U.S. Popular Music and the Formation of Rock

Popular music, or pop music, is music that appeals either to a wide cross section of the public or to sizable subdivisions within the larger public based on age, region, or ethnic background (e.g., teenagers, southerners, and Mexican Americans). U.S. pop music today encompasses styles as diverse as blues, country, Tejano, salsa, jazz, rock, reggae, punk, hip-

The Rise of Pop Music

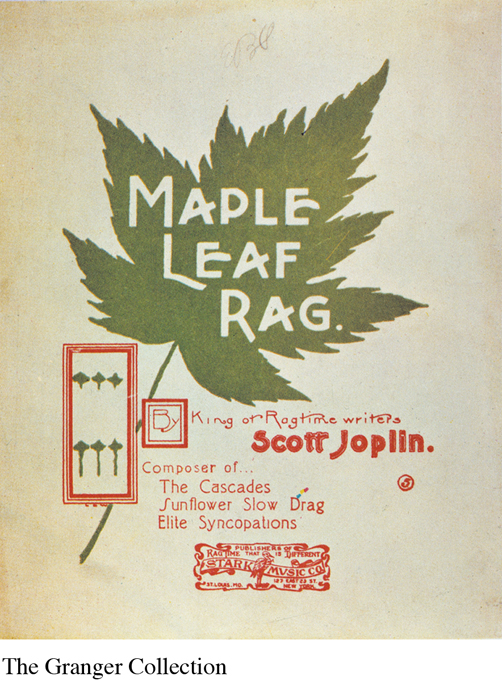

SCOTT JOPLIN (1868–1917) published more than fifty compositions during his life, including “Maple Leaf Rag”—arguably his most famous piece.

Although it is commonly assumed that pop music developed simultaneously with the phonograph and radio, it actually existed prior to these media. In the late nineteenth century, the sale of sheet music for piano and other instruments sprang from a section of Broadway in Manhattan known as Tin Pan Alley, a derisive term used to describe the sound of these quickly produced tunes, which supposedly resembled cheap pans clanging together. Tin Pan Alley’s tradition of song publishing began in the late 1880s with such music as the marches of John Philip Sousa and the ragtime piano pieces of Scott Joplin. It continued through the first half of the twentieth century with the show tunes and vocal ballads of Irving Berlin, George Gershwin, and Cole Porter, and into the 1950s and 1960s with such rock-

At the turn of the twentieth century, with the newfound ability of song publishers to mass-

As sheet music grew in popularity, jazz developed in New Orleans. An improvisational and mostly instrumental musical form, jazz absorbed and integrated a diverse body of musical styles, including African rhythms, blues, and gospel. Jazz influenced many bandleaders throughout the 1930s and 1940s. Groups led by Louis Armstrong, Count Basie, Tommy Dorsey, Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman, and Glenn Miller were among the most popular of the “swing” jazz bands, whose rhythmic music also dominated radio, recordings, and dance halls in their day.

The first pop vocalists of the twentieth century were products of the vaudeville circuit, which radio, movies, and the Depression would bring to an end in the 1930s. In the 1920s, Eddie Cantor, Belle Baker, Sophie Tucker, and Al Jolson were all extremely popular. By the 1930s, Rudy Vallée and Bing Crosby had established themselves as the first “crooners,” or singers of pop standards. Bing Crosby also popularized Irving Berlin’s “White Christmas,” one of the most covered songs in recording history. (A song recorded or performed by another artist is known as cover music.) Meanwhile, the Andrews Sisters’ boogie-

Frank Sinatra arrived in the 1940s, and his romantic ballads foreshadowed the teen love songs of rock and roll’s early years. Nicknamed “the Voice” early in his career, Sinatra, like Crosby, parlayed his music and radio exposure into movie stardom. Helped by radio, pop vocalists like Sinatra were among the first vocalists to become popular with a large national teen audience. Their record sales helped stabilize the industry, and in the early 1940s, Sinatra’s concerts caused the kind of audience riots that would later characterize rock-

Rock and Roll Is Here to Stay

ROBERT JOHNSON (1911–1938), who ranks among the most influential and innovative American guitarists, played the Mississippi delta blues and was a major influence on early rock and rollers, especially the Rolling Stones and Eric Clapton. His intense slide-

The cultural storm called rock and roll hit in the mid-

The migration of southern blacks to northern cities in search of better jobs during the first half of the twentieth century helped spread different popular music styles. In particular, blues music, the foundation of rock and roll, came to the North. Influenced by African American spirituals, ballads, and work songs from the rural South, blues music was exemplified in the work of Robert Johnson, Ma Rainey, Son House, Bessie Smith, Charley Patton, and others. The introduction in the 1930s of the electric guitar—

BESSIE SMITH (1895–1937) is considered the best female blues singer of the 1920s and 1930s. Mentored by the famous Ma Rainey, Smith had many hits, including “Down Hearted Blues” and “Gulf Coast Blues.” She also appeared in the 1929 film St. Louis Blues.

