The Studio System’s Golden Age

Many consider Hollywood’s Golden Age as beginning in 1915 with innovations in feature-

Hollywood Narrative and the Silent Era

A SILENT COMEBACK The Artist, a tribute to silent movies set around the dawn of the talkies, won the Academy Award for best picture of 2011. It was the first (mostly) silent movie to win since the first Academy Awards in 1927.

D. W. Griffith, among the first “star” directors, was the single most important director in Hollywood’s early days. Griffith paved the way for all future narrative filmmakers by refining many of the narrative techniques introduced by Méliès and Porter and using nearly all of them in one film for the first time, including varied camera distances, close-

Feature films became the standard throughout the 1920s and introduced many of the film genres we continue to see produced today. The most popular films during the silent era were historical and religious epics, including Napoleon (1927), Ben-

The Introduction of Sound

With the studio system and Hollywood’s worldwide dominance firmly in place, the next big challenge was to bring sound to moving pictures. Various attempts at talkies had failed since Edison first tried to link phonograph and moving picture technologies in the 1890s. During the 1910s, however, technical breakthroughs at AT&T’s research arm, Bell Labs, produced prototypes of loudspeakers and sound amplifiers. Experiments with sound continued during the 1920s, particularly at Warner Brothers studios, which released numerous short sound films of vaudeville acts, featuring singers and comedians. The studio packaged them as a novelty along with silent feature films.

In 1927, Warner Brothers produced The Jazz Singer, a feature-

Warner Brothers, however, was not the only studio exploring sound technology. Five months before The Jazz Singer opened, Fox studio premiered sound-

Boosted by the innovation of sound, annual movie attendance in the United States rose from sixty million a week in 1927 to ninety million a week in 1929. By 1931, nearly 85 percent of America’s twenty thousand theaters accommodated sound pictures; and by 1935, the world had adopted talking films as the commercial standard.

The Development of the Hollywood Style

By the time sound came to movies, Hollywood dictated not only the business but also the style of most moviemaking worldwide. That style, or model, for storytelling developed with the rise of the studio system in the 1920s, solidified during the first two decades of the sound era, and continues to dominate American filmmaking today. The model serves up three ingredients that give Hollywood movies their distinctive flavor: the narrative, the genre, and the author (or director). The right blend of these ingredients—

Hollywood Narratives

American filmmakers from D. W. Griffith to Steven Spielberg have understood the allure of narrative, which always includes two basic components: the story (what happens to whom) and the discourse (how the story is told). Further, Hollywood codified a familiar narrative structure across all genres. Most movies, like most TV shows and novels, feature recognizable character types (protagonist, antagonist, romantic interest, sidekick); a clear beginning, middle, and end (even with flashbacks and flash-

Within Hollywood’s classic narratives, filmgoers find an amazing array of intriguing cultural variations. For example, familiar narrative conventions of heroes, villains, conflicts, and resolutions may be made more unique with inventions like computer-

