Expression in the Media: Print, Broadcast, and Online

THE HOUSE UN-

During the Cold War, a vigorous campaign led by Joseph McCarthy, an ultraconservative senator from Wisconsin, tried to rid both government and the media of so-

Although the First Amendment protects an individual’s right to hold controversial political views, network executives either sympathized with the anticommunist movement or feared losing ad revenue. At any rate, the networks did not stand up to the communist witch-

The communist witch-

| ELSEWHERE IN MEDIA & CULTURE | ||

|

|

||

|

THE ADVENTURES OF HUCKLEBERRY FINN IS STILL THE MOST- |

||

| HOW IS ADVERTISING SPENDING CHANGING? | ||

| 39% Share of U.S. advertising dollars that go to television | 25% Share of U.S. advertising dollars that go to digital/mobile | 10% Share of U.S. advertising dollars that go to newspapers |

| p. 385 | ||

| HOW PIRACY CHANGED THE MUSIC INDUSTRY p. 140 | ||

The FCC Regulates Broadcasting

Drawing on the argument that limited broadcast signals constitute a scarce national resource, the Communications Act of 1934 mandated that radio broadcasters operate in “the public interest, convenience, and necessity.” Since the 1980s, however, with cable and, later, DBS increasing channel capacity, station managers have lobbied to own their airwave assignments. Although the 1996 Telecommunications Act did not grant such ownership, stations continue to challenge the “public interest” statute. They argue that because the government is not allowed to dictate content in newspapers, it should not be allowed to control broadcasting via licenses or mandate any broadcast programming.

Two cases—

In contrast, five years later, in Miami Herald Publishing Co. v. Tornillo, the Supreme Court sided with the newspaper. A political candidate, Pat Tornillo Jr., requested space to reply to an editorial opposing his candidacy. Previously, Florida had a right-

Dirty Words, Indecent Speech, and Hefty Fines

In theory, communication law prevents the government from censoring broadcast content. Accordingly, the government may not interfere with programs or engage in prior restraint, although it may punish broadcasters for indecency or profanity after the fact. Over the years, a handful of radio stations have had their licenses suspended or denied after an unfavorable FCC review of past programming records. Concerns over indecent broadcast programming began in 1937 when NBC was scolded by the FCC for running a sketch featuring comic actress Mae West on ventriloquist Edgar Bergen’s network program. West had the following conversation with Bergen’s famous wooden dummy, Charlie McCarthy:

WEST: That’s all right. I like a man that takes his time. Why don’t you come home with me? I’ll let you play in my woodpile . . . you’re all wood and a yard long. . . .

CHARLIE: Oh, Mae, don’t, don’t . . . don’t be so rough. To me love is peace and quiet.

WEST: That ain’t love—

After the sketch, West did not perform on radio for years. Ever since, the FCC has periodically fined or reprimanded stations for indecent programming, especially during times when children might be listening.

INDECENT SPEECH

The sexual innuendo of an “Adam and Eve” radio sketch between sultry film star Mae West and dummy Charlie McCarthy (voiced by ventriloquist Edgar Bergen) on a Sunday evening in December 1937 enraged many listeners of Bergen’s program. The networks banned West from further radio appearances for what was considered indecent speech. © Bettmann/Corbis

In the 1960s, topless radio featured deejays and callers discussing intimate sexual subjects in the middle of the afternoon. The government curbed the practice in 1973, when the chairman of the FCC denounced topless radio as “a new breed of air pollution . . . with the suggestive, coaxing, pear-

2 BROKE GIRLS has become a favorite target of the Parents Television Council (PTC) since its debut in 2011. The PTC, which collects indecency complaints via its Web site and directs them to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), evaluates shows based on occurrences of gratuitous sex, explicit dialogue, violent content, or obscene language. 2 Broke Girls attracts the PTC’s ire for its frequent references to sex. CBS/Photofest

The current precedent for regulating broadcast indecency stems from a complaint to the FCC in 1973. In the middle of the afternoon, WBAI, a nonprofit Pacifica network station in New York, aired George Carlin’s famous comedy sketch about the seven dirty words that could not be uttered by broadcasters. A father, riding in a car with his fifteen-

