A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 1013

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 1027

Chapter Chronology

Development Versus Democracy in India and Pakistan

Jawaharlal Nehru’s daughter, Indira Gandhi (no relation to Mohandas Gandhi) (1917–1984), a member of the Indian National Congress Party that led national politics in the decades after independence, became prime minister of India in 1966. She dominated Indian political life for a generation. In 1975 she subverted parliamentary democracy and proclaimed a state of emergency. The state of emergency gave her extensive powers and restricted citizens’ civil liberties. Gandhi applied her expanded powers across a broad range of areas, including combating corruption, quelling labor unrest, and jailing political opponents. She also threw the weight of the government behind a campaign of mass sterilization to reduce population growth. More than 7 million men were forcibly sterilized in 1976. Many believed that Gandhi’s emergency measures marked the end of liberal democracy, but in 1977 Gandhi called for free elections. She suffered a spectacular electoral defeat, largely because of the vastly unpopular sterilization campaign and her subversion of democracy. Her successors fell to fighting among themselves, and in 1980 she returned to power in an equally stunning electoral victory.

Separatist ethnic nationalism plagued Indira Gandhi’s last years in office. Democratic India remained a patchwork of religions, languages, and peoples, always threatening to further divide the country along ethnic or religious lines. Most notable were the 15 million Sikhs of the Punjab in northern India (see Map 31.2), with their own religion, distinctive culture, and aspirations for greater autonomy for the Punjab. By 1984 some Sikh radicals were fighting for independence. Gandhi cracked down hard and was assassinated by Sikhs in retaliation. Violence followed as Hindu mobs slaughtered over a thousand Sikhs throughout India.

One of Indira Gandhi’s sons, Rajiv Gandhi, was elected prime minister in 1984 by a landslide sympathy vote. Rajiv Gandhi departed from his mother’s and the Congress Party’s socialism and prepared the way for Finance Minister Manmohan Singh to introduce market reforms, capitalist development, and Western technology and investment from 1991 onward. These reforms were successful, and since the 1990s India’s economy has experienced explosive growth.

Though the Congress Party held power in India almost continuously after 1947, in the 1990s Hindu nationalists increasingly challenged the party’s grip on power. These nationalists argued that India was based, above all, on Hindu culture and religion and that these values had been undermined by the Western secularism of the Congress Party and the influence of India’s Muslims. The Hindu nationalist party, known as the BJP, finally gained power in 1998. The new government immediately tested nuclear devices, asserting its vision of a militant Hindu nationalism. In 2004 the United Progressive Alliance (UPA), a center-left coalition dominated by the Congress Party, regained control of the government and elected Manmohan Singh as prime minister. Under Narendra Modi, credited with the rapid economic growth of Gujarat state, the BJP returned to power after a sweeping electoral victory in 2014.

After Pakistan announced that it had developed nuclear weapons in 1998, relations between Pakistan and India worsened. In 2001 the two nuclear powers seemed poised for conflict until intense diplomatic pressure from the United States and other nations brought them back from the abyss of nuclear war. In 2005 both sides agreed to open business and trade relations and to try to negotiate a peaceful solution to the Kashmir dispute (see “Independence in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh” in Chapter 31). Tensions again increased in 2008 when a Pakistan-based terrorist organization carried out a widely televised shooting and bombing attack across Mumbai, India’s largest city, killing 164 and wounding over 300.

In the decades following the separation of Bangladesh, Pakistan alternated between civilian and military rule. General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, who ruled from 1977 to 1988, drew Pakistan into a close alliance with the United States that netted military and economic assistance. Relations with the United States chilled as Pakistan pursued its nuclear weapons program. In Afghanistan, west of Pakistan, Soviet military occupation lasted from 1979 to 1989. Civil war followed the Soviet withdrawal, and in 1996 a fundamentalist Muslim group, the Taliban, seized power. The Taliban’s leadership allowed the terrorist organization al-Qaeda to base its operations in Afghanistan. It was from Afghanistan that al-Qaeda conducted acts of terrorism like the attack on the U.S. World Trade Center and the Pentagon in 2001. Following that attack, the United States invaded Afghanistan, driving the Taliban from power and seeking to defeat al-Qaeda and its leader, Osama bin Laden.

When the United States invaded Afghanistan in 2001, Pakistani dictator General Pervez Musharraf (b. 1943) renewed the alliance with the United States, and Pakistan received billions of dollars in U.S. military aid. But U.S. combat against radical groups that imposed their vision of Islam through war or terrorist acts (including the Taliban and al-Qaeda) drove militants into regions of northwest Pakistan, where they undermined the government’s already-tenuous control. Cooperation between Pakistan and the United States in the war was often strained, but never more so than when U.S. Special Forces killed al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden on May 1, 2011. He had been hiding for years in a compound several hundred yards away from a major Pakistani military academy outside of the capital, Islamabad.