Hollywood Genres

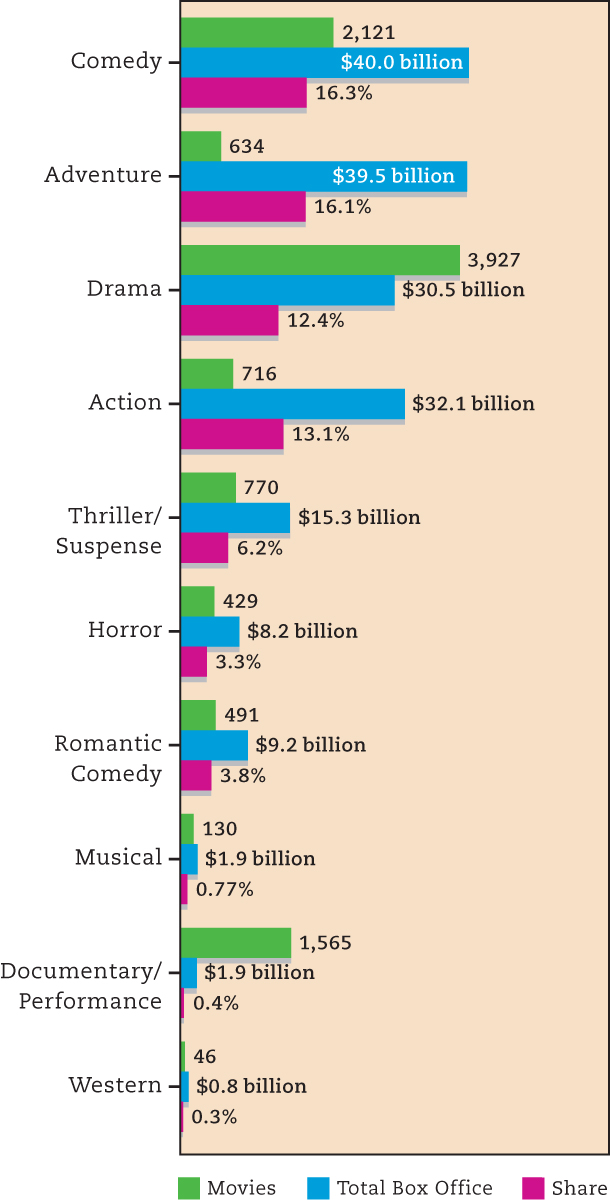

TABLE 7.1 HOLLYWOOD’S TOP GENRES Data from: “Market Share for Each Genre 1995–2015,” The Numbers, June 24, 2015, www.the-numbers.com/

In general, Hollywood narratives fit a genre, or category, in which conventions regarding similar characters, scenes, structures, and themes recur in combination. (See Table 7.1 for a list of Hollywood’s top movie genres.) Grouping films by category is another way for the industry to achieve the two related economic goals of product standardization and product differentiation. By making films that fall into popular genres, the movie industry provides familiar models that can be imitated. It is much easier for a studio to promote a film that already fits into a preexisting category with which viewers are familiar. Among the most familiar genres are comedy, adventure, drama, action, thriller/suspense, horror, romantic comedy, musical, documentary/performance, western, gangster, fantasy–science fiction, and film noir.

Variations of dramas and comedies have long dominated film’s narrative history. A western typically features “good” cowboys battling “evil” bad guys, as in True Grit (2010), or resolves tension between the natural forces of the wilderness and the civilizing influence of a town. Romances (such as The Fault in Our Stars, 2014) present conflicts that are mediated by the ideal of love. Another popular genre, thriller/suspense (such as Prisoners, 2013), usually casts “the city” as a corrupting place that needs to be overcome by the moral courage of a heroic detective.10

Because most Hollywood narratives try to create believable worlds, the artificial style of musicals is sometimes a disruption of what many viewers expect. Musicals’ popularity peaked in the 1940s and 1950s, but they showed a small resurgence in the 2000s with Moulin Rouge! (2001), Chicago (2002), and Les Misérables (2012). Still, no live-

Another fascinating genre is the horror film, which also claims none of the top fifty highest-

The film noir genre (French for “black film”) developed in the United States in the late 1920s and hit its peak after World War II. Still, the genre continues to influence movies today. Using low-

Hollywood “Authors”

In commercial filmmaking, the director serves as the main author of a film. Sometimes called “auteurs,” successful directors develop a particular cinematic style or an interest in particular topics that differentiates their narratives from those of other directors. Alfred Hitchcock, for instance, redefined the suspense drama through editing techniques that heightened tension (Rear Window, 1954; Vertigo, 1958; North by Northwest, 1959; Psycho, 1960).

FILM GENRES Psycho (1960), a classic horror film, tells the story of Marion Crane (played by Janet Leigh), who flees to a motel after embezzling $40,000 from her employer. There, she meets the motel owner, Norman Bates (played by Anthony Perkins), and her untimely death. The infamous shower scene, pictured above, is widely considered one of the most iconic horror film sequences.

