The Sounds of Commercial Radio

Contemporary radio sounds very different from its predecessor. In contrast to the few stations per market in the 1930s, most large markets today include more than forty stations that vie for listener loyalty. With the exception of national network–sponsored news segments and nationally syndicated programs, most programming is locally produced and heavily dependent on the music industry for content. Although a few radio personalities—

However, listeners today are unlike radio’s first audiences in several ways. First, listeners in the 1930s tuned in to their favorite shows at set times. Listeners today do not say, “Gee, my favorite song is coming on at 8 P.M., so I’d better be home to listen.” Instead, radio has become a secondary, or background, medium that follows the rhythms of daily life. Radio programmers today worry about channel cruising—

Second, in the 1930s, peak listening time occurred during the evening hours—

Third, stations today are more specialized. Listeners are loyal to favorite stations, music formats, and even radio personalities, rather than to specific shows. People generally listen to only four or five stations that target them. More than fifteen thousand radio stations now operate in the United States, customizing their sounds to reach niche audiences through format specialization and alternative programming.

Format Specialization

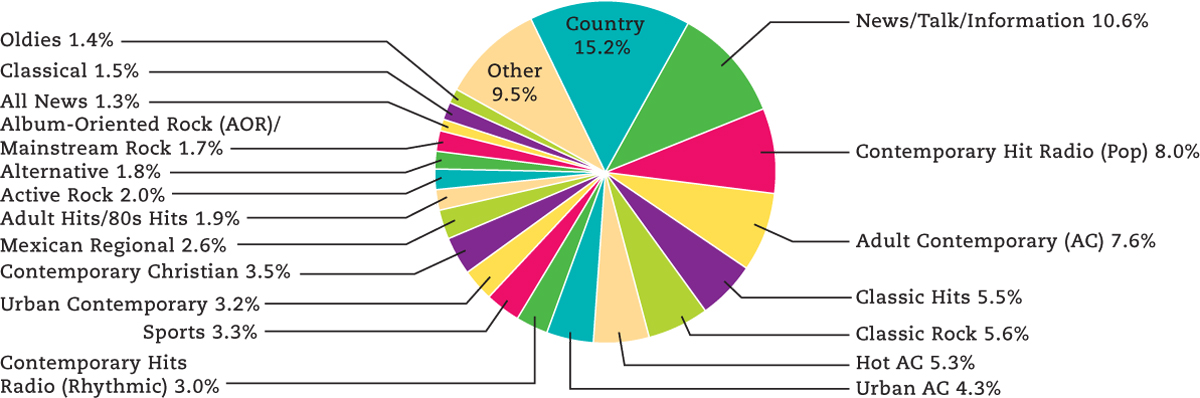

Stations today use a variety of formats based on managed program logs and day parts. All told, more than forty different radio formats, plus variations, serve diverse groups of listeners (see Figure 5.4). To please advertisers, who want to know exactly who is listening, formats usually target audiences according to their age, income, gender, or race/ethnicity. Radio’s specialization enables advertisers to reach smaller target audiences at costs that are much lower than those for television.

FIGURE 5.4THE MOST POPULAR RADIO FORMATS IN THE UNITED STATES AMONG PERSONS AGE TWELVE AND OLDERData from: Nielsen report: “State of the Media: Audio Today 2015, How America Listens,” March 5, 2015, www.nielsen.com/

Targeting listeners has become extremely competitive, however, because forty or fifty stations may be available in a large radio market. About 10 percent of all stations across the country switch formats each year in an effort to find a formula that generates more advertising money. Some stations, particularly those in large cities, even rent blocks of time to various local ethnic or civic groups; this enables the groups to dictate their own formats and sell ads.

News, Talk, and Information Radio

The nation’s fastest-

| Talk Show Host | 2003 | 2008 | 2015 |

| Rush Limbaugh (Conservative) | 14.5 | 14.25 | 13.25 |

| Sean Hannity (Conservative) | 11.75 | 13.25 | 12.50 |

| Dave Ramsey (Financial Advice) | * | 4.5 | 8.25 |

| Glenn Beck (Conservative) | * | 6.75 | 7 |

| Mark Levin (Conservative) | N/A | 5.5 | 7 |

| Michael Savage (Conservative) | 7 | 8.25 | 5.25 |

| Jim Bohannon (Moderate) | 4 | 3.5 | 2.75 |

Table 5.2: TABLE 5.2 TALK RADIO WEEKLY AUDIENCE (IN MILLIONS)Data from: Talkers magazine, “The Top Talk Radio Audiences,” October 2015.Note:* = Information unavailable; N/A = Talk host not nationally broadcast.

