A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 440

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 438

Martin Luther

By itself, widespread criticism of the church did not lead to the dramatic changes of the sixteenth century. Those resulted from the personal religious struggle of a German university professor, Martin Luther (1483–

Martin Luther was a very conscientious friar, but his scrupulous observance of the religious routine, frequent confessions, and fasting gave him only temporary relief from anxieties about sin and his ability to meet God’s demands. Through his study of Saint Paul’s letters in the New Testament, he gradually arrived at a new understanding of Christian doctrine. His understanding is often summarized as “faith alone, grace alone, scripture alone.” He believed that salvation and justification (righteousness in God’s eyes) come through faith, and that faith is a free gift of God, not the result of human effort. God’s word is revealed only in biblical scripture, not in the traditions of the church.

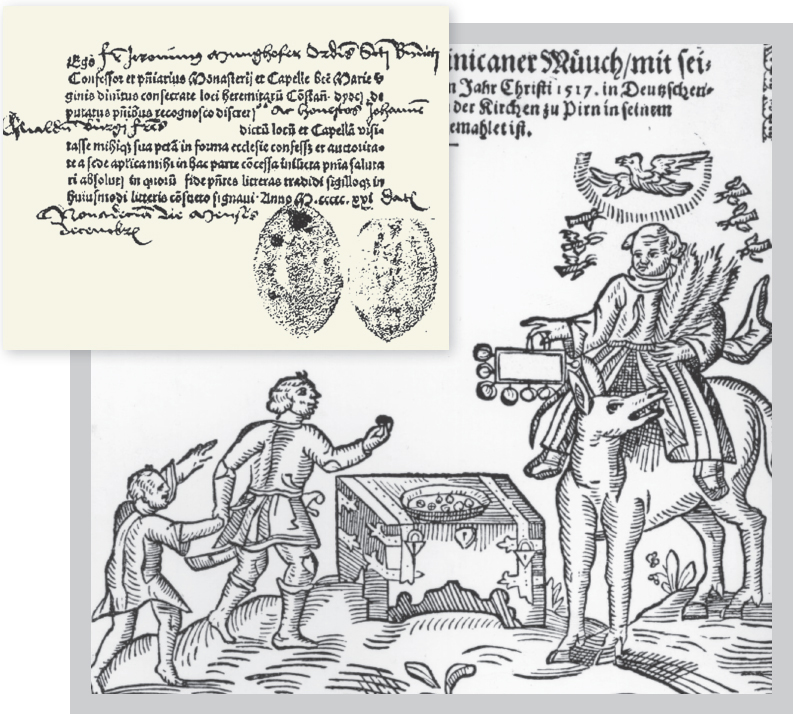

At the same time that Luther was engaged in scholarly reflections and professorial lecturing, Pope Leo X authorized a special Saint Peter’s indulgence to finance his building plans in Rome. An indulgence was a document, signed by the pope or another church official, that substituted for penance. The archbishop who controlled the area in which Wittenberg was located, Albert of Mainz, also promoted the sale of indulgences, in his case to pay off a debt he had incurred to be named bishop of several additional territories. Albert’s sales campaign, run by a Dominican friar who mounted an advertising blitz, promised that the purchase of indulgences would bring full forgiveness for one’s own sins or buy release from purgatory for a loved one. One of the slogans — “As soon as coin in coffer rings, the soul from purgatory springs” — brought phenomenal success.

Luther was severely troubled that many people believed that they had no further need for repentance once they had purchased indulgences. He wrote a letter to Archbishop Albert on the subject and enclosed in Latin his “Ninety-

Unless I am convinced by the evidence of Scripture or by plain reason — for I do not accept the authority of the Pope or the councils alone, since it is established that they have often erred and contradicted themselves — I am bound by the Scriptures I have cited and my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and will not recant anything, for it is neither safe nor right to go against conscience.4