The contemporary status of directors stems from two breakthrough films: Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider (1969) and George Lucas’s American Graffiti (1973), which became surprise box-

This opened the door for a new wave of directors who were trained in California or New York film schools and were also products of the 1960s, such as Francis Ford Coppola (The Godfather, 1972), William Friedkin (The Exorcist, 1973), Steven Spielberg (Jaws, 1975), Martin Scorsese (Taxi Driver, 1976), Brian De Palma (Carrie, 1976), and George Lucas (Star Wars, 1977). Combining news or documentary techniques and Hollywood narratives, these films demonstrated how mass media borders had become blurred and how movies had become dependent on audiences who were used to television and rock and roll. These films signaled the start of a period that Scorsese has called “the deification of the director.” A handful of successful directors gained the kind of economic clout and celebrity standing that had belonged almost exclusively to top movie stars.

Although the status of directors grew in the 1960s and 1970s, recognition for women directors of Hollywood features remained rare.11 A breakthrough came with Kathryn Bigelow’s best director Academy Award for The Hurt Locker (2009), which also won the best picture award. Prior to Bigelow’s win, only three women had received an Academy Award nomination for directing a feature film: Lina Wertmüller in 1976 for Seven Beauties, Jane Campion in 1994 for The Piano, and Sofia Coppola in 2004 for Lost in Translation. Both Wertmüller and Campion are from outside the United States, where women directors frequently receive more opportunities for film development. Some women in the United States get an opportunity to direct because of their prominent standing as popular actors; Barbra Streisand, Jodie Foster, Penny Marshall, and Sally Field all fall into this category. Other women have come to direct films via their scriptwriting achievements. For example, Jennifer Lee, who wrote Wreck-

Members of minority groups, including African Americans, Asian Americans, and Native Americans, have also struggled for recognition in Hollywood. Still, some have succeeded as directors, crossing over from careers as actors or gaining notoriety through independent filmmaking. Among the most successful contemporary African American directors are Kasi Lemmons (Black Nativity, 2013), Lee Daniels (The Butler, 2013), John Singleton (Abduction, 2011), Tyler Perry (A Madea Christmas, 2013), and Spike Lee (Oldboy, 2013). (See “Case Study: Breaking through Hollywood’s Race Barrier” on page 247.) Asian Americans such as M. Night Shyamalan (After Earth, 2013), Ang Lee (Life of Pi, 2012), Wayne Wang (Snow Flower and the Secret Fan, 2011), and documentarian Arthur Dong (The Killing Fields of Dr. Haing S. Ngor, 2014) have built immensely accomplished directing careers. Chris Eyre (Hide Away, 2011) remains the most noted Native American director, working mainly as an independent filmmaker.

WOMEN DIRECTORS have long struggled in Hollywood. However, some, like Kathryn Bigelow and Ava DuVernay are making a name for themselves. Known for her rough-

Outside the Hollywood System

Since the rise of the studio system, Hollywood has focused on feature-

Global Cinema

For generations, Hollywood has dominated the global movie scene. In many countries, American films capture up to 90 percent of the market. In striking contrast, foreign films constitute only a tiny fraction—

Early on, Americans showed interest in British and French short films and in experimental films, such as Germany’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919). Foreign-

