A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 157

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 156

The Successes of Augustus

After Augustus ended the civil wars, he faced the monumental problems of reconstruction. He had to rebuild effective government, pay his army for its services, care for the welfare of the provinces, and address the danger of various groups on Rome’s frontiers. Augustus was highly successful in meeting these challenges.

Augustus claimed that he was restoring the republic, but he was actually transforming the government into one in which all power was held by a single ruler. Augustus fit his own position into the republican constitution not by creating a new office for himself but by gradually taking over many of the offices that traditionally had been held by separate people.

The Senate named him often as both consul and tribune. He was also named imperator and held control of the army, which he made a permanent standing organization. Furthermore, recognizing the importance of religion, he had himself named pontifex maximus, or chief priest. The Senate also gave him the honorary title princeps civitatis, “first citizen of the state.” That title had no official powers attached to it and had been used for centuries. Only later would princeps civitatis become the basis of the word prince, meaning “sovereign ruler,” although “prince” quite accurately describes what Augustus actually was.

Considering what had happened to Julius Caesar, Augustus wisely wielded all this power in the background, and his period of rule is officially called the “principate.” The Senate continued to exist as a court of law and deliberative body. Without specifically saying so, however, Augustus created the office of emperor. The English word emperor is derived from the Latin word imperator, an origin that reflects the fact that Augustus’s command of the army was the main source of his power. In other reforms, Augustus made provincial administration more orderly and improved its functioning. He further professionalized the army and awarded grants of land in the frontier provinces to veterans who had finished their twenty-

In the social realm, Augustus promoted marriage and childbearing through legal changes that released free women and freedwomen (female slaves who had been freed) from male guardianship if they had given birth to a certain number of children. Men and women who were unmarried or had no children were restricted in the inheritance of property. Moralists denounced any sexual relationship in which men squandered money or became subservient to those of lower social status, but no laws banned prostitution or same-

Aside from addressing legal issues and matters of state, Augustus actively encouraged poets and writers. For this reason the period of his rule is known as the “golden age” of Latin literature. Roman poets and prose writers celebrated human accomplishments in works that were highly polished, elegant in style, and intellectual in conception.

Rome’s greatest poet was Virgil (70–

Arms and the man I sing, who first made way,

predestined exile, from the Trojan shore

to Italy, the blest Lavinian strand.

Smitten of storms he was on land and sea

by violence of Heaven, to satisfy

stern Juno’s sleepless wrath; and much in war

he suffered, seeking at the last to found

the city, and bring o’er his fathers’ gods

to safe abode in Latium; whence arose

the Latin race, old Alba’s reverend lords,

and from her hills wide-

As Virgil told it, Aeneas became the lover of Dido (DIGH-

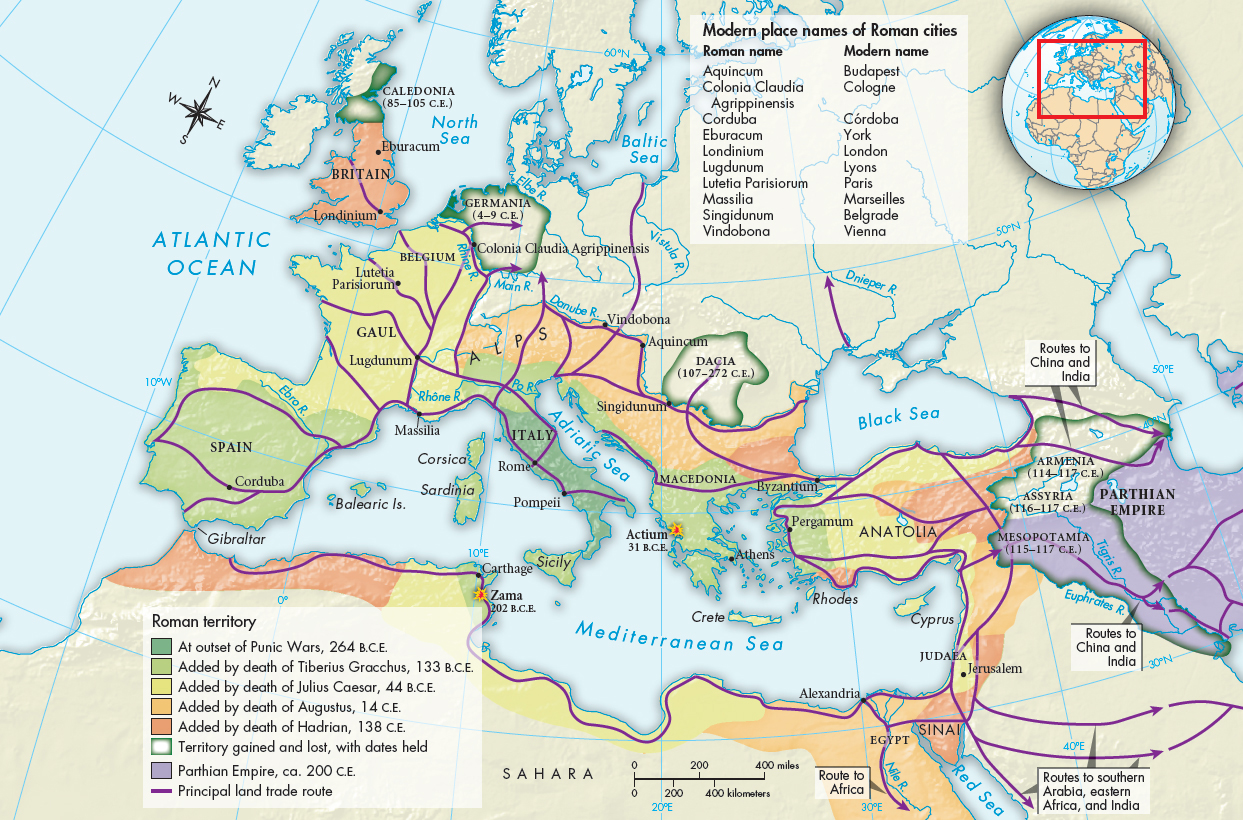

One of the most significant aspects of Augustus’s reign was Roman expansion into northern and western Europe (Map 6.2). Augustus completed the conquest of Spain, founded twelve new towns in Gaul, and saw that the Roman road system linked new settlements with one another and with Italy. After hard fighting, he made the Rhine River the Roman frontier in Germania (Germany). Meanwhile, generals conquered areas as far as the Danube River, and Roman legions penetrated the areas of modern Austria, southern Bavaria, and western Hungary. The regions of modern Serbia, Bulgaria, and Romania also fell. Within this area the legionaries built fortified camps. Roads linked these camps with one another, and settlements grew up around the camps, eventually becoming towns. Traders began to frequent the frontier and to do business with the people who lived there; as a result, for the first time, central and northern Europe came into direct and continuous contact with Mediterranean culture.

Romans did not force their culture on native people in Roman territories. However, just as earlier ambitious people in the Hellenistic world knew that the surest path to political and social advancement lay in embracing Greek culture and learning to speak Greek (see “Building a Hellenized Society” in Chapter 5), those determined to get ahead now learned Latin and adopted aspects of Roman culture.