CASE STUDY

Host: The Origins of Talk Radio

by David Foster Wallace

T he origins of contemporary political talk radio can be traced to three phenomena of the 1980s. The first of these involved AM music stations getting absolutely murdered by FM, which could broadcast music in stereo and allowed for much better fidelity on high and low notes. The human voice, on the other hand, is midrange and doesn’t require high fidelity. The eighties’ proliferation of talk formats on the AM band also provided new careers for some music deejays—

GLENN BECK is the conservative host of The Glenn Beck Program, a nationally syndicated talk-

The second big factor was the repeal, late in Ronald Reagan’s second term, of what was known as the Fairness Doctrine. This was a 1949 FCC rule designed to minimize any possible restrictions on free speech caused by limited access to broadcasting outlets. The idea was that, as one of the conditions for receiving an FCC broadcast license, a station had to “devote reasonable attention to the coverage of controversial issues of public importance,” and consequently had to provide “reasonable, although not necessarily equal,” opportunities for opposing sides to express their views. Because of the Fairness Doctrine, talk stations had to hire and program symmetrically: If you had a three-

The Fairness Doctrine’s repeal was part of the sweeping deregulations of the Reagan era, which aimed to liberate all sorts of industries from government interference and allow them to compete freely in the marketplace. The old, Rooseveltian logic of the Doctrine had been that since the airwaves belonged to everyone, a license to profit from those airwaves conferred on the broadcast industry some special obligation to serve the public interest. Commercial radio broadcasting was not, in other words, originally conceived as just another for-

More or less on the heels of the Fairness Doctrine’s repeal came the West Coast and then national syndication of The Rush Limbaugh Show through Mr. McLaughlin’s EFM Media. Limbaugh is the third great progenitor of today’s political talk radio partly because he’s a host of extraordinary, once-

Source: Excerpted from David Foster Wallace, “Host: The Origins of Talk Radio,” Atlantic, April 2005, pp. 66–68.

Music Formats

WENDY WILLIAMS refers to herself as the “Queen of All Media,” but before her daytime TV talk show, she got her start with a nearly two-

The adult contemporary (AC) format, also known as middle-

Country is the most popular format in the nation (except during morning drive time, when news/talk/information is number one). Many stations are in tiny markets where country is traditionally the default format for communities with only one radio station. Country music has old roots in radio, starting in 1925 with the influential Grand Ole Opry program on WSM in Nashville. Although Top 40 drove country music out of many radio markets in the 1950s, the growth of FM in the 1960s brought it back, as station managers looked for market niches not served by rock music.

Many formats appeal to particular ethnic or racial groups. In 1947, WDIA in Memphis was the first station to program exclusively for black listeners. Now called urban contemporary, this format targets a wide variety of African American listeners, primarily in large cities. Urban contemporary, which typically plays popular dance, rap, R&B, and hip-

Spanish-

In addition, today there are other formats that are spin-

EL ZOL 106.7 is a top Spanish-

Research indicates that most people identify closely with the music they listened to as adolescents and young adults. This tendency partially explains why classic hits and classic rock stations combined have surpassed CHR stations today. It also helps explain the recent nostalgia for music from the 1980s and 1990s.

Nonprofit Radio and NPR

PUBLIC RADIO STATIONS in rural areas, like WMMT—

Although commercial radio (particularly those stations owned by huge radio conglomerates) dominates the radio spectrum, nonprofit radio maintains a voice. But the road to viability for nonprofit radio in the United States has not been easy. In the 1930s, the Wagner-

The Early Years of Nonprofit Radio

Two government rulings, both in 1948, aided nonprofit radio. First, the government began authorizing noncommercial licenses to stations not affiliated with labor, religious, education, or civic groups. The first license went to Lewis Kimball Hill, a radio reporter and pacifist during World War II who started the Pacifica Foundation to run experimental public stations. Pacifica stations, like Hill, have often challenged the status quo in radio as well as in government. Most notably, in the 1950s they aired the poetry, prose, and music of performers considered radical, left-