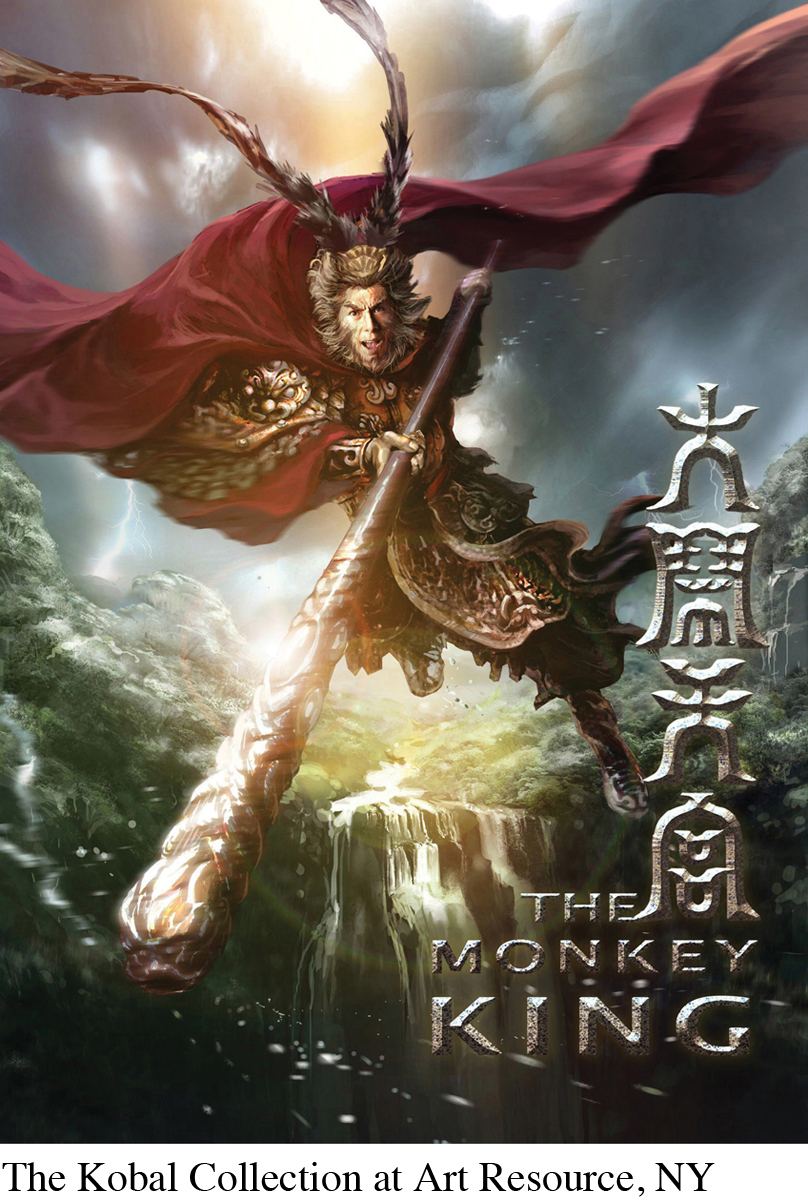

FOREIGN FILMS China restricts the number of imported films shown and regulates the lengths of their runs in order to protect its own domestic film industry. Nonetheless, China has become a lucrative market—

Postwar prosperity, rising globalism, and the gradual decline of the studios’ hold over theater exhibition in the 1950s and 1960s stimulated the rise of art-

By the late 1970s, though, the home video market had emerged, and audiences began staying home to watch both foreign and domestic films. New multiplex theater owners rejected the smaller profit margins of most foreign titles, which lacked the promotional hype of U.S. films. As a result, between 1966 and 1990 the number of foreign films released annually in the United States dropped by two-

With the growth of superstore video chains like Blockbuster in the 1990s, which were supplanted by online video services like Netflix in the 2000s, viewers gained access to a larger selection of foreign-

