A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 38

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 37

Chapter Chronology

Empires in Mesopotamia

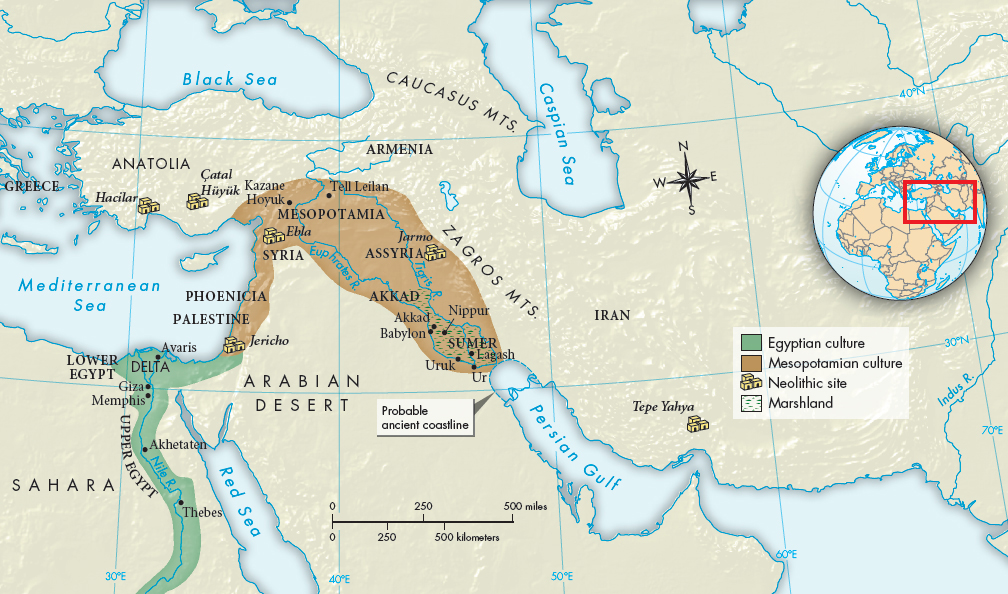

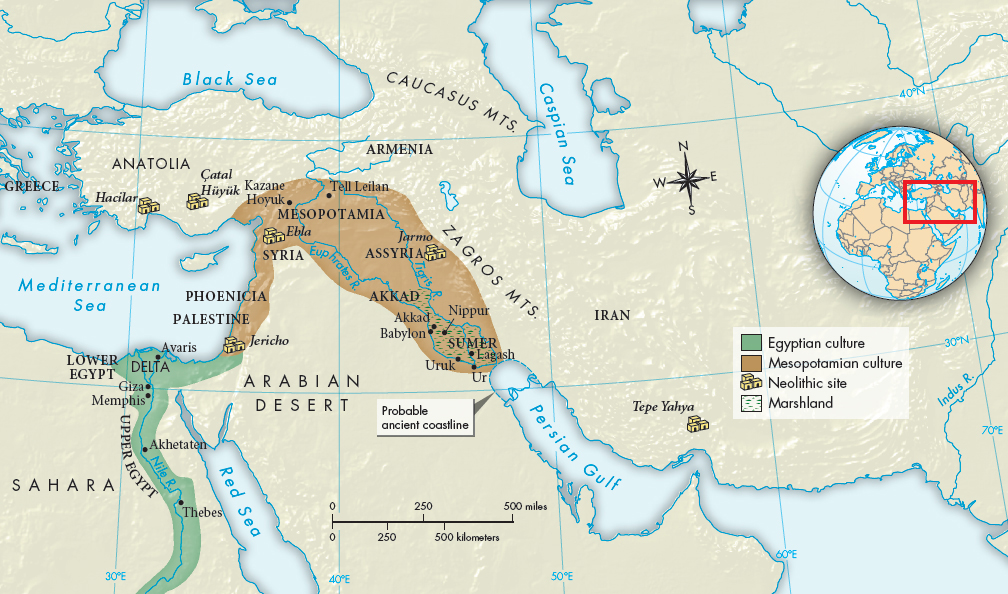

The wealth of Sumerian cities also attracted conquerors from the north. Around 2300 B.C.E. Sargon, the king of a region to the north of Sumer, conquered a number of Sumerian cities with what was probably the world’s first permanent army and created a large state. The symbol of his triumph was a new capital, the city of Akkad (AH-kahd). Sargon also expanded the Akkadian empire westward to northern Syria, which became the breadbasket of the empire. He encouraged trading networks that brought in goods from as far away as the Indus River in South Asia and what is now Turkey (Map 2.1). Sargon spoke a different language than did the Sumerians, one of the many languages that scholars identify as belonging to the Semitic language family, which includes modern-day Hebrew and Arabic. Akkadians adapted cuneiform writing to their own language, and Akkadian became the diplomatic language used over a wide area.

MAP 2.1 Spread of Cultures in Southwest Asia and the Nile Valley, ca. 3000–1640B.C.E. This map illustrates the spread of the Mesopotamian and Egyptian cultures through the semicircular stretch of land often called the Fertile Crescent. From this area, the knowledge and use of agriculture spread throughout western Asia, northern Africa, and Europe.

Sargon of Akkad This bronze head, with elaborately worked hair and beard, might portray the great conqueror Sargon of Akkad (though his name does not appear on it). The eyes were originally inlaid with precious jewels, which have since been gouged out. Produced about 2300 B.C.E., this head was found in the Assyrian capital of Nineveh, where it had been taken as loot. (© Interfoto/Alamy)

Sargon tore down the defensive walls of Sumerian cities and appointed his own sons as their rulers to help him cement his power. He also appointed his daughter, Enheduana (2285–2250 B.C.E.), as high priestess in the city of Ur. Here she wrote a number of hymns, especially those in praise of the goddess Inanna, becoming the world’s first author to put her name to a literary composition. (See “Viewpoints 2.1: Addressing the Gods in Mesopotamia and Egypt.”)

Sargon’s dynasty appears to have ruled Mesopotamia for about 150 years, and then collapsed, in part because of a period of extended drought. Various city-states then rose to power, one of which was centered on the city of Babylon. Babylon was in an excellent position to dominate trade on both the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, and it was fortunate in having a very able ruler in Hammurabi (hahm-moo-RAH-bee) (r. 1792–1750 B.C.E.). Initially a typical king of his era, he unified Mesopotamia later in his reign by using military force, strategic alliances with the rulers of smaller territories, and religious ideas. As had earlier rulers, Hammurabi linked his success with the will of the gods. He connected himself with the sun-god Shamash, the god of law and justice, and encouraged the spread of myths that explained how Marduk, the primary god of Babylon, had been elected king of the gods by the other deities in Mesopotamia. Marduk later became widely regarded as the chief god of Mesopotamia, absorbing the qualities and powers of other gods. Babylonian ideas and beliefs thus became part of the cultural mixture of Mesopotamia, which spread far beyond the Tigris and Euphrates Valleys to the shores of the Mediterranean Sea and the Harappan cities of the Indus River Valley (see “The Land and Its First Settlers, ca. 3000–1500 B.C.E.” in Chapter 3).