Second, the FCC approved 10-

Creation of the First Noncommercial Networks

During the 1960s, nonprofit broadcasting found a Congress sympathetic to an old idea: using radio and television as educational tools. As a result, National Public Radio (NPR) and the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) were created as the first noncommercial networks. Under the provisions of the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967 and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), NPR and PBS were mandated to provide alternatives to commercial broadcasting. Now, NPR’s popular news and interview programs, such as Morning Edition and All Things Considered, are thriving, and they contribute to the network’s audience of thirty-

Over the years, however, public radio has faced waning government support and the threat of losing its federal funding. In 1994, a conservative majority in Congress cut financial support and threatened to scrap the CPB, the funding authority for public broadcasting. In 2011, the House voted to end financing for the CPB, but the Senate voted against the measure. Consequently, stations have become more reliant on private donations and corporate sponsorship, which could cause some public broadcasters to steer clear of controversial subjects, especially those that critically examine corporations (see “Media Literacy and the Critical Process: Comparing Commercial and Noncommercial Radio” above).

Like commercial stations, nonprofit radio has adopted the format style. However, the dominant style in public radio is a loose variety format whereby a station may actually switch from jazz, classical music, and alternative rock to news and talk during different parts of the day. Noncommercial radio remains the place for both tradition and experimentation, as well as for programs that do not draw enough listeners for commercial success.

Media Literacy and the Critical Process

Comparing Commercial and Noncommercial Radio

After the arrival and growth of commercial TV, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB) was created in 1967 as the funding agent for public broadcasting—

1 DESCRIPTION. Listen to a typical morning or late-

2 ANALYSIS. Look for patterns. What kinds of stories are covered? What kinds of topics are discussed? Create a chart to categorize the stories. To cover events and issues, do the stations use actual reporters at the scene? How much time is given to reporting compared to time devoted to opinion? How many sources are cited in each story? What kinds of interview sources are used? Are they expert sources or regular person-

3 INTERPRETATION. What do these patterns mean? Is there a balance between reporting and opinion? Do you detect any bias, and if so, how did you determine this? Are the stations serving as watchdogs to ensure that democracy’s best interests are being served? What effect, if any, do you think the advertisers/supporters have on the programming? What arguments might you make about commercial and noncommercial radio based on your findings?

4 EVALUATION. Which station seems to be doing a better job serving its local audience? Why? Do you buy the 1930s argument that noncommercial stations serve narrow, special interests while commercial stations serve capitalism and the public interest? Why or why not? From which station did you learn the most, and which station did you find most entertaining? Explain. What did you like and dislike about each station?

5 ENGAGEMENT. Join your college radio station. Talk to the station manager about the goals for a typical hour of programming and what audience the station is trying to reach. Finally, pitch program or topic ideas that would improve your college station’s programming.

New Radio Technologies Offer More Stations

LaunchPad

Going Visual: Video, Radio, and the Web This video looks at how radio stations adapted to the Internet by providing multimedia on their Web sites to attract online listeners.

Discussion: If video is now important to radio, what might that mean for journalism and broadcasting students who are considering a job in radio?

Over the past decade or so, two alternative radio technologies have helped expand radio beyond its traditional AM and FM bands and bring more diverse sounds to listeners: satellite and HD (digital) radio.

Satellite Radio

A series of satellites launched to cover the continental United States created a subscription-

Programming includes a range of music channels, from rock and reggae to Spanish Top 40 and opera, as well as channels dedicated to NASCAR, NPR, cooking, and comedy. Another feature of satellite radio’s programming is popular personalities who host their own shows or have their own channels, including Howard Stern, Martha Stewart, Oprah Winfrey, and Bruce Springsteen. U.S. automakers (investors in the satellite radio companies) now equip most new cars with a satellite band, in addition to AM and FM, in order to promote further adoption of satellite radio. SiriusXM had more than twenty-

HD Radio

Available to the public since 2004, HD radio is a digital technology that enables AM and FM radio broadcasters to multicast up to three additional compressed digital signals within their traditional analog frequency. For example, KNOW, a public radio station at 91.1 FM in Minneapolis–St. Paul, runs its National Public Radio news/talk/information format on 91.1 HD1, runs Radio Heartland (acoustic and Americana music) on 91.1 HD2, and runs the BBC News service on 91.1 HD3. About 2,200 radio stations now broadcast in HD. To tune in, listeners need a radio with the HD band, which brings in CD-

