A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 36

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 36

Writing, Mathematics, and Poetry

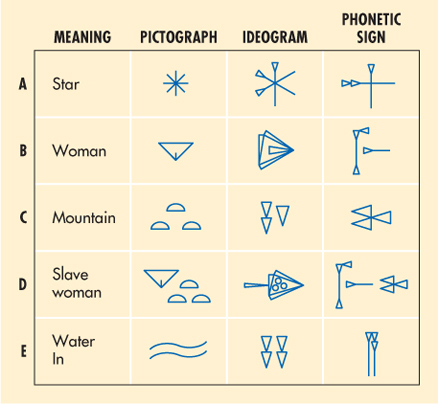

The origins of writing probably date back to the ninth millennium B.C.E., when people in southwest Asia used clay tokens as counters for record keeping. By the fourth millennium people had realized that impressing the tokens on soft clay, or drawing pictures of the tokens on clay, was simpler than making tokens. This breakthrough in turn suggested that more information could be conveyed by adding pictures of other objects, and slowly the new technology of writing developed. The result was a complex system of pictographs in which each sign pictured an object, such as “star” (line A of Figure 2.1). These pictographs were the forerunners of the Sumerian form of writing known as cuneiform (kyou-

Scribes could combine pictograms to express meaning. For example, the sign for “woman” (line B) and the sign for “mountain” (line C) were combined, literally, into “mountain woman” (line D), which meant “slave woman” because the Sumerians regularly obtained their slave women from wars against enemies in the mountains. Pictographs were initially limited in that they could not represent abstract ideas, but the development of ideograms — signs that represented ideas — made writing more versatile. Thus the sign for “star” could also be used to indicate “heaven,” “sky,” or even “god.” The real breakthrough came when scribes started using signs to represent sounds. For instance, the symbol for “water” (two parallel wavy lines) could also be used to indicate “in,” which sounded the same as the spoken word for “water” in Sumerian.

The development of the Sumerian system of writing was piecemeal, with scribes making changes and additions as they were needed. The system became so complicated that the Sumerians established scribal schools, which by 2500 B.C.E. flourished throughout the region. Students at the schools were all male, and most came from families in the middle range of urban society. Each school had a master, a teacher, and monitors. Discipline was strict, and students were caned for sloppy work and misbehavior. One graduate of a scribal school had few fond memories of the joy of learning:

My headmaster read my tablet, said:

“There is something missing,” caned me.

. . .

The fellow in charge of silence said:

“Why did you talk without permission,” caned me.

The fellow in charge of the assembly said:

“Why did you stand at ease without permission,” caned me.1

Scribal schools were primarily intended to produce individuals who could keep records of the property of temple officials, kings, and nobles. Thus writing first developed as a way to enhance the growing power of elites, not to record speech.

Sumerians wrote numbers as well as words on clay tablets, and some surviving tablets show multiplication and division problems. Mathematics was not just a theoretical matter to the people living in Mesopotamia, because the building of cities, palaces, temples, and canals demanded practical knowledge of geometry and trigonometry. The Sumerians and later Mesopotamians made significant advances in mathematics using a numerical system based on units of sixty, ten, and six, from which we derive our division of hours into sixty minutes and minutes into sixty seconds. They also developed the concept of place value — that the value of a number depends on where it stands in relation to other numbers.

Written texts were not an important part of Sumerian religious life, nor were they central to the religious practices of most of the other peoples in this region. Stories about the gods circulated orally and traveled with people when they moved up and down the rivers, so that gods often acquired new names and new characteristics over the centuries. Sumerians also told stories about heroes and kings, many of which were eventually reworked into the world’s first epic poem, the Epic of Gilgamesh (GIL-