A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 209

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 203

Chapter Chronology

The Sassanid Empire and Conflicts with Byzantium

For several centuries the Sassanid empire of Persia was Byzantium’s most regular foe. Ardashir I (r. 224–243), the ruler of a small state and the first of the Sassanid dynasty, conquered the Parthian empire in 226 (see Map 6.2). Ardashir kept expanding his holdings to the east and northwest. He moved the capital of this new Sassanid empire to Ctesiphon (TEH-suh-fahn), in the fertile Tigris-Euphrates Valley, from where it retained control of much of the Persian Gulf. Like all empires, the Sassanid depended on agriculture for its economic prosperity, but its location also proved well suited for commerce (see Map 8.1). A lucrative caravan trade linked the Sassanid empire to the Silk Road and China (see “Global Trade: Silk.”). Persian metalwork, textiles, and glass were exchanged for Chinese silks, and this trade brought about considerable cultural contact between the Sassanids and the Chinese.

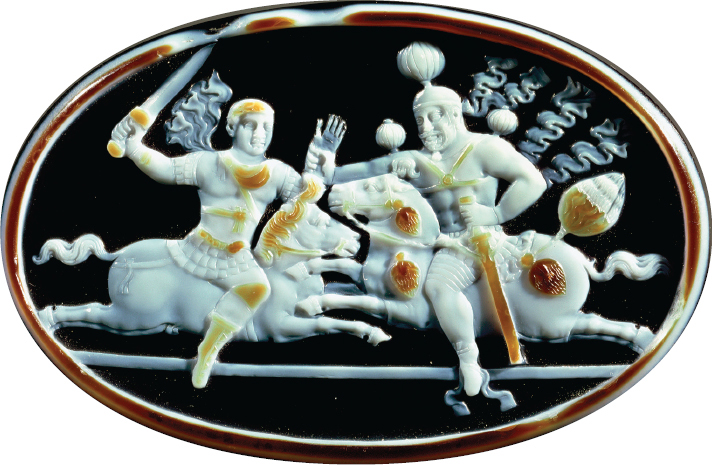

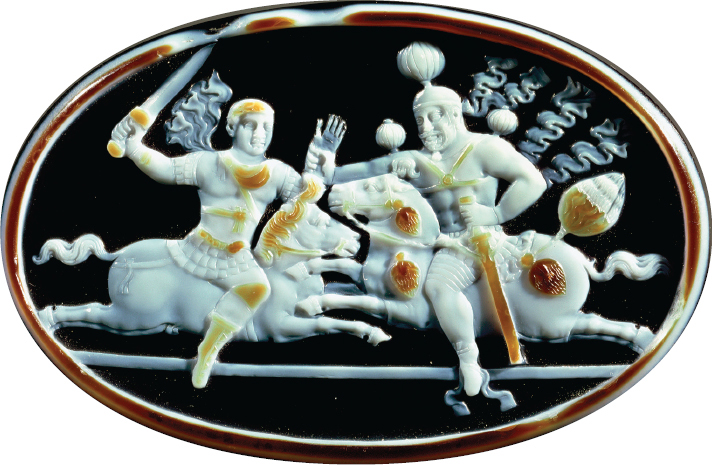

Sassanid Cameo In this cameo — a type of jewelry made by carving into a multi colored piece of rock — the Sassanid king Shapur and the Byzantine emperor Valerian fight on horseback, each identifiable by his distinctive clothing and headgear. This does not record an actual hand-to-hand battle, but uses the well-muscled rulers as symbols of their empires. (Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY)

Whereas the Parthians had tolerated many religions, the Sassanid Persians made Zoroastrianism the official state religion. Religion and the state were inextricably tied together. The king’s power rested on the support of nobles and Zoroastrian priests who monopolized positions in the court and in the imperial bureaucracy. A highly elaborate court ceremonial and ritual exalted the status of the king and emphasized his semidivine pre-eminence over his subjects. (The Byzantine monarchy, the Roman papacy, and the Muslim caliphate subsequently copied aspects of this Persian ceremonial.)

Adherents to religions other than Zoroastrianism, such as Jews and Christians, faced discrimination. The Jewish population in the Sassanid empire was sizable because the Romans had forced many Jews out of Israel and Judaea after a series of revolts against Roman rule, a dispersal later termed the diaspora. Jews suffered intermittent persecution under the Sassanids, as did Christians, whom followers of Zoroastrianism saw as being connected to Rome and Constantinople.

An expansionist foreign policy brought Persia into frequent conflict with Rome and then with Byzantium. Neither side was able to achieve a clear-cut victory until the early seventh century, when the Sassanids advanced all the way to the Mediterranean and even took Egypt in 621. Their victory would be very short-lived, however, as the taxes required to finance the wars and conflicts over the succession to the throne had weakened the Persians. Under Emperor Heraclius I (r. 610–641), the Byzantines crushed the Persians in a series of battles ending with one at Nineveh in 627. Just five years later, the first Arabic forces inspired by Islam entered Persian territories, and by 651 the Sassanid dynasty had collapsed (see “Islamic States and Their Expansion” in Chapter 9).