A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 773

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 783

Chapter Chronology

Egypt: From Reform to British Occupation

The ancient land of the pharaohs had been ruled by a succession of foreigners from 525 B.C.E. to the Ottoman conquest in the early sixteenth century. In 1798, as France and Britain prepared for war in Europe, the young French general Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Egypt, thereby threatening British access to India, and occupied the territory for three years. Into the power vacuum left by the French withdrawal stepped an extraordinary Albanian-born Turkish general, Muhammad Ali (1769–1849).

Appointed Egypt’s governor by Sultan Salim III in 1805, Muhammad Ali set out to build his own state on the strength of a large, powerful army organized along European lines. In 1820–1822 the Egyptian leader conquered much of the Sudan to secure slaves for his army, the first of thousands of African slaves brought to Egypt during his reign. Because many slaves died in Egyptian captivity, Muhammad Ali turned to drafting Egyptian peasants. He also reformed the government and promoted modern industry. (See “Individuals in Society: Muhammad Ali.”) For a time Muhammad Ali’s ambitious strategy seemed to work, but it eventually foundered when his armies occupied Syria and he threatened the Ottoman sultan, Mahmud II. In the face of European military might and diplomatic entreaties, Muhammad Ali agreed to peace with his Ottoman overlords and withdrew. In return he was given unprecedented hereditary rule over Egypt and Sudan. By his death in 1849, Muhammad Ali had established a strong and virtually independent Egyptian state within the Ottoman Empire.

To pay for a modern army and industrialization, Muhammad Ali encouraged the development of commercial agriculture geared to the European market, which had profound social implications. Egyptian peasants had been poor but largely self-sufficient, growing food on state-owned land allotted to them by tradition. Offered the possibility of profits from export agriculture, high-ranking officials and members of Muhammad Ali’s family began carving large private landholdings out of the state domain, and they forced the peasants to grow cash crops for European markets. Landownership became very unequal. By 1913, 12,600 large estates owned 44 percent of the land, and 1.4 million peasants owned only 27 percent. Estate owners also “modernized” agriculture, to the detriment of the peasants’ well-being.

Muhammad Ali’s modernization policies attracted growing numbers of Europeans to the banks of the Nile. In 1863, when Muhammad Ali’s grandson Ismail began his sixteen-year rule as Egypt’s khedive (kuh-DEEV), or prince, the port city of Alexandria had more than fifty thousand Europeans. By 1900 about two hundred thousand Europeans lived in Egypt, accounting for 2 percent of the population. Europeans served as army officers, engineers, doctors, government officials, and police officers. Others worked in trade, finance, and shipping. Above all, Europeans living in Egypt combined with landlords and officials to continue steering commercial agriculture toward exports. As throughout the Ottoman Empire, Europeans enjoyed important commercial and legal privileges and formed an economic elite.

The Suez Canal, 1869

Ismail (r. 1863–1879) was a westernizing autocrat. Educated at France’s leading military academy, he dreamed of using European technology and capital to modernize Egypt and build a vast empire in northeastern Africa. He promoted cotton production, and exports to Europe soared. Ismail also borrowed large sums, and with his support the Suez Canal was completed by a French company in 1869, shortening the voyage from Europe to Asia by thousands of miles. Cairo acquired modern boulevards and Western hotels. As Ismail proudly declared, “My country is no longer in Africa, we now form part of Europe.”11

Major cultural and intellectual changes accompanied the political and economic ones. The Arabic of the masses, rather than the conqueror’s Turkish, became the official language, and young, European-educated Egyptians helped spread new skills and ideas in the bureaucracy. A host of writers, intellectuals, and religious thinkers responded to the novel conditions with innovative ideas that had a powerful impact in Egypt and other Muslim societies.

Three influential figures who represented broad families of thought were especially significant. The teacher and writer Jamal al-Din al-Afghani (1838/39–1897) preached Islamic regeneration and defense against Western Christian aggression. Regeneration, he argued, required the purification of religious belief, Muslim unity, and a revolutionary overthrow of corrupt Muslim rulers and foreign exploiters. The more moderate Muhammad Abduh (1849–1905) also sought Muslim rejuvenation and launched the modern Islamic reform movement, which became very important in the twentieth century. Abduh concluded that Muslims should adopt a flexible, reasoned approach to change, modernity, science, social questions, and foreign ideas and not reject these out of hand.

Finally, the writer Qasim Amin (1863–1908) represented those who found inspiration in the West in the late nineteenth century. In his influential book The Liberation of Women (1899), Amin argued forcefully that superior education for European women had contributed greatly to the Islamic world’s falling far behind the West. The rejuvenation of Muslim societies required greater equality for women:

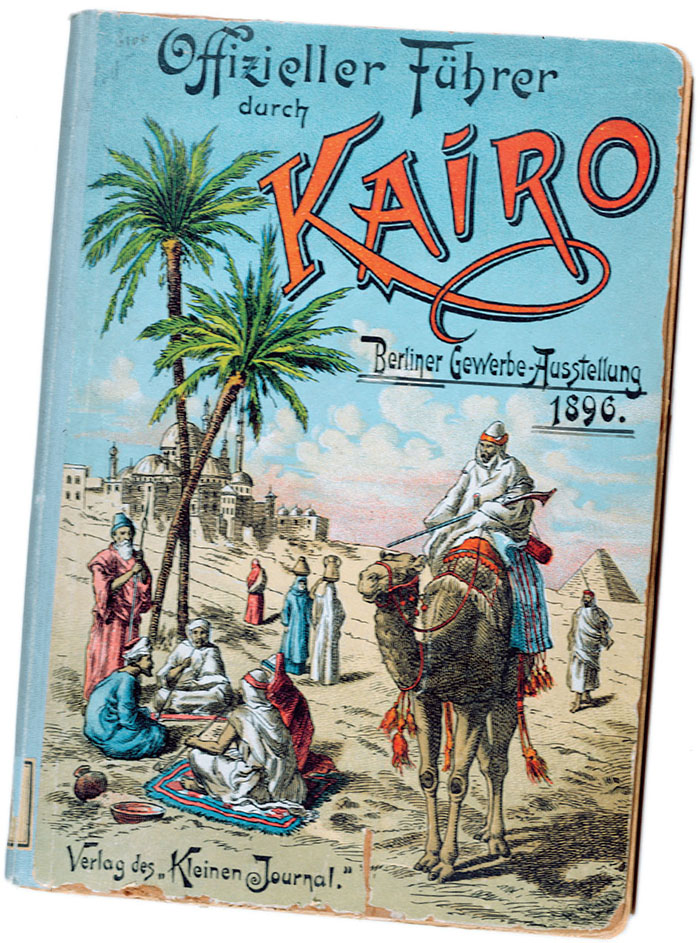

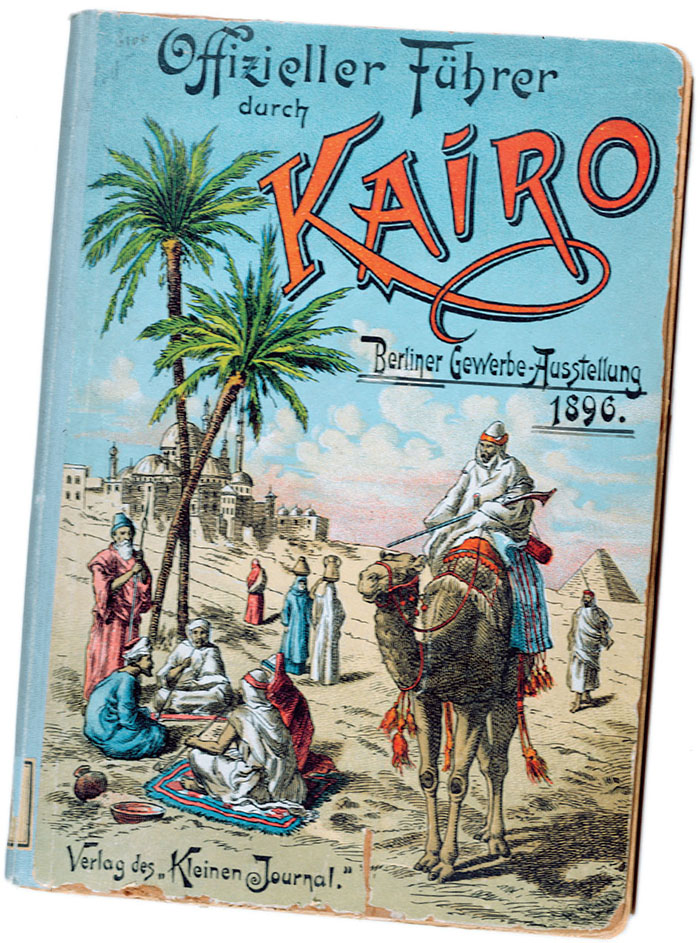

Egyptian Travel Guide Ismail’s efforts to transform Cairo were fairly successful. As a result, European tourists could more easily visit the country that their governments dominated. Ordinary Europeans were lured to exotic lands by travel books like this colorful “Official Guide” to an exhibition on Cairo held in Berlin. (Private Collection/Archives Charmet/The Bridgeman Art Library)

History confirms and demonstrates that the status of women is inseparably tied to the status of a nation. Where the status of a nation is low, reflecting an uncivilized condition for that nation, the status of women is also low, and when the status of a nation is elevated, reflecting the progress and civilization of that nation, the status of women in that country is also elevated.12

Egypt changed rapidly during Ismail’s rule, but his projects were reckless and enormously expensive. By 1876 the government could not pay the interest on its colossal debt. Rather than let Egypt go bankrupt and repudiate its loans, France and Great Britain intervened politically to protect the European investors who held the Egyptian bonds. To guarantee the Egyptian debt would be paid in full, they forced Ismail to appoint French and British commissioners to oversee Egyptian finances. This meant that Europeans would determine the state budget and in effect rule Egypt.

Foreign financial control evoked a violent nationalistic reaction among Egyptian religious leaders, intellectuals, and army officers. In 1879 they formed the Egyptian Nationalist Party with Colonel Ahmed Arabi as their leader. Continuing diplomatic pressure, which forced Ismail to abdicate in favor of his weak son, Tewfiq (r. 1879–1892), resulted in bloody anti-European riots in Alexandria in 1882. Several Europeans were killed, and Tewfiq and his court had to seek refuge on British ships. The British fleet then bombarded Alexandria, and a British expeditionary force decimated Arabi’s forces and occupied all of Egypt. British armies remained in Egypt until 1956.

Initially the British maintained the façade of the khedive’s government as an autonomous province of the Ottoman Empire, but the khedive was a mere puppet. The British consul, General Evelyn Baring, later Lord Cromer, ruled the country after 1883. Baring was a paternalistic reformer. He initiated tax reforms and made some improvements to conditions for peasants. Foreign bondholders received their interest payments, while Egyptian nationalists chafed under foreign rule.