During this time, blues-

Another reason for the growth of rock and roll can be found in the repressive and uneasy atmosphere of the 1950s. To cope with the threat of the atomic bomb, the Cold War, and communist witch-

Perhaps the most significant factor in the growth of rock and roll was the beginning of the integration of white and black cultures. In addition to increased exposure of black literature, art, and music, several key historical events in the 1950s broke down the borders between black and white cultures. In 1948, President Truman signed an executive order integrating the armed forces, bringing young men from very different ethnic and economic backgrounds together at the time of the Korean War. Even more significant was the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954. With this ruling, “separate but equal” laws, which had kept white and black schools, hotels, restaurants, rest rooms, and drinking fountains segregated for decades, were declared unconstitutional. A cultural reflection of the times, rock and roll would burst forth from the midst of these social and political tensions.

Rock Muddies the Waters

In the 1950s, legal integration accompanied a cultural shift, and the music industry’s race and pop charts blurred. White deejay Alan Freed had been playing black music for his young audiences in Cleveland and New York since the early 1950s, and such white performers as Johnnie Ray and Bill Haley had crossed over to the race charts to score R&B hits. Meanwhile, black artists like Chuck Berry were performing country songs, and for a time Ray Charles even played in an otherwise all-

High and Low Culture

ROCK-

In 1956, Chuck Berry’s “Roll Over Beethoven” merged rock and roll, considered low culture by many, with high culture, thus forever blurring the traditional boundary between these cultural forms with lyrics like “You know my temperature’s risin’ / the jukebox is blowin’ a fuse . . . / Roll over Beethoven / and tell Tchaikovsky the news.” Although such early rock-

The blurring of cultures works both ways. Since the advent of rock and roll, some musicians performing in traditionally high-

Masculinity and Femininity

Rock and roll was also the first popular music genre to overtly confuse issues of sexual identity and orientation. Although early rock and roll largely attracted males as performers, the most fascinating feature of Elvis Presley, according to the Rolling Stones’ Mick Jagger, was his androgynous appearance.18 During this early period, though, the most sexually outrageous rock-

Wearing a pompadour hairdo and assaulting his Steinway piano, Little Richard was considered rock and roll’s first drag queen, blurring the boundary between masculinity and femininity. Little Richard has said that given the reality of American racism, he blurred gender and sexuality lines because he feared the consequences of becoming a sex symbol for white girls: “I decided that my image should be crazy and way out so that adults would think I was harmless. I’d appear in one show dressed as the Queen of England and in the next as the pope.”19 Little Richard’s playful blurring of gender identity and sexual orientation paved the way for performers like David Bowie, Elton John, Boy George, Annie Lennox, Prince, Grace Jones, Marilyn Manson, Lady Gaga, and Adam Lambert.

The Country and the City

Rock and roll also blurred geographic borders between country and city, between the white country & western music of Nashville and the black urban rhythms of Memphis. Early white rockers such as Buddy Holly and Carl Perkins combined country or hillbilly music, southern gospel, and Mississippi delta blues to create a sound called rockabilly. At the same time, an urban R&B influence on early rock came from Fats Domino (“Blueberry Hill”), Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton (“Hound Dog”), and Big Joe Turner (“Shake, Rattle, and Roll”). Many of these songs, first popular on R&B labels, crossed over to the pop charts during the mid to late 1950s (although many were performed by more widely known white artists). Chuck Berry borrowed from white country & western music (an old country song called “Ida Red”) and combined it with R&B to write “Maybellene.” His first hit, the song was No. 1 on the R&B chart in July 1955 and crossed over to the pop charts the next month.