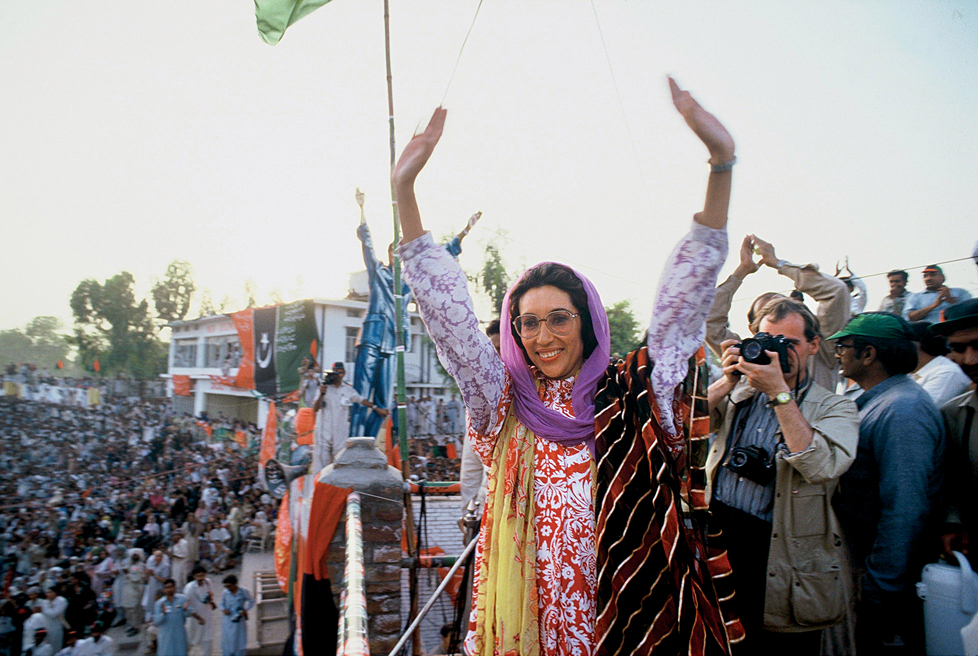

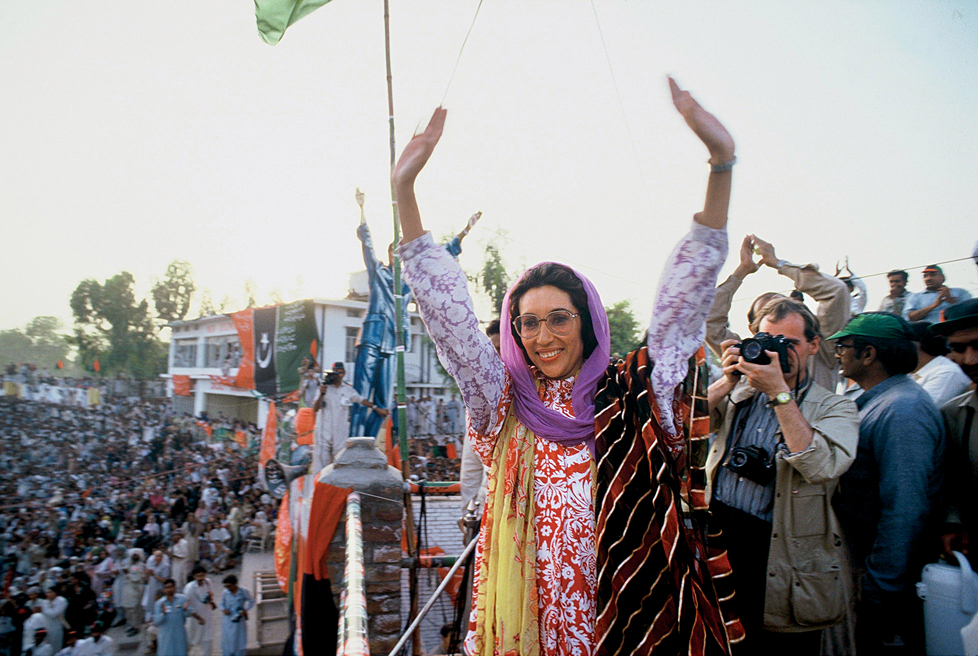

In 2007 Musharraf attempted to reshape the country’s Supreme Court by replacing the chief justice with one of his close allies, bringing about calls for his impeachment. Benazir Bhutto (1953–2007), who became the first female elected head of a Muslim state when she was elected prime minister in 1988, returned from exile to challenge Musharraf’s increasingly repressive military rule. She was assassinated while campaigning. After being defeated at the polls in 2008, Musharraf resigned and went into exile in London to avoid facing impeachment and possible corruption and murder charges. Asif Ali Zardari (b. 1955), Benazir Bhutto’s husband, won the presidency by a landslide in the elections that followed.

The Election of Benazir Bhutto Pakistan’s Benazir Bhutto became the first female prime minister of a Muslim nation in 1988. (SIPA/Spa USA)