic brilliance, while the dramatic and violent Last Judgment conveys both terror and divine power. (sculpture: Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence, Italy/Ken Welsh/The Bridgeman Art Library; painting: Vatican Museum and Galleries, Vatican City/Alinari/The Bridgeman Art Library)

As a result of patronage, certain artists gained great public acclaim and adulation, leading many historians to view the Renaissance as the beginning of the concept of the artist as genius. In the Middle Ages, people believed that only God created, albeit through individuals, and artistic originality was not particularly valued. By contrast, Renaissance artists and humanists came to think that a work of art was the deliberate creation of a unique personality, of an individual who transcended traditions, rules, and theories.

In terms of artistic themes, religious topics, such as the Annunciation of the Virgin Mary and the Nativity, remained popular among both patrons and artists, but frequently the patron had himself and his family portrayed in the scene. As the fifteenth century advanced and humanist ideas spread more widely, classical themes and motifs, such as the lives and loves of pagan gods and goddesses, figured increasingly in painting and sculpture, with the facial features of the gods sometimes modeled on those of living people. Classical styles also influenced architecture, as architects designed buildings that featured carefully proportioned arches and domes modeled on the structures of ancient Rome.

The individual portrait emerged as a distinct genre in Renaissance art. Rather than reflecting a spiritual ideal, as medieval painting and sculpture tended to do, Renaissance portraits showed human ideals, often portrayed in a more realistic style. The Florentine sculptor Donatello (1386–1466) revived the classical figure, with its balance and self-awareness. Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) was particularly adept at portraying female grace and beauty in his paintings of upper-class urban women and biblical figures such as the Virgin Mary. Another Florentine artist, Raphael Sanzio (1483–1520), painted hundreds of portraits and devotional images in his relatively short life, becoming the most sought-after artist in Europe (see “Introduction to Chapter 15”).

Donatello, Gattamelata, 1450 The Florentine sculptor Donatello’s bronze statue of the powerful military captain nicknamed Gattamelata (Honey-Cat) mounted on his horse was erected in the public square of Padua. The first bronze equestrian statue made since Roman times, the larger-than-life-size work seems to capture in metal the shrewd and determined type of ruler Machiavelli described in The Prince. (Scala/Art Resource, NY)

In the late fifteenth century the center of Renaissance art shifted from Florence to Rome, where wealthy cardinals and popes wanted visual expression of the church’s and their own families’ power and piety. To meet this demand, Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564) went to Rome from Florence in about 1500 and began the series of statues, paintings, and architectural projects from which he gained an international reputation. For example, he produced sculptures of Moses and of the Virgin Mary holding Jesus after his crucifixion (the Pietà), he redesigned the Capitoline Hill in central Rome, and most famously, between 1508 and 1512, he painted religiously themed frescoes on the ceiling and altar wall of the Sistine Chapel. Pope Julius II, who commissioned Michelangelo for the Sistine Chapel project, demanded that the artist work as fast as he could and frequently visited him to offer suggestions and criticism. Michelangelo complained in person and by letter about the pope’s meddling, but his fame did not match the power of the pope, and he kept working.

Though they might show individual genius, Renaissance artists were still expected to be schooled in proper artistic techniques and stylistic conventions, for the notion that artistic genius could show up in the work of the untrained did not emerge until the twentieth century. Therefore, in both Italy and northern Europe most aspiring artists were educated in the workshops of older artists. By the later sixteenth century formal academies were also established to train artists. Like universities, artistic workshops and academies were male-only settings in which students of different ages came together to learn and to create bonds of friendship, influence, patronage, and sometimes intimacy. Several women did become well known as painters during the Renaissance, but they were trained by their artist fathers and often quit painting when they married.

Women were not alone in being excluded from the institutions of Renaissance culture. Though a few talented artists such as Leonardo and Michelangelo emerged from artisanal backgrounds, most scholars and artists came from families with at least some money. The audience for artists’ work was also exclusive, limited mostly to educated and prosperous citizens. Although common people in large cities might have occasionally seen plays such as those of Shakespeare, most people lived in villages with no access to formal schooling or to the work of prominent artists. In general a small, highly educated minority of literary humanists and artists created the culture of and for a social elite. In this way the Renaissance maintained, and even enhanced, a gulf between the learned minority and the uneducated multitude that has survived for many centuries.

The Chess Game, 1555 In this oil painting, the Italian artist Sofonisba Anguissola (1532–1625) shows her three younger sisters playing chess, a game that was growing in popularity in the sixteenth century. Each sister looks at the one immediately older than herself, with the girl on the left looking out at her sister, the artist. Anguissola’s father, a minor nobleman, recognized his daughter’s talent and arranged for her to study with several painters. She became a court painter at the Spanish royal court, where she painted many portraits. Returning to Italy, she continued to be active, painting her last portrait when she was over eighty. (Museum Narodowe, Poznan, Poland/The Bridgeman Art Library)