A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 760

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 771

Chapter Chronology

Southern Africa in the Nineteenth Century

The development of southern Africa diverged from the rest of sub-Saharan Africa in important ways. Whites settled in large numbers, modern capitalist industry took off, and British imperialists had to wage all-out war.

In 1652 the Dutch East India Company established a supply station at Cape Town for Dutch ships sailing between Amsterdam and Indonesia. The healthy, temperate climate and the sparse Khoisan population near the Cape promoted the colony’s gradual expansion. When the British took possession of the Cape Colony during the Napoleonic Wars, there were about twenty thousand free Dutch citizens and twenty-five thousand African slaves, with substantial mixed-race communities on the northern frontier of white settlement. After 1815 powerful African chiefdoms, Dutch settlers — first known as Boers, and then as Afrikaners — and British colonial forces waged a complicated three-cornered battle to build strong states in southern Africa.

While the British consolidated their rule in the Cape Colony, the talented Zulu king Shaka (r. 1818–1828) was revolutionizing African warfare and creating the largest and most powerful kingdom in southern Africa in the nineteenth century. Drafted by age groups and placed in highly disciplined regiments, Shaka’s warriors perfected the use of a short stabbing spear in deadly hand-to-hand combat. The Zulu armies often destroyed their African enemies completely, sowing chaos and sending refugees fleeing in all directions. Shaka’s wars led to the creation of Zulu, Tswana, Swazi, Ndebele, and Sotho states in southern Africa. By 1890 these states were largely subdued by Dutch and British invaders, but only after many hard-fought frontier wars.

Between 1834 and 1838 the British abolished slavery in the Cape Colony and introduced color-blind legislation (whites and blacks were equal before the law) to protect African labor. In 1836 about ten thousand Afrikaner cattle ranchers and farmers, resentful of equal treatment of blacks by British colonial officials and missionaries after the abolition of slavery, began to make their so-called Great Trek northward into the interior. In 1845 another group of Afrikaners joined them north of the Orange River. Over the next thirty years Afrikaner and British settlers, who often fought and generally detested each other, reached a mutually advantageous division of southern Africa. The British ruled the strategically valuable colonies of Cape Colony and Natal (nuh-TAL) on the coast, and the Afrikaners controlled the ranch-land republics of Orange Free State and the Transvaal in the interior. The Zulu, Xhosa, Sotho, Ndebele, and other African peoples lost much of their land but remained the majority — albeit an exploited majority.

The discovery of incredibly rich deposits of diamonds in 1867 near Kimberley, and of gold in 1886 in the Afrikaners’ Transvaal Republic around modern Johannesburg, revolutionized the southern African economy, making possible large-scale industrial capitalism and transforming the lives of all its peoples. The extraction of these minerals, particularly the deep-level gold deposits, required big foreign investment, European engineering expertise, and an enormous labor force. Thus small-scale white and black diamond and gold miners soon gave way to powerful financiers, particularly Cecil Rhodes (1853–1902). Rhodes came from a large middle-class British family and at seventeen went to southern Africa to seek his fortune. By 1888 Rhodes’s firm, the De Beers mining company, monopolized the world’s diamond industry and earned him fabulous profits. The “color bar” system of the diamond fields gave whites — often English-speaking immigrants — the well-paid skilled positions and put black Africans in the dangerous, low-wage jobs far below the earth’s surface. Whites lived with their families in subsidized housing. African workers lived in all-male prison-like dormitories, closely watched by company guards. Southern Africa became the world’s leading gold producer, pulling in black migratory workers from all over the region (as it does to this day).

