A History of World Societies:

Printed Page 253

A History of World Societies Value

Edition: Printed Page 251

Trade and Commerce

Why did trade thrive in Muslim lands?

Unlike the Christian West or the Confucian East, Islam looked favorably on profit-

The Qur’an, moreover, has no prohibition against trade with Christians or other unbelievers. In fact, non-

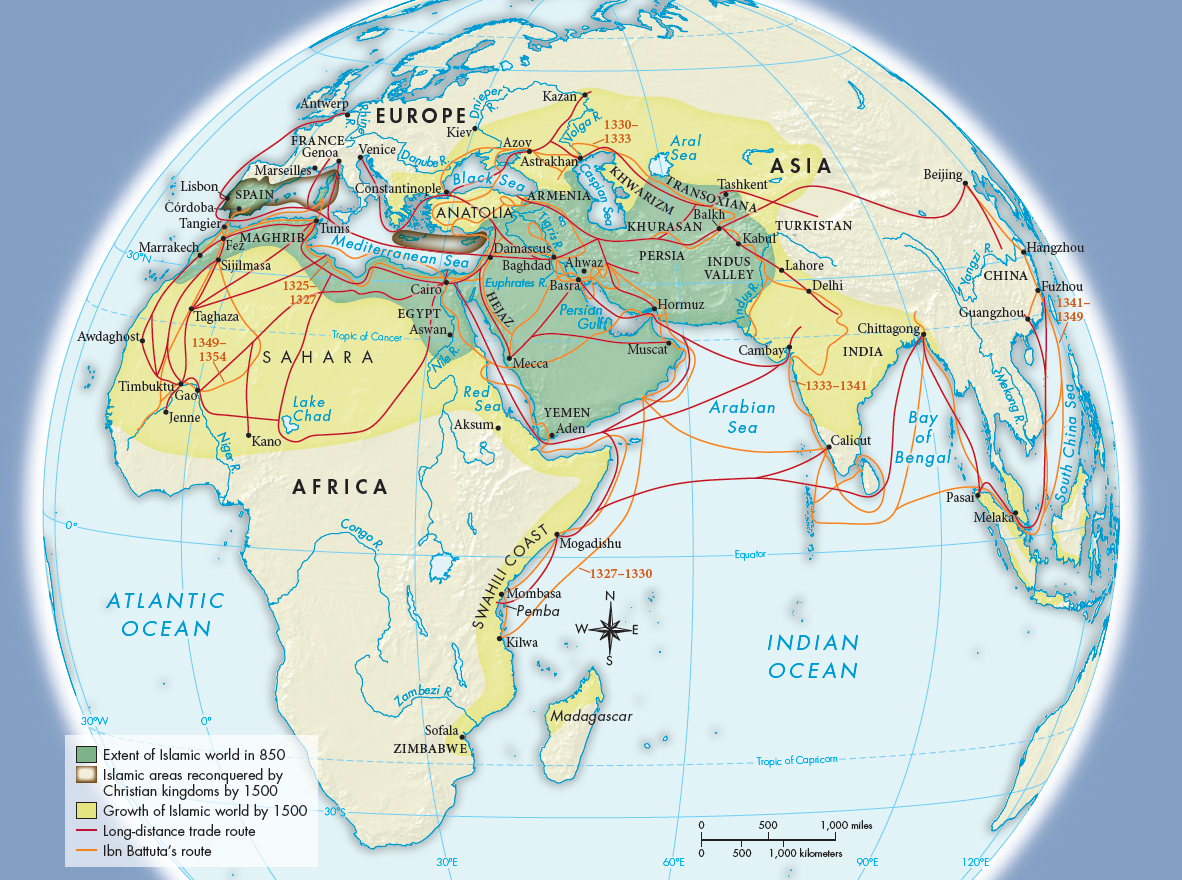

Waterways served as the main commercial routes of the Islamic world (Map 9.2). They included the Mediterranean and Black Seas; the Caspian Sea and the Volga River, which gave access deep into Russia; the Aral Sea, from which caravans departed for China; the Gulf of Aden; and the Arabian Sea and the Indian Ocean, which linked the Persian Gulf region with eastern Africa, the Indian subcontinent, and eventually Indonesia and the Philippines.

Cairo was a major Mediterranean entrepôt for intercontinental trade. Foreign merchants from Central Asia, Persia, Iraq, Europe (especially Venice), the Byzantine Empire, and Spain sailed up the Nile to the Aswan region, traveled east from Aswan by caravan to the Red Sea, and then sailed down the Red Sea to Aden, where they entered the Indian Ocean on their way to India. They exchanged textiles, glass, gold, silver, and copper for Asian spices, dyes, and drugs and for Chinese silks and porcelains. Muslim and Jewish merchants dominated the trade with India, and all spoke and wrote Arabic. Their commercial practices included the sakk (the Arabic word is the root of the English check), an order to a banker to pay money held on account to a third party; the practice can be traced to Roman Palestine. Muslims also developed other business innovations, such as the bill of exchange, a written order from one person to another to pay a specified sum of money to a designated person or party, and the idea of the joint stock company, an arrangement that lets a group of people invest in a venture and share its profits (and losses) in proportion to the amount each has invested.

Trade also benefited from improvements in technology. The adoption from the Chinese of the magnetic compass, an instrument for determining directions at sea by means of a magnetic needle turning on a pivot, greatly helped navigation of the Arabian Sea and the Indian Ocean. The construction of larger ships led to a shift in long-

In this period Egypt became the center of Muslim trade, benefiting from the decline of Iraq caused by the Mongol capture of Baghdad and the fall of the Abbasid caliphate (see “The Mongol Invasions”). Beginning in the late twelfth century Persian and Arab seamen sailed down the east coast of Africa and established trading towns between Somalia and Sofala (see “The East African City-States” in Chapter 10). These thirty to fifty urban centers — each merchant-

A private ninth-

Imported from India: tigers, leopards, elephants, leopard skins, red rubies, white sandal-

From China: aromatics, silk, porcelain, paper, ink, peacocks, fiery horses, saddles, felts, cinnamon

From the Byzantines: silver and gold vessels, embroidered cloths, fiery horses, slave girls, rare articles in red copper, strong locks, lyres, water engineers, specialists in plowing and cultivation, marble workers, and eunuchs

From Egypt: ambling donkeys, fine cloths, papyrus, balsam oil, and, from its mines, high-

From the Khazars [a people living on the northern shore of the Black Sea]: slaves, slave women, armor, helmets, and hoods of mail

From Ahwaz [a city in southwestern Persia]: sugar, silk brocades, castanet players and dancing girls, kinds of dates, grape molasses, and candy.5

Did Muslim economic activity amount to a kind of capitalism? If capitalism is defined as private (not state) ownership of the means of production, the production of goods for sale, profit as the main motive for economic activity, competition, and a money economy, then, unquestionably, the medieval Muslim economy had capitalistic features. Until the sixteenth century much more world trade went through Muslim than European hands.

One byproduct of the extensive trade through Muslim lands was the spread of useful plants. Cotton, sugarcane, and rice spread from India to other places with suitable climates. Citrus fruits made their way to Muslim Spain from Southeast Asia and India. The value of this trade contributed to the prosperity of the Abbasid era.