This ruling provides the rationale for the indecency fines that the FCC has frequently leveled against programs and stations that have carried indecent programming during daytime and evening hours. While Howard Stern and his various bosses held the early record for racking up millions in FCC indecency fines in the 1990s—

After the FCC later fined broadcasters for several instances of “fleeting expletives” during live TV shows, the four major networks sued the FCC on grounds that their First Amendment rights had been violated. In its fining flurry, the FCC was partly responding to organized campaigns aimed at Howard Stern’s vulgarity and at the Janet Jackson exposed-

Political Broadcasts and Equal Opportunity

In addition to indecency rules, another law that the print media do not encounter is Section 315 of the 1934 Communications Act, which mandates that during elections, broadcast stations must provide equal opportunities and response time for qualified political candidates. In other words, if broadcasters give or sell time to one candidate, they must give or sell the same opportunity to others. Local broadcasters and networks have fought this law for years, complaining that it has required them to give marginal third-

Due to Section 315, many stations from the late 1960s through the 1980s refused to air movies starring Ronald Reagan. Because his film appearances did not count as bona fide news stories, politicians opposing Reagan as a presidential candidate could demand free time in markets that ran old Reagan movies. For the same reason, in 2003, TV stations in California banned the broadcast of Arnold Schwarzenegger movies when he became a candidate for governor, and dozens of stations nationwide preempted an episode of Saturday Night Live that was hosted by Al Sharpton, a Democratic presidential candidate.

However, supporters of the equal opportunity law argue that it has provided forums for lesser-

The Demise of the Fairness Doctrine

Considered an important corollary to Section 315, the Fairness Doctrine was to controversial issues what Section 315 is to political speech. Initiated in 1949, this FCC rule required stations (1) to air and engage in controversial-

Over the years, broadcasters argued that mandating opposing views every time a program covered a controversial issue was a burden not required of the print media, and that it forced many of them to refrain from airing controversial issues. As a result, the Fairness Doctrine ended with little public debate in 1987 after a federal court ruled that it was merely a regulation rather than an extension of Section 315 law.

Since 1987, however, periodic support for reviving the Fairness Doctrine has surfaced. Its supporters argue that broadcasting is fundamentally different from—