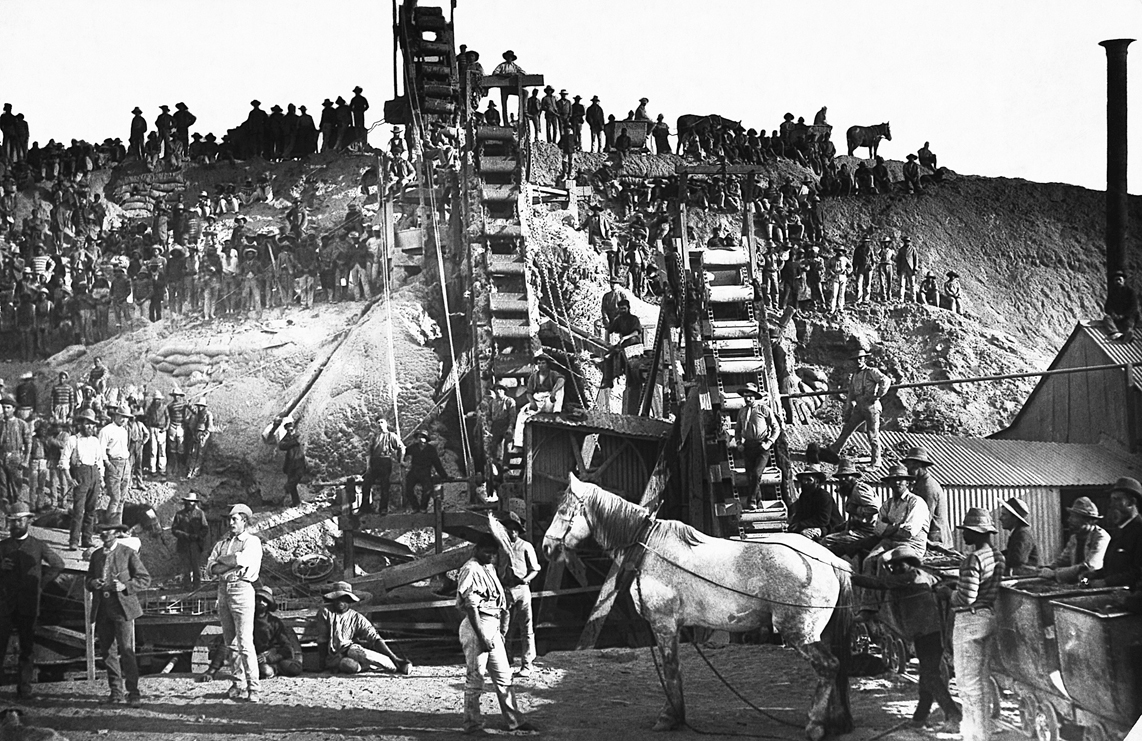

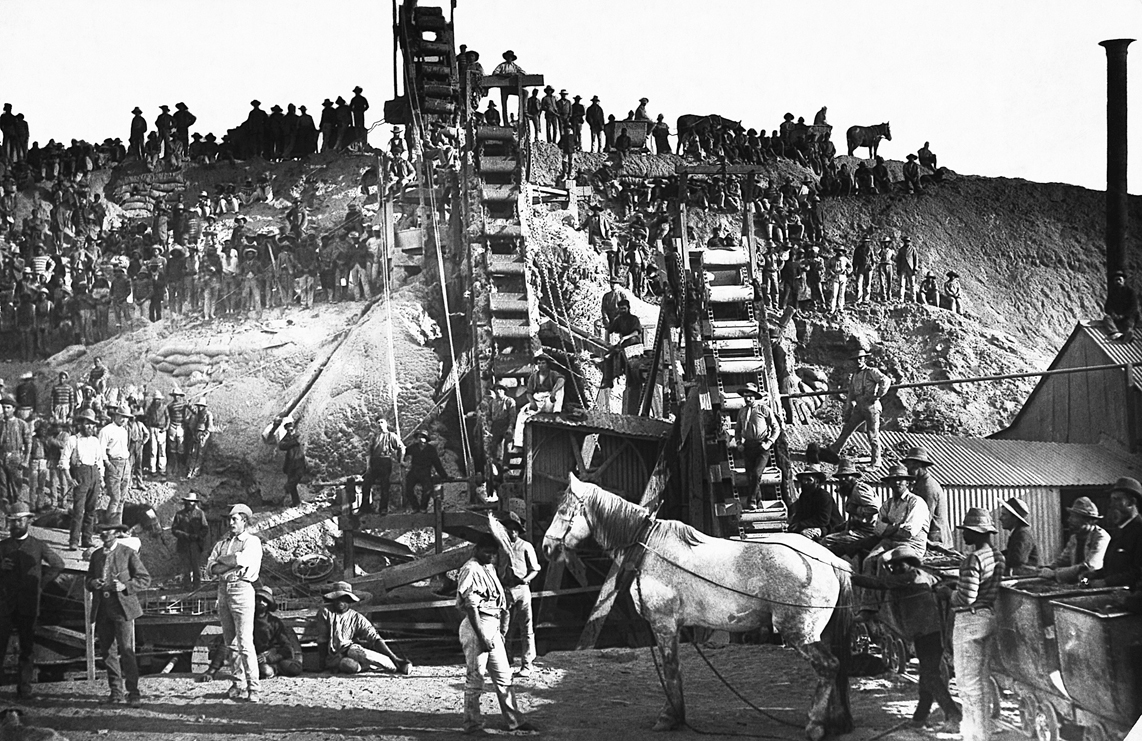

Diamond Mining in South Africa At first, both black and white miners could own and work claims at the diamond diggings, as this early photo suggests. However, as the industry expanded and was monopolized by European financial interests, white workers claimed the supervisory jobs, and blacks were limited to dangerous low-wage labor. (Robert Harvey/© Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis)

The mining bonanza whetted the appetite of British imperialists led by the powerful Rhodes, who was considered the ultimate British imperialist. He once famously observed that the British “happen to be the best people in the world, with the highest ideals of decency and justice and liberty and peace, and the more of the world we inhabit, the better for humanity.”7 Between 1888 and 1893 Rhodes used missionaries and his British South Africa Company, chartered by the British government, to force African chiefs to accept British protectorates, and he managed to add Southern and Northern Rhodesia (modern-day Zimbabwe and Zambia) to the British Empire.

Southern Rhodesia is one of the most egregious examples of Europeans misleading African rulers to take their land. In 1888 the Ndebele (or Matabele) king, Lobengula (1845–1894), ruler over much of modern southwestern Zimbabwe, met with three of Rhodes’s men, led by Charles Rudd, and signed the Rudd Concession. Lobengula believed he was simply allowing a handful of British fortune hunters a few years of gold prospecting in Matabeleland. Lobengula had been misled, however, by the resident London Missionary Society missionary (and Lobengula’s supposed friend), the Reverend Charles Helm, as to the document’s true meaning and Rhodes’s hand behind it. Even though Lobengula soon repudiated the agreement, he opened the way for Rhodes’s seizure of the territory. (See “Viewpoints 25.2: African Views of the Scramble for Africa.”)

The Struggle for South Africa, 1878