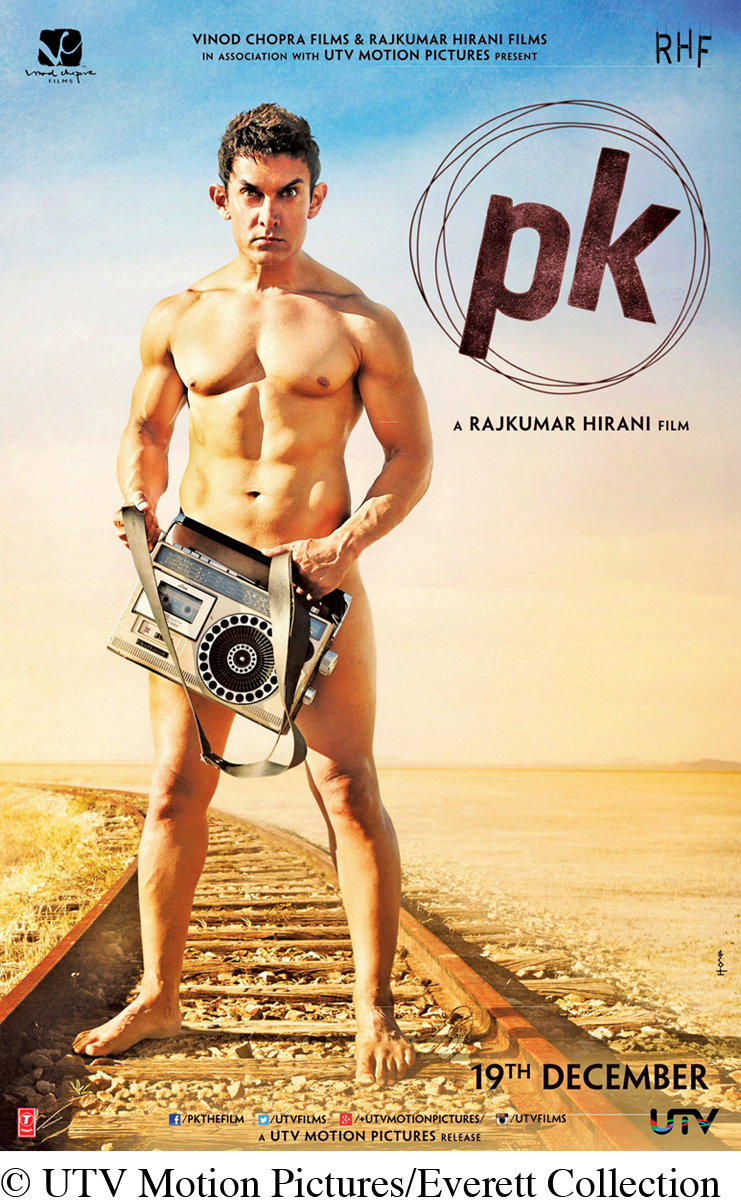

Today, the largest film industry is in India, out of Bollywood (a play on words combining city names Bombay—

CASE STUDY

Breaking through Hollywood’s Race Barrier

T he problem of the term black cinema is that such a term needs to exist. (Do we, for example, talk about a white cinema in the United States?) But there is a long history of blacks’ exclusion from the industry as writers, directors, and actors—

Despite African Americans’ long support of the film industry, their moviegoing experience has not been the same as that of whites. From the late 1800s until the passage of Civil Rights legislation in the mid-

Changes began taking place during and after World War II. In response to the “white flight” from central cities during the suburbanization of the 1950s, many downtown and neighborhood theaters began catering to black customers in order to keep from going out of business. By the late 1960s and early 1970s, these theaters had become major venues for popular commercial films, even featuring a few movies about African Americans, including Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? (1967), In the Heat of the Night (1967), The Learning Tree (1969), and Sounder (1972).

Based on the popularity of these films, black photographer-

Opportunities for black film directors have expanded some since the 1980s and 1990s, but only recently have black filmmakers achieved a measure of mainstream success. Lee Daniels received only the second Academy Award nomination for a black director for Precious: Based on the Novel “Push” by Sapphire in 2009 (the first was John Singleton for Boyz N the Hood in 1991). Precious, about an obese, illiterate black teenage girl subjected to severe sexual and emotional abuse, was praised by many critics but decried by others who interpreted it as either more blaxploitation or “poverty porn.”2 In 2013, Daniels returned as the director of The Butler, inspired by the true story of an African American man who experienced major events of the twentieth century from his position as a White House butler. In that same year, 12 Years a Slave—a film by black British director Steve McQueen—

The Documentary Tradition

Both TV news and nonfiction films trace their roots to the movie industry’s interest films and newsreels of the late 1890s. In Britain, interest films compiled footage of regional wars, political leaders, industrial workers, and agricultural scenes, and were screened with fiction shorts. Pioneered in France and England, newsreels consisted of weekly ten-

Early filmmakers also produced travelogues, which recorded daily life in various communities around the world. Travel films reached a new status in Robert Flaherty’s classic Nanook of the North (1922), which tracked an Inuit family in the harsh Hudson Bay region of Canada. Flaherty edited his fifty-

Over time, the documentary developed an identity apart from its commercial presentation. As an educational, noncommercial form, the documentary usually required the backing of industry, government, or philanthropy to cover costs. In support of a clear alternative to Hollywood cinema, some nations began creating special units, such as Canada’s National Film Board, to sponsor documentaries. In the United States, art and film received considerable support from the Roosevelt administration during the Depression.