Communication Policy and the Internet

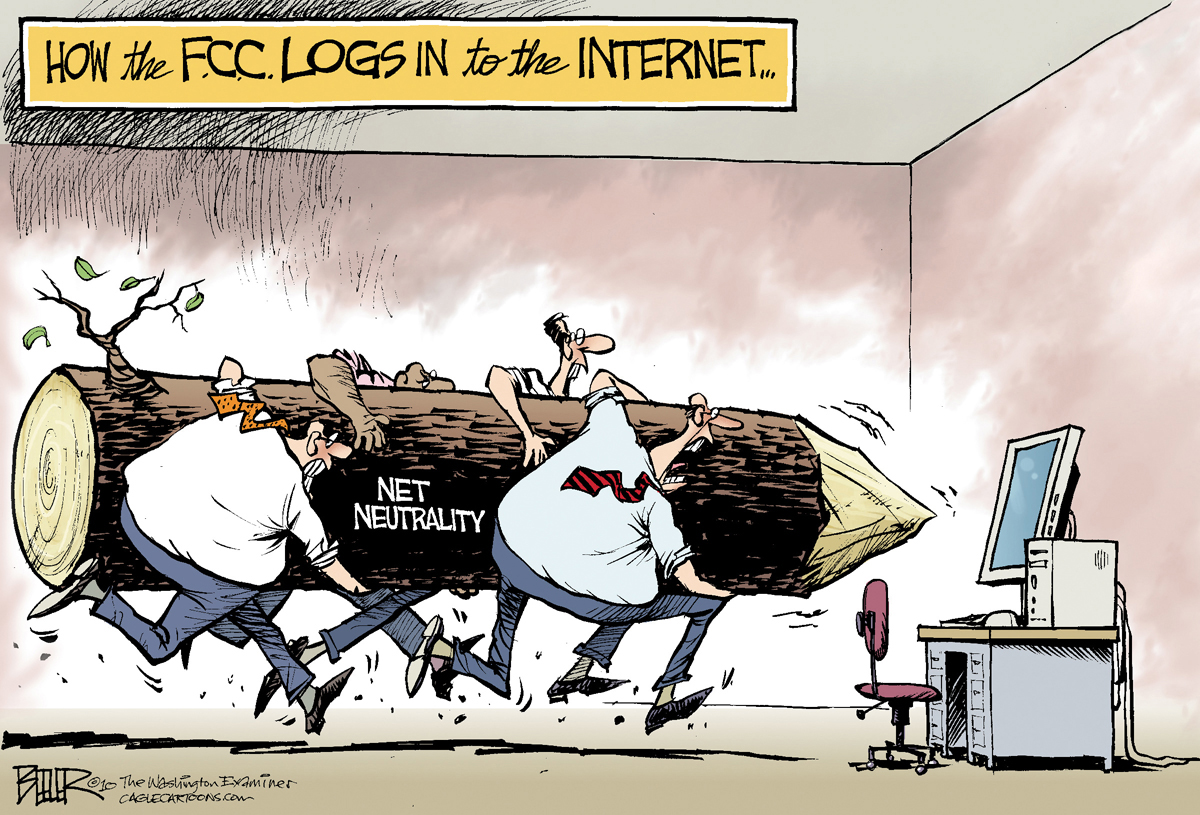

Nate Beeler/Cagle Cartoons

Many have looked to the Internet as the one true venue for unlimited free speech under the First Amendment because it is not regulated by the government, it is not subject to the Communications Act of 1934, and little has been done in regard to self-

Public conversations about the Internet have not typically revolved around ownership. Instead, the debates have focused on First Amendment issues, such as civility and pornography. Not unlike the public’s concern over television’s sexual and violent images, the scrutiny of the Internet is mainly about harmful images and information online, not about who controls it and for what purposes. However, as we watch the rapid expansion of the Internet, an important question confronts us: Will the Internet continue to develop as a democratic medium? By 2014, the answer to that question was still unclear. In late 2010, the FCC created net neutrality rules for wired (cable and DSL) broadband providers, requiring that they provide the same access to all Internet services and content. But the FCC’s net neutrality rules have been rejected by federal courts twice, most recently in 2014. The courts argued that because the FCC had not defined the Internet as a utility, it couldn’t regulate it in this manner. Telecommunication companies were pleased with the decision, as they don’t want any rules governing how they distribute access to the Internet. However, citizens and entrepreneurs have opposed an unregulated system that would allow telecommunication companies to create fast lanes (for those who pay more) and slow lanes on the Internet. The debate generated a record number of comments to the FCC—

The eventual outcome will determine whether broadband Internet connections will be defined as an essential utility to which everyone has access and for which rates are controlled (like electricity or phone service) or as an information service for which Internet service providers can charge as much as they wish (as with cable TV).

Critics and observers hope that a vigorous debate about ownership will develop—

EXAMINING ETHICS

A Generation Of Copyright Criminals?

As a student reading this book, you have probably already composed plenty of research papers and quoted, with attribution, from various printed sources. This is a routine practice, and you are within the legal bounds of fair use of the sources you sampled. The concept of fair use has existed in U.S. case law for more than 150 years.

But what if you are composing a song or creating a video, and you decide to sample bits of music or a clip of film? Under current law, you have little protection and may be subject to a lawsuit from the recording or motion-

As inexpensive digital technology became available, artists began sampling sounds and images, much like scholars and writers might sample texts. University of Iowa communication studies professor Kembrew McLeod explains that in the late 1980s, sampling “was a creative window that had been forced open by hip-

DJ GIRL TALK mixes his beats with samples from other artists to create new music. Joey Foley/FilmMagic/Getty Images

Nevertheless, some artists are still trying. Pittsburgh-

Despite the threat of lawsuits, Gillis and an independent label—

The uneven and unclear rules for the use of sound, images, video, and text have become one of the most contentious issues of today’s digital culture. As digital media make it easier than ever to create and re-

“There’s no way to kill this technology. You can only criminalize its use,” Harvard Law professor and Internet activist Lawrence Lessig notes. “If this is a crime, we have a whole generation of criminals.”4