A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 799

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 808

Chapter Chronology

China’s humiliating defeat in the Sino-Japanese War in 1895 led to a renewed drive for reform. In 1898 a group of educated young reformers gained access to the twenty-seven-year-old Qing emperor. They warned him of the fate of Poland (divided by the European powers in the eighteenth century; see “Enlightened Absolutism and its Limits” in Chapter 19) and regaled him with the triumphs of the Meiji reformers in Japan. They proposed redesigning China as a constitutional monarchy with modern financial and educational systems. For three months the emperor issued a series of reform decrees. But the Manchu establishment and the empress dowager, who had dominated the court for the last quarter century, felt threatened and not only suppressed the reform movement but imprisoned the emperor as well. Hope for reform from the top was dashed.

A period of violent reaction swept the country, reaching its peak in 1900 with the uprising of a secret society that foreigners dubbed the Boxers. The Boxers blamed China’s ills on foreigners, especially the missionaries who traveled throughout China telling the Chinese that their beliefs were wrong and their customs backward. After the Boxers laid siege to the foreign legation quarter in Beijing, a dozen nations including Japan sent twenty thousand troops to lift the siege. In the negotiations that followed, China had to accept a long list of penalties, including cancellation of the civil service examinations for five years (punishment for gentry collaboration) and a staggering indemnity of 450 million ounces of silver, almost twice the government’s annual revenues.

