A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 251

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 247

Women in Classical Islamic Society

Before Islam, Arab tribal law gave women virtually no legal powers. Girls were sold into marriage by their guardians, and their husbands could terminate the union at will. Also, women had virtually no property or succession rights. Seen from this perspective, the Qur’an sought to improve the social position of women.

The hadith — records of what Muhammad said and did, and what believers in the first two centuries after his death believed he said and did (see “Muhammad’s Rise as a Religious Leader”) — provide information about the Prophet’s wives. Some hadith portray them as subject to common human frailties, such as jealousy; others report miraculous events in their lives. Most hadith describe the wives as “mothers of the believers” — models of piety and righteousness whose every act illustrates their commitment to promoting God’s order on earth by personal example.

The Qur’an, like the religious writings of other traditions, represents moral precept rather than social practice, and the texts are open to different interpretations. Modern scholars tend to agree that the Islamic sacred book intended women to be the spiritual equals of men and gave them considerable economic rights. In the early Umayyad period, moreover, women played active roles in the religious, economic, and political life of the community. They owned property, had freedom of movement and traveled widely, and participated with men in public religious rituals and observances. But this Islamic ideal of women and men having equal value to the community did not last, and, as Islamic society changed, the precepts of the Qur’an were interpreted in more patriarchal ways. (See “Listening to the Past: Abu Hamid al-Ghazali on the Etiquette of Marriage.”)

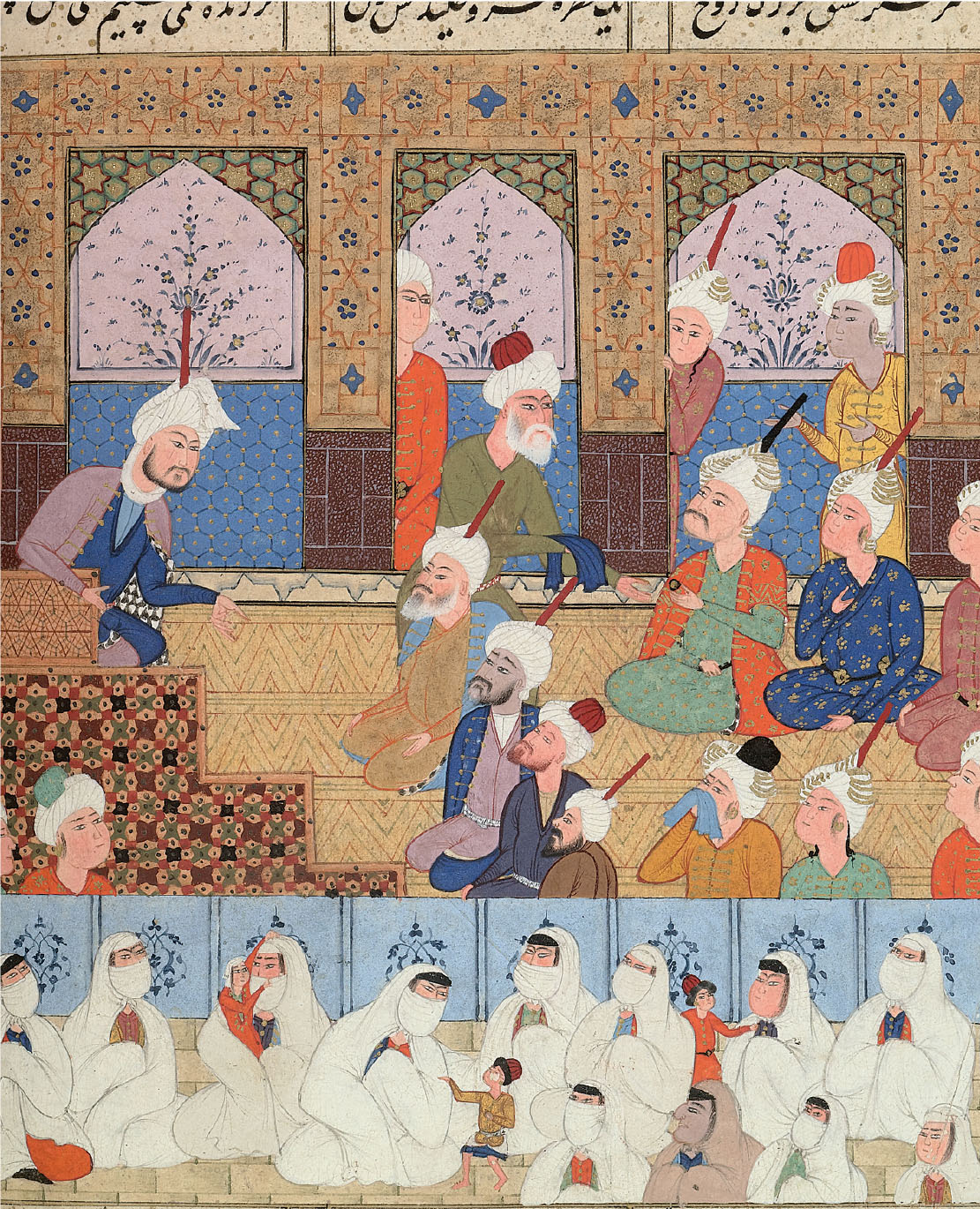

Although the hadith usually depict women in terms of moral virtue, domesticity, and saintly ideals, they also show some prominent women in political roles. For example, Aisha, daughter of the first caliph and probably Muhammad’s favorite wife, played a leading role in rallying support for the movement opposing Ali, who succeeded Uthman in 656 (see “The Caliphate and the Split Between Shi’a and Sunni Alliances”). However, by the Abbasid period the status of women had declined. The practices of the Byzantine and Persian lands that had been conquered, including seclusion of women, were absorbed. The supply of slave women increased substantially. Some scholars speculate that as wealth replaced ancestry as the main criterion of social status, men more and more viewed women as possessions, as a form of wealth.

Men were also seen as dominant in their marriages. The Qur’an states that “men are in charge of women because Allah hath made the one to excel the other, and because they (men) spend of their property (for the support of women). So good women are obedient, guarding in secret that which Allah hath guarded.”2 A thirteenth-

In many present-