In 1889 Rhodes’s British South Africa Company received a royal charter from Queen Victoria to occupy the land on behalf of the British government. Though Lobengula died in early 1894, his warriors fought Rhodes’s private army in the First and Second Matabele Wars (1893–1894, 1896–1897); however, they were decimated by British Maxim guns. By 1897 Matabeleland had ceased to exist, replaced by the British-ruled settler colony of Southern Rhodesia. Before his death, Lobengula asked Reverend Helm, “Did you ever see a chameleon catch a fly? The chameleon gets behind the fly and remains motionless for some time, then he advances very slowly and gently, first putting forward one leg and then the other. At last, when well within reach, he darts his tongue and the fly disappears. England is the chameleon and I am that fly.”8

The Transvaal goldfields still remained in Afrikaner hands, however, so Rhodes and the imperialist clique initiated a series of events that sparked the South African War of 1899–1902 (also known as the Anglo-Boer War), Britain’s greatest imperial campaign on African soil. The British needed 450,000 troops to crush the Afrikaners, who never had more than 30,000 men in the field. Often considered the first “total war,” this conflict witnessed the British use of a scorched-earth strategy to destroy Afrikaner property, and concentration camps to detain Afrikaner families and their servants, thousands of whom died of illness. Estimates of Africans who were sometimes forced and sometimes volunteered to work for one side or the other range from 15,000 to 40,000 for each side. They did everything from scouting and guard duty to heavy manual labor, driving wagons, and guarding the livestock.

The long and bitter war divided whites in South Africa, but South Africa’s blacks were the biggest losers. The British had promised the Afrikaners representative government in return for surrender in 1902, and they made good on their pledge. In 1910 the Cape Colony, Natal, the Orange Free State, and the Transvaal formed a new self-governing Union of South Africa. After the peace settlement, because whites — 21.5 percent of the total population in 1910 — held almost all political power in the new union, and because Afrikaners outnumbered English-speakers, the Afrikaners began to regain what they had lost on the battlefield. South Africa, under a joint British-Afrikaner government within the British Empire, began the creation of a modern segregated society that culminated in an even harsher system of racial separation, or apartheid, after World War II.