Although rock lyrics in the 1950s may not have been especially provocative or overtly political, soaring record sales and the crossover appeal of the music itself represented an enormous threat to long-

The North and the South

KATY PERRY Many of today’s biggest pop music stars show off not just catchy radio-

Not only did rock and roll muddy the urban and rural terrain, but it also combined northern and southern influences. In fact, with so much blues, R&B, and rock and roll rising from the South in the 1950s, this region regained some of its cultural flavor, which (along with a sizable portion of the population) had migrated to the North after the Civil War and during the early twentieth century. Meanwhile, musicians and audiences in the North had absorbed blues music as their own, eliminating the understanding of blues as a specifically southern style. Like the many white teens today who are fascinated by hip-

But the key to record sales and the spread of rock and roll, according to famed record producer Sam Phillips of Sun Records, was to find a white man who sounded black. Phillips found that man in Elvis Presley. Commenting on Presley’s cultural importance, one critic wrote: “White rockabillies like Elvis took poor white southern mannerisms of speech and behavior deeper into mainstream culture than they had ever been taken.”21

The Sacred and the Secular

Although many mainstream adults in the 1950s complained that rock and roll’s sexuality and questioning of moral norms constituted an offense against God, in fact many early rock figures had close ties to religion. Jerry Lee Lewis attended a Bible institute in Texas (although he was eventually thrown out); Ray Charles converted an old gospel tune he had first heard in church as a youth into “I Got a Woman,” one of his signature songs; and many other artists transformed gospel songs into rock and roll.

Still, many people did not appreciate the blurring of boundaries between the sacred and the secular. In the late 1950s, public outrage over rock and roll was so great that even Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis, both sons of southern preachers, became convinced that they were playing the “devil’s music.” By 1959, Little Richard had left rock and roll to become a minister. Lewis had to be coerced into recording “Great Balls of Fire,” a song by Otis Blackwell that turned an apocalyptic biblical phrase into a sexually charged teen love song that was banned by many radio stations but nevertheless climbed to No. 2 on the pop charts in 1957. The boundaries between sacred and secular music have continued to blur in the years since, with some churches using rock and roll to appeal to youth, and some Christian-

Battles in Rock and Roll

The blurring of racial lines and the breakdown of other conventional boundaries meant that performers and producers were forced to play a tricky game to get rock and roll accepted by the masses. Two prominent white disc jockeys used different methods. Cleveland deejay Alan Freed, credited with popularizing the term rock and roll, played original R&B recordings from the race charts and black versions of early rock and roll on his program. In contrast, Philadelphia deejay Dick Clark believed that making black music acceptable to white audiences required cover versions by white artists. By the mid-