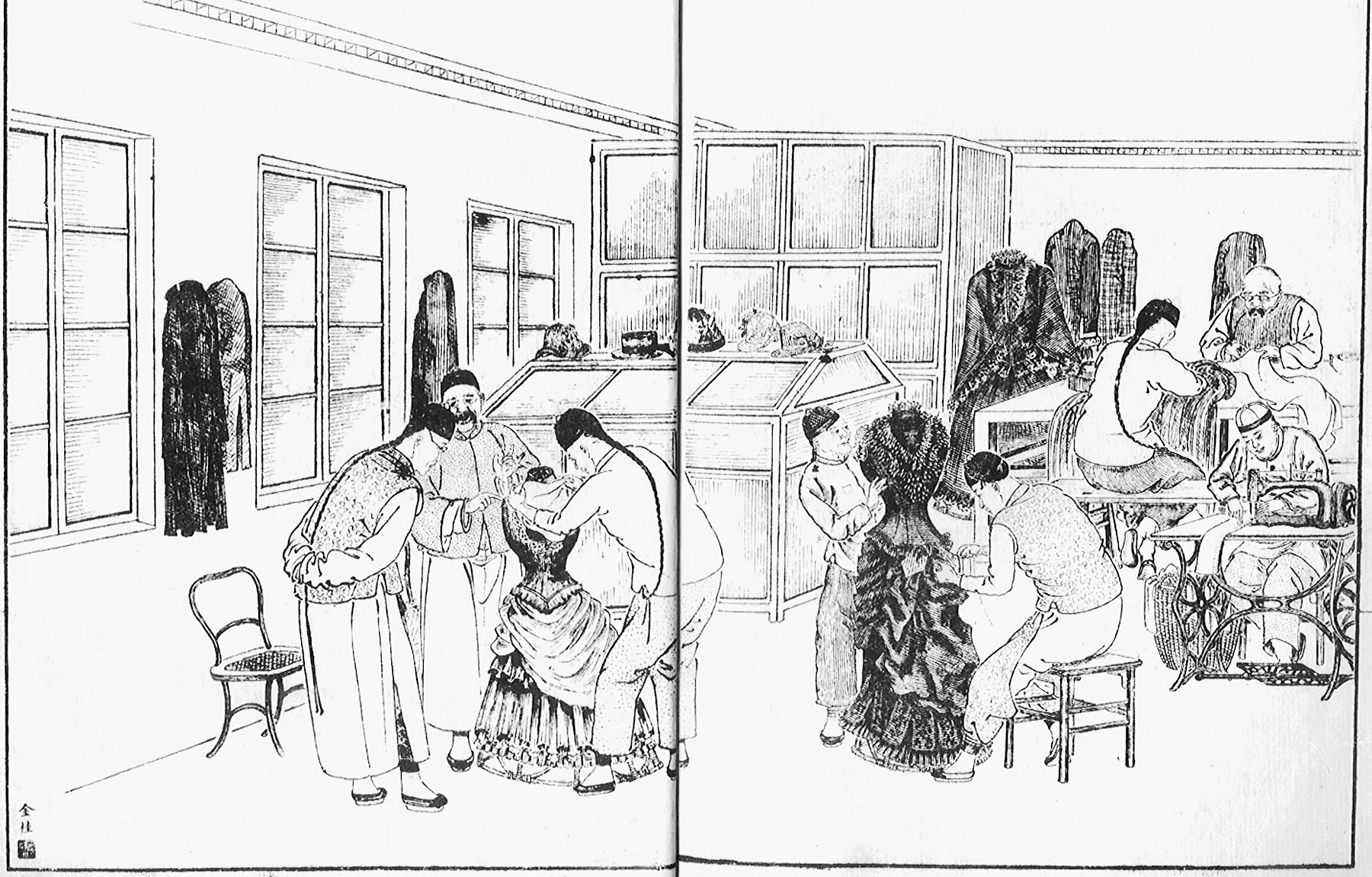

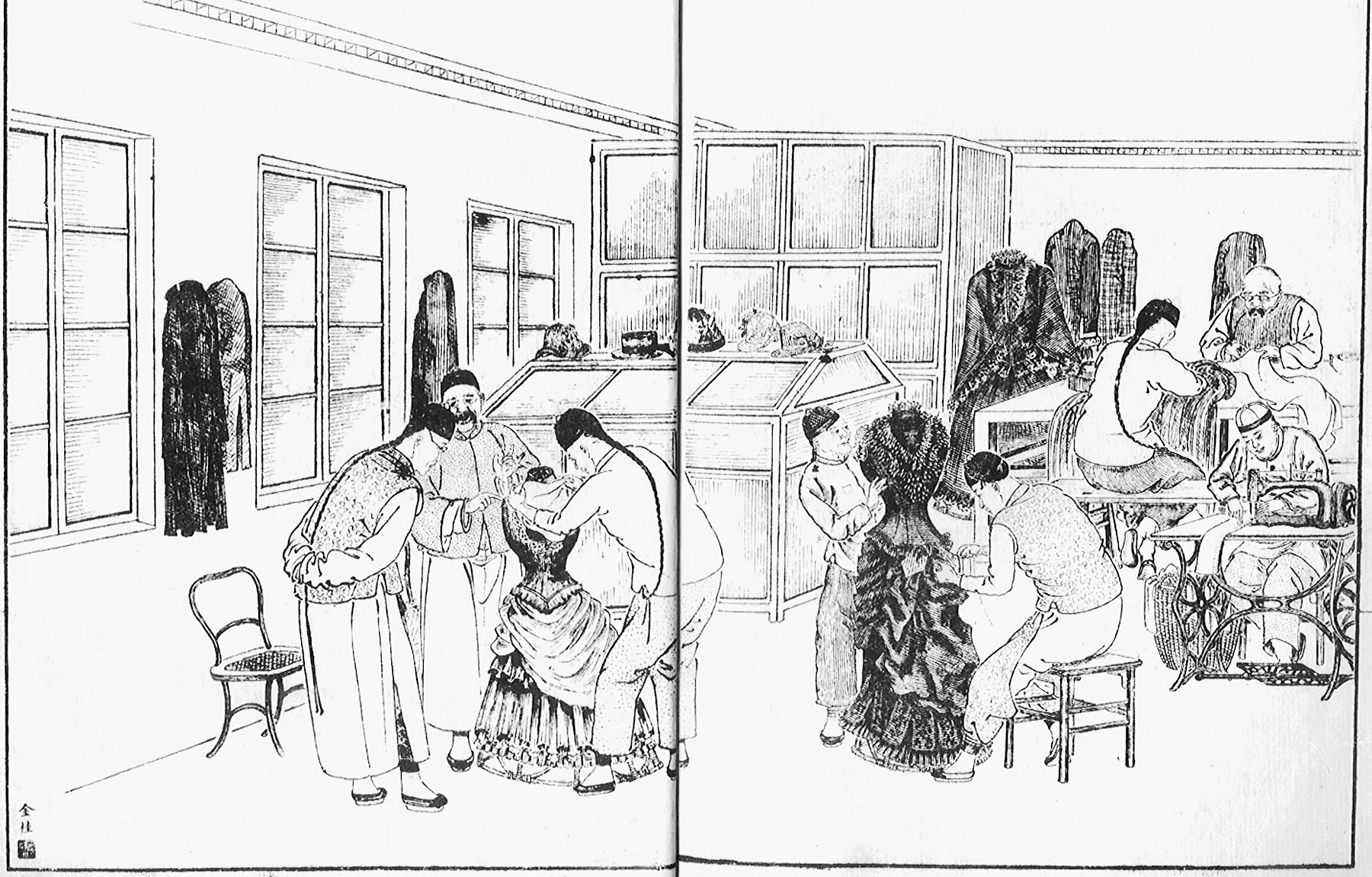

Hong Kong Tailors In 1872 the newspaper Shenbao was founded in Shanghai, and in 1884 it added an eight-page weekly pictorial supplement. Influenced by the pictorial press then popular in Europe, it depicted both news and human interest stories, both Chinese and foreign. This scene shows a tailor shop in Hong Kong where Chinese tailors use sewing machines and make women’s clothes in current Western styles. To Chinese readers, men making women’s clothes and placing them on bamboo forms would have seemed as peculiar as the style of the dresses. (From Dianshizhai huabao, a Shanghai picture magazine, 1885 or later/Visual Connection Archive)

After this defeat, gradual reform lost its appeal. More and more Chinese were studying abroad and learning about Western political ideas, including democracy and revolution. The most famous was Sun Yatsen (1866–1925). Sent by his peasant family to Hawaii, he learned English and then continued his education in Hong Kong. From 1894 on, he spent his time abroad organizing revolutionary societies and seeking financial support from overseas Chinese. He joined forces with Chinese student revolutionaries studying in Japan, and together they sparked the 1911 Revolution, which brought China’s long history of monarchy to an end in 1912, to be replaced by a republic modeled on Western political ideas. China had escaped direct foreign rule but would never be the same.