Radio and Convergence

Like every other mass medium, radio is moving into the future by converging with the Internet. Interestingly, this convergence is taking radio back to its roots in some aspects. Internet radio allows for much more variety in radio, which is reminiscent of radio’s earliest years, when nearly any individual or group with some technical skill could start a radio station. Moreover, podcasts bring back such content as storytelling, instructional programs, and local topics of interest, which have largely been missing in corporate radio. And portable listening devices like the iPod and radio apps for the iPad and smartphones hark back to the compact portability that first came with the popularization of transistor radios in the 1950s.

Internet Radio

Internet radio emerged in the 1990s with the popularity of the Web. Internet radio stations come in two types. The first involves an existing AM, FM, satellite, or HD station “streaming” a simulcast version of its on-

Beginning in 2002, a Copyright Royalty Board established by the Library of Congress began to assess royalty fees for streaming copyrighted songs over the Internet based on a percentage of each station’s revenue. Webcasters complained that royalty rates set by the board were too high and threatened their financial viability, particularly compared to satellite radio, which pays a lower royalty rate, and broadcasters, who pay no royalty rates at all. For decades, radio broadcasters have paid mechanical royalties to songwriters and music publishers but no royalties to the performing artists or record companies. Broadcasters have argued that the promotional value of getting songs played is sufficient compensation.

In 2009, Congress passed the Webcaster Settlement Act, which was considered a lifeline for Internet radio. The act enabled Internet stations to negotiate royalty fees directly with the music industry, at rates presumably more reasonable than what the Copyright Royalty Board had proposed. In 2012, Clear Channel became the first company to strike a deal directly with the recording industry. Clear Channel (now iHeartMedia) pledged to pay royalties to Big Machine Label Group—

Clear Channel’s deal with the music industry opened up new dialogue about equalizing the royalty rates paid by broadcast radio, satellite radio, and Internet radio. Tim Westergren, founder of Pandora, argued before Congress in 2012 that the rates were most unfair to companies like his. In the previous year, Westergren said, Pandora paid 50 percent of its revenue for performance royalties, whereas satellite radio service SiriusXM paid 7.5 percent of its revenue for performance royalties, and broadcast radio paid nothing. He noted that a car equipped with an AM/FM radio, satellite radio, and streaming Internet radio could deliver the same song to a listener through all three technologies, but the various radio services would pay markedly different levels of performance royalties to the artist and record company.17