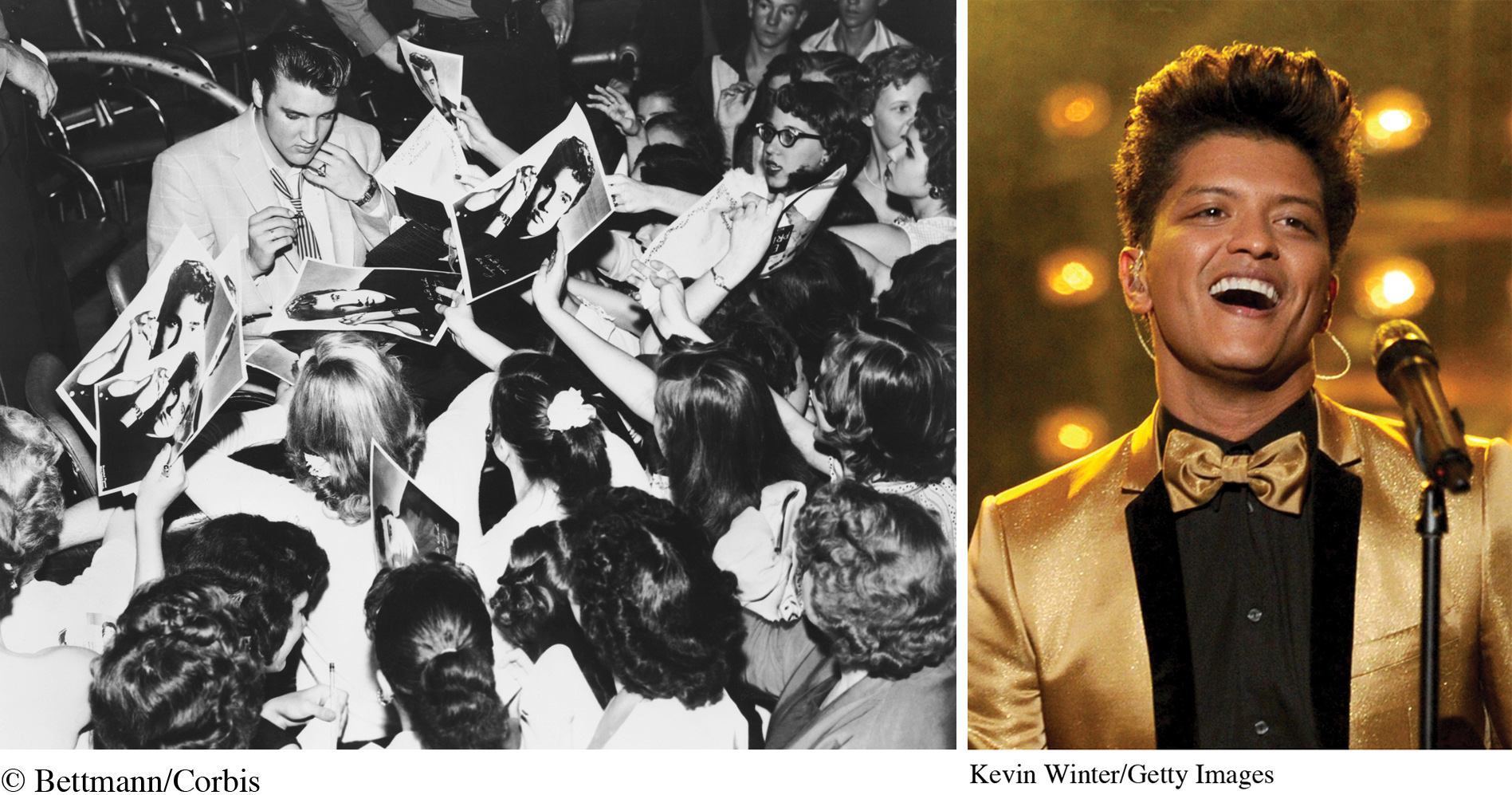

ELVIS PRESLEY AND HIS LEGACY Elvis Presley remains the most popular solo artist of all time. From 1956 to 1962, he recorded seventeen No. 1 hits, from “Heartbreak Hotel” to “Good Luck Charm.” According to Little Richard, Presley’s main legacy was that he opened doors for many young performers and made black music popular in mainstream America. Presley’s influence continues to be felt today in the music of artists such as Bruno Mars.

White Cover Music Undermines Black Artists

By the mid-

Although today we take such rerecordings for granted, in the 1950s the covering of black artists’ songs by white musicians was almost always an attempt to capitalize on popular songs from the R&B “race” charts by transforming them into hits on the white pop charts. Often, not only would white producers give cowriting credit to white performers for the tunes they merely covered, but the producers would also buy the rights to potential hits from black songwriters, who seldom saw a penny in royalties or received songwriting credit.

During this period, black R&B artists, working for small record labels, saw many of their popular songs covered by white artists working for major labels. These cover records, boosted by better marketing and ties to white deejays, usually outsold the original black versions. For instance, the 1954 R&B song “Sh-

Overt racism lingered in the music business well into the 1960s. A turning point, however, came in 1962, the last year that Pat Boone, then aged twenty-

Payola Scandals Tarnish Rock and Roll

The payola scandals of the 1950s were another cloud over rock-

Although payola was considered a form of bribery, no laws prohibited its practice. However, following closely on the heels of television’s quiz-

The payola scandals threatened, ended, or damaged the careers of a number of rock-

Fears of Corruption Lead to Censorship

Since rock and roll’s inception, one of the uphill battles the genre faced was the perception that it was a cause of juvenile delinquency, which was statistically on the rise in the 1950s. Looking for an easy culprit rather than considering contributing factors such as neglect, the rising consumer culture, or the growing youth population, many assigned blame to rock and roll. The view that rock and roll corrupted youth was widely accepted by social authorities, and rock-

By late 1959, many key figures in rock and roll had been tamed. Jerry Lee Lewis was exiled from the industry, labeled southern “white trash” for marrying his thirteen-

Although rock and roll did not die in the late 1950s, the U.S. recording industry decided that it needed a makeover. To protect the enormous profits the new music had been generating, record companies began to discipline some of rock and roll’s rebellious impulses. In the early 1960s, the industry introduced a new generation of clean-