By the late 1950s and early 1960s, the development of portable cameras had led to cinema verité (a French term for “truth film”). This documentary style allowed filmmakers to go where cameras could not go before and record fragments of everyday life more unobtrusively. Directly opposed to packaged, high-

Perhaps the major contribution of documentaries has been their willingness to tackle controversial or unpopular subject matter. For example, American documentary filmmaker Michael Moore often addresses complex topics that target corporations or the government. His films include Roger and Me (1989), a comic and controversial look at the relationship between the city of Flint, Michigan, and General Motors; the Oscar-

DOCUMENTARY FILMS Citizenfour, a documentary released in 2014, tells the story of Edward Snowden—

The Rise of Independent Films

The success of documentary films like Super Size Me and Fahrenheit 9/11 dovetails with the rise of indies, or independently produced films. As opposed to directors working in the Hollywood system, independent filmmakers typically operate on a shoestring budget and show their movies in thousands of campus auditoriums and at hundreds of small film festivals. The decreasing costs of portable technology, including smaller digital cameras and computer editing, have kept many documentary and independent filmmakers in business. They make movies inexpensively, relying on real-

Distributing smaller films can be big business for the studios. The rise of independent film festivals in the 1990s—

But by 2010, the independent film business as a feeder system for major studios was declining due to the poor economy and studios’ waning interest in smaller specialty films. Disney sold Miramax for $660 million to an investor group composed of Hollywood outsiders. Viacom folded its independent unit, Paramount Vantage, into its main studio, and Time Warner closed its Warner Independent and Picturehouse in-

INDEPENDENT FILM FESTIVALS, like the Sundance Film Festival, are widely recognized in the film industry as a major place to discover new talent and acquire independently made films on topics that might otherwise be too controversial, too niche specific, or too original for a major studio-

GLOBAL VILLAGE

Beyond Hollywood: Asian Cinema

A sian nations easily outstrip Hollywood in quantity of films produced. India alone produces about a thousand movies a year. But from India to South Korea, Asian films are increasingly challenging Hollywood in terms of quality, and they have become more influential as Asian directors, actors, and film styles are exported to Hollywood and the world.

India

The current highest-

Part musical, part action, part romance, and part suspense, the epic films of Bollywood typically have fantastic sets, hordes of extras, plenty of wet saris, and symbolic fountain bursts (as a substitute for kissing and sex, which are prohibited from being shown). Indian movie fans pay from $.75 to $5 to see these films, and they feel shortchanged if the movies are shorter than three hours. With many films produced in less than a week, however, most of the Bollywood fare is cheaply produced and badly acted. But these production aesthetics are changing, as bigger-

China

Since the late 1980s, Chinese cinema has developed an international reputation. Leading this generation of directors are Yimou Zhang (House of Flying Daggers, 2004; Coming Home, 2014) and Kaige Chen (Farewell My Concubine, 1993; Caught in the Web, 2012), whose work has spanned such genres as historical epics, love stories, contemporary tales of city life, and action fantasy. These directors have also helped make international stars out of Li Gong (Memoirs of a Geisha, 2005; Coming Home, 2014) and Ziyi Zhang (Memoirs of a Geisha, 2005; Dangerous Liaisons, 2012).

Hong Kong

Hong Kong films were the most talked about—

Japan

Americans may be most familiar with low-

South Korea

The end of military regimes in the late 1980s and corporate investment in the film business in the 1990s created a new era in Korean moviemaking. Leading directors include Kim Jee-