A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 166

Global Trade

Pottery is used primarily for dishes today, but it served a surprisingly large number of purposes in the ancient world. Families used earthen pottery for cooking and tableware, for storing grains and liquids, and for lamps. On a larger scale, pottery was used for the transportation and protection of goods traded overseas, much as today’s metal storage containers are used.

The creation of pottery dates back to the Neolithic period. Few resources were required to make it, only abundant sources of good clay and wheels upon which potters could throw their vessels. Once made, the pots were baked in specially constructed kilns. Although the whole process was relatively simple, skilled potters formed groups that made utensils for entire communities. Later innovations occurred when the artisans learned to glaze their pots by applying a varnish before baking them in a kiln.

The earliest potters focused on coarse ware: plain plates, cups, and cooking pots that remained virtually unchanged throughout antiquity. Increasingly, however, potters began to decorate these pieces with simple designs. In this way pottery became both functional and decorative. One of the most popular pieces was the amphora, a large two-

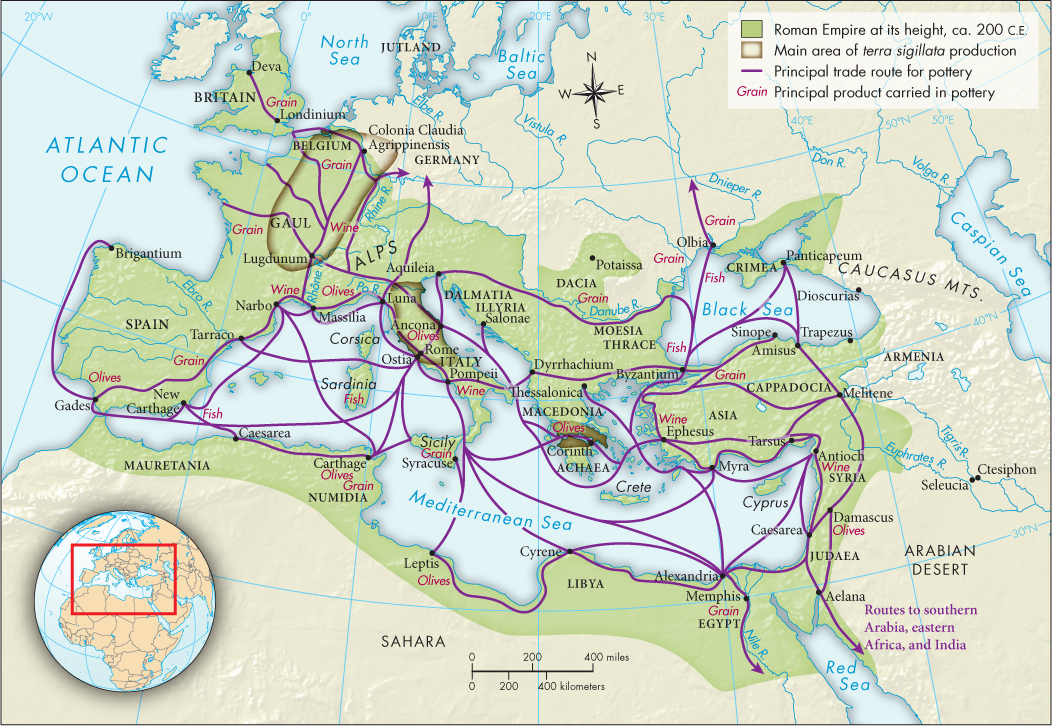

In the Hellenistic and Roman periods, amphoras became common throughout the Mediterranean and carried goods eastward to the Black Sea, Persian Gulf, and Red Sea. The Ptolemies of Egypt sent amphoras and their contents even farther, to Arabia, eastern Africa, and India. Thus merchants and mariners who had never seen the Mediterranean depended on these containers.

Other pots proved as useful as the amphora, and all became a medium of decorative art. By the eighth century B.C.E. Greek potters and artists had begun to decorate their wares by painting them with patterns and scenes from mythology, legend, and daily life. They portrayed episodes such as famous chariot races or battles from the Iliad. Some portrayed the gods, such as Dionysus at sea. These images widely spread knowledge of Greek religion and culture. In the West, especially, the Etruscans in Italy and the Carthaginians in North Africa eagerly welcomed the pots, their decoration, and their ideas. The Hellenistic kings shipped these pots as far east as China. Pottery thus served as a means of cultural exchange among people scattered across huge portions of the globe.

The Romans took the manufacture of pottery to an advanced stage by introducing a wider range of vessels and by making some in industrial-