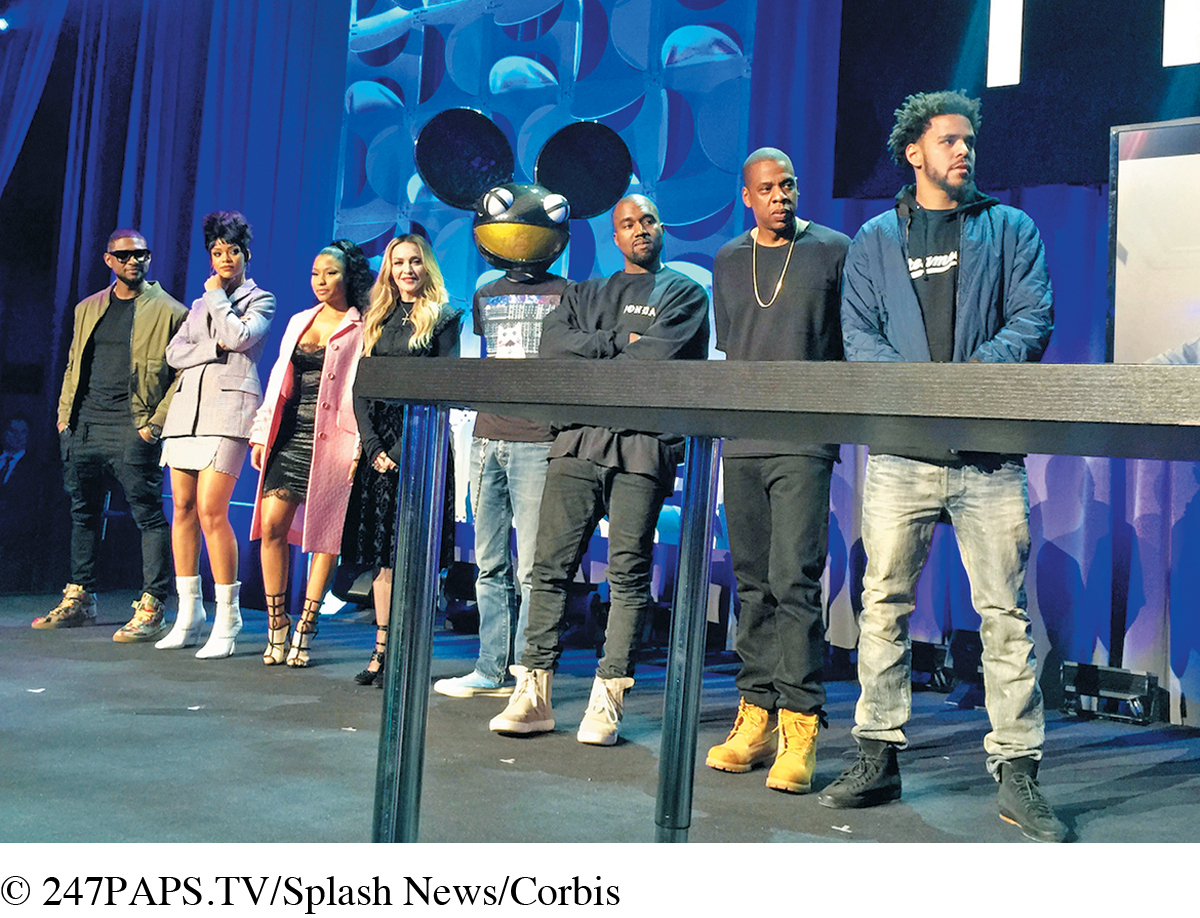

TIDAL, a high-

GLOBAL VILLAGE

Radio Goes Local, Global, and Local Again

S ince the 1950s, radio has focused on music content and its local connection to its audience. Local deejays personally connected with their listeners, introduced them to new music, and encouraged them to call in with song requests. Local stations also took their shows into the community, with live broadcasts from local festivals and events or from an advertiser (such as a local car dealership) that wanted its weekend sale to sound like an event.

Two things in the 1990s changed all of that. First, federal deregulation enabled small chains of stations to grow into enormous cross-

Small stations started streaming their live broadcasts, and as computer connections got faster, more and more listeners from around the world logged in. Local went global; even the tiniest stations could have international listeners, who might also financially support the local station. For example, KQNY 91.9 FM—

At the same time, Internet-

All of this has made for a rich global radio listening environment. The London-

The biggest recent entry to the global radio business is Apple. As the company’s iTunes music download business has been declining, it has pinned its hopes for the future on Apple Music, a subscription-

The newspaper the Australian forecasts the possible end of local radio with Apple’s “global radio station.” “If you don’t like the offerings of terrestrial broadcasters, or the satellite-

But executives of old-

Podcasting and Portable Listening

Developed in 2004, podcasting (the term marries iPod and broadcasting) refers to the practice of making audio files available on the Internet so listeners can download them onto their computers and either transfer them to portable MP3 players or listen to the files on the computer. This distribution method quickly became mainstream, as mass media companies created commercial podcasts to promote and extend existing content, such as news and reality TV, while independent producers developed new programs, such as public radio’s Serial, a popular weekly audio nonfiction narrative.

Podcasts have led the way for people to listen to radio on mobile devices like smartphones. Satellite radio, Internet-

For the broadcast radio industry, portability used to mean listening on a transistor or car radio. But with the digital turn to iPods and mobile phones, broadcasters haven’t been as easily available on today’s primary portable audio devices. Hoping to change that, the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) has been lobbying the FCC and the mobile phone industry to include FM radio capability in all mobile phones. New mobile phones in the United States now have FM radio chips, but Sprint is the only major cell phone company to enable the chips with the NextRadio app.18 Although the NAB argues that the enabled radio chip would be most important for enabling listeners to access local broadcast radio in times of emergencies and disasters, the chip would also be commercially beneficial for radio broadcasters, putting them on the same digital devices as their nonbroadcast radio competitors, like Pandora.