A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 65

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 61

The Land and Its First Settlers, ca. 3000–1500 B.C.E.

What does archaeology tell us about the Harappan civilization in India?

The subcontinent of India, a landmass as large as western Europe, juts southward into the warm waters of the Indian Ocean. Today this region is divided into the separate countries of Pakistan, Nepal, India, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka, but these divisions are recent, and for this discussion of premodern history, the entire subcontinent will be called India.

In India, as elsewhere, the possibilities for both agriculture and communication have always been shaped by geography. Some regions of the subcontinent are among the wettest on earth; others are arid deserts and scrubland. Most areas in India are warm all year, with high temperatures over 100°F; average temperatures range from 79°F in the north to 85°F in the south. Monsoon rains sweep northward from the Indian Ocean each summer. The lower reaches of the Himalaya Mountains in the northeast are covered by dense forests that are sustained by heavy rainfall. Immediately to the south are the fertile valleys of the Indus and Ganges Rivers. These lowland plains, which stretch all the way across the subcontinent, were tamed for agriculture over time, and India’s great empires were centered there. To their west are the deserts of Rajasthan and southeastern Pakistan, historically important in part because their flat terrain enabled invaders to sweep into India from the northwest. South of the great river valleys rise the jungle-

Neolithic settlement of the Indian subcontinent occurred somewhat later than in the Nile River Valley and southwestern Asia, but agriculture followed a similar pattern of development and was well established by about 7000 B.C.E. Wheat and barley were the early crops, probably having spread in their domesticated form from what is today the Middle East. Farmers also domesticated cattle, sheep, and goats and learned to make pottery.

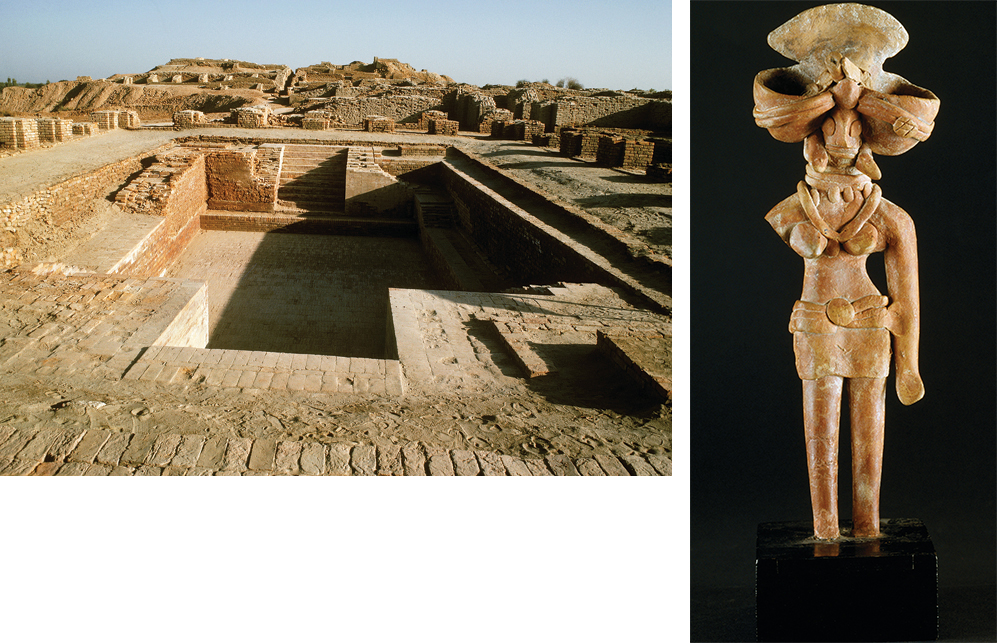

The story of the first civilization in India is one of the most dramatic in the ancient world. From the Bible, people knew about ancient Egypt and Sumer for centuries, but it was not until 1921 that archaeologists found astonishing evidence of a thriving and sophisticated Bronze Age urban culture dating to about 2500 B.C.E. at Mohenjo-

This civilization is known today as the Indus Valley or the Harappan (huh-

The Harappan civilization extended over nearly five hundred thousand square miles in the Indus Valley, making it more than twice as large as ancient Egypt or Sumer. Yet Harappan civilization was marked by striking uniformity. Throughout the region, for instance, even in small villages, bricks were made to the same standard proportion (4:2:1). Figurines of pregnant women have been found throughout the area, suggesting common religious ideas and practices.

Like Mesopotamian cities, Harappan cities were centers for crafts and trade and were surrounded by extensive farmland. Craftsmen produced ceramics decorated with geometric designs. The Harappans were the earliest known manufacturers of cotton cloth, and this cloth was so abundant that goods were wrapped in it for shipment. Trade was extensive. As early as the reign of Sargon of Akkad in the third millennium B.C.E. (see “Empires in Mesopotamia” in Chapter 2), trade between India and Mesopotamia carried goods and ideas between the two cultures, probably by way of the Persian Gulf. The Harappan port of Lothal had a stone dock 700 feet long, next to which were massive granaries and bead-

The cities of Mohenjo-

Perhaps the most surprising aspect of the elaborate planning of these cities was their complex system of drainage, which at Mohenjo-

Both Mohenjo-

The prosperity of the Indus civilization depended on constant and intensive cultivation of the rich river valley. Although rainfall seems to have been greater than in recent times, the Indus, like the Nile, flowed through a relatively dry region made fertile by annual floods and irrigation. And as in Egypt, agriculture was aided by a long, hot growing season and near-

Because no one has yet deciphered the written language of the Harappan people, their political, intellectual, and religious life is largely unknown. There clearly was a political structure with the authority to organize city planning and facilitate trade, but we do not even know whether there were hereditary kings. There are clear similarities between Harappan and Sumerian civilization, but the differences are just as clear. For instance, the Harappan script, like the Sumerian, was incised on clay tablets and seals, but it has no connection to Sumerian cuneiform, and the artistic style of the Harappan seals is distinct.

Soon after 2000 B.C.E., the Harappan civilization mysteriously declined. The port of Lothal was abandoned by about 1900 B.C.E., and other major centers came to house only a fraction of their earlier populations. Scholars have proposed many explanations for the mystery of the abandonment of these cities. The decline cannot be attributed to the arrival of powerful invaders, as was once thought. Rather it was internally generated. Environmental theories include an earthquake that led to a shift in the course of the river, or a severe drought. Perhaps the long-

Even though the Harappan people apparently lived on after scattering to villages, the large urban centers were abandoned, and key features of their high culture were lost. For the next thousand years, India had no large cities, no kiln-