A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 506

Listening to the Past

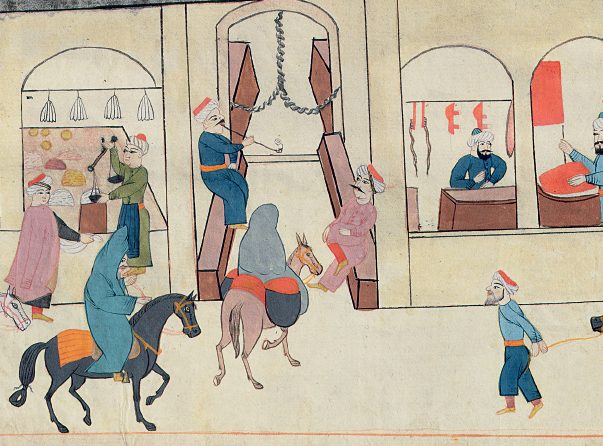

Katib Chelebi on Tobacco

Listening to the Past

Katib Chelebi on Tobacco

Katib Chelebi (1609–

Katib Chelebi, “The Balance of Truth”

“When the year 800 after the Hijra approached the year 900 [in the fifteenth century], and when Spanish ships found the New World. The Portuguese and the English were also sailing through the shores in order to pass from the Western seas to the Eastern seas, they arrived at an island,* which is close to the shores noted as Gineya in the Atlas. Due to the negative impact of the humidity of the sea air on his nature, a doctor from the crew of the ship suffered from what appeared to be a lymphatic disorder. While he was looking for a cure, employing hot and dry things in accordance with the dictum “Cure is in the opposite,” his ship arrived at the aforementioned island, and he saw that some sort of a leaf was burning. Smelling its scent, he understood that it was a hot scent, and he started sucking the smoke through a pipe-

It appeared around 1010 A.H. [1601]. Since then various preachers mentioned it, and many learned men wrote treatises; some argued that it is religiously prohibited, and others disapproved. Those who were addicted, on the other hand, replied to these with their own treatises. After a while, in the court of the sultan [that is, in Istanbul], Şeyhi Ibrahim Efendi, the surgeon of the Palace, showed extreme care for the topic and talked about it at length and preached in the public seminar of Sultan Mehemmed Mosque and hung on the wall copies of the counsel and religious opinion [fatwa] in vain. As he talked about it, people smoked more and became more obstinate. Seeing it doesn’t help, he gave in.

Later, towards the end of his reign, Sultan Murad IV [1612–

The first argument is that people can be prevented through prohibition and can quit tobacco. Since habit is second nature, we need to push aside this possibility. Addicts cannot be made to quit this way. . . .

The second discussion concerns the question of whether tobacco is good or bad with respect to reason. We can neglect the approval of it by addicts, and the intelligent accepted it as bad; either the judgment of good or bad have to be determined by both reason and religious law. . . .

The third argument is about its benefits and harmful effects. There is no doubt that it is financially harmful. However, since it becomes one of the most essential items for the addict, he doesn’t mind its financial harm. Its harm on the body is well attested. Since tobacco pollutes the essence of air breathed by people, it is physically harmful.

The fourth argument is whether or not it is an innovation according to religion. It is an innovation according to the religious law, since it appeared in recent times. Moreover, it cannot be argued that it is an acceptable innovation. It is also rationally an innovation, because smoking hasn’t been seen or heard of by the intelligent since the time of Adam. . . .

The fifth argument concerns if it is religiously abominable or not. There is no way to deny that it is abominable in reason and in religion; everyone has accepted this argument. Since the scent of tobacco smoke and the scent of its leaves are not abominable in themselves, for it to be accepted as abominable, its excessive use is a condition.† . . .

The sixth argument is about its being unlawful or not. To produce a judgment on a topic through independent reasoning is accepted as a method in books of religious law. There are sufficient conditions collected to proscribe tobacco through an analysis of available proof. Yet it is preferable not to proclaim it forbidden. It is recommended to accept it as religiously permissible in order to protect people from insisting on sin by doing forbidden acts through the application of a legal principle.

The seventh argument is whether or not it is religiously permissible. Since tobacco appeared in recent times, it is not clearly considered and mentioned in books of religious law. Consequently, following the dictum, “In things permissibility is inherent,” smoking is considered as permissible and legitimate.”

Source: Mecmu’a-

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

- What do you learn about social life in the Ottoman Empire from this essay?

- What can you infer about the sorts of arguments that were made by Islamic jurists in Katib Chelebi’s day?

- How open-

minded was Katib Chelebi? What evidence from the text led you to your conclusion?