A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 220

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 217

Migrating Peoples

How did the barbarians shape social, economic, and political structures in Europe and western Asia?

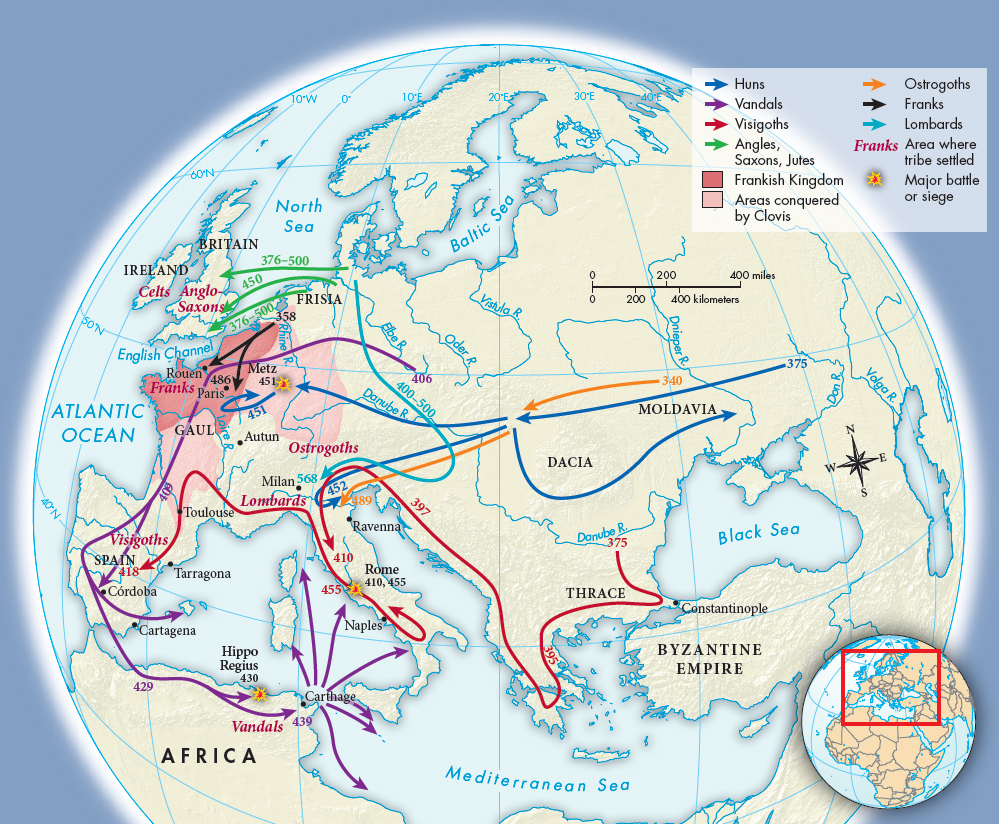

Along with The Confessions, Augustine’s other major work was The City of God, a work that develops a Christian view of history and was written in direct response to what many people in Rome thought was a disaster: the capture of the city in 410 by Visigothic forces. The Visigoths were one of the many peoples moving west and south from Central Asia and northern Europe that the Romans — and later historians — labeled “barbarians” (Map 8.2). The word barbarian comes from the Greek barbaros, meaning someone who did not speak Greek. (To the Greeks, others seemed to be speaking nonsense syllables; barbar is the Greek equivalent of “blah-

Barbarians included many different ethnic groups with social and political structures, languages, laws, and beliefs developed in central and northern Europe and western Asia over many centuries. Among the largest barbarian groups were the Celts (whom the Romans called Gauls) and Germans; Germans were further subdivided into various tribes, such as Ostrogoths, Visigoths, Burgundians, and Franks. Celt and German are often used as ethnic terms, but they are better understood as linguistic terms, a Celt being a person who spoke a Celtic language, an ancestor of the modern Gaelic or Breton languages, and a German one who spoke a Germanic language, an ancestor of modern German, Dutch, Danish, Swedish, and Norwegian. Celts, Germans, and other barbarians brought their customs and traditions with them when they moved south and west, and these gradually combined with classical and Christian customs and beliefs to form new types of societies. From this cultural mix the Franks emerged as an especially strong and influential force, and they built a lasting empire (see “Frankish Rulers and Their Territories”).