The Development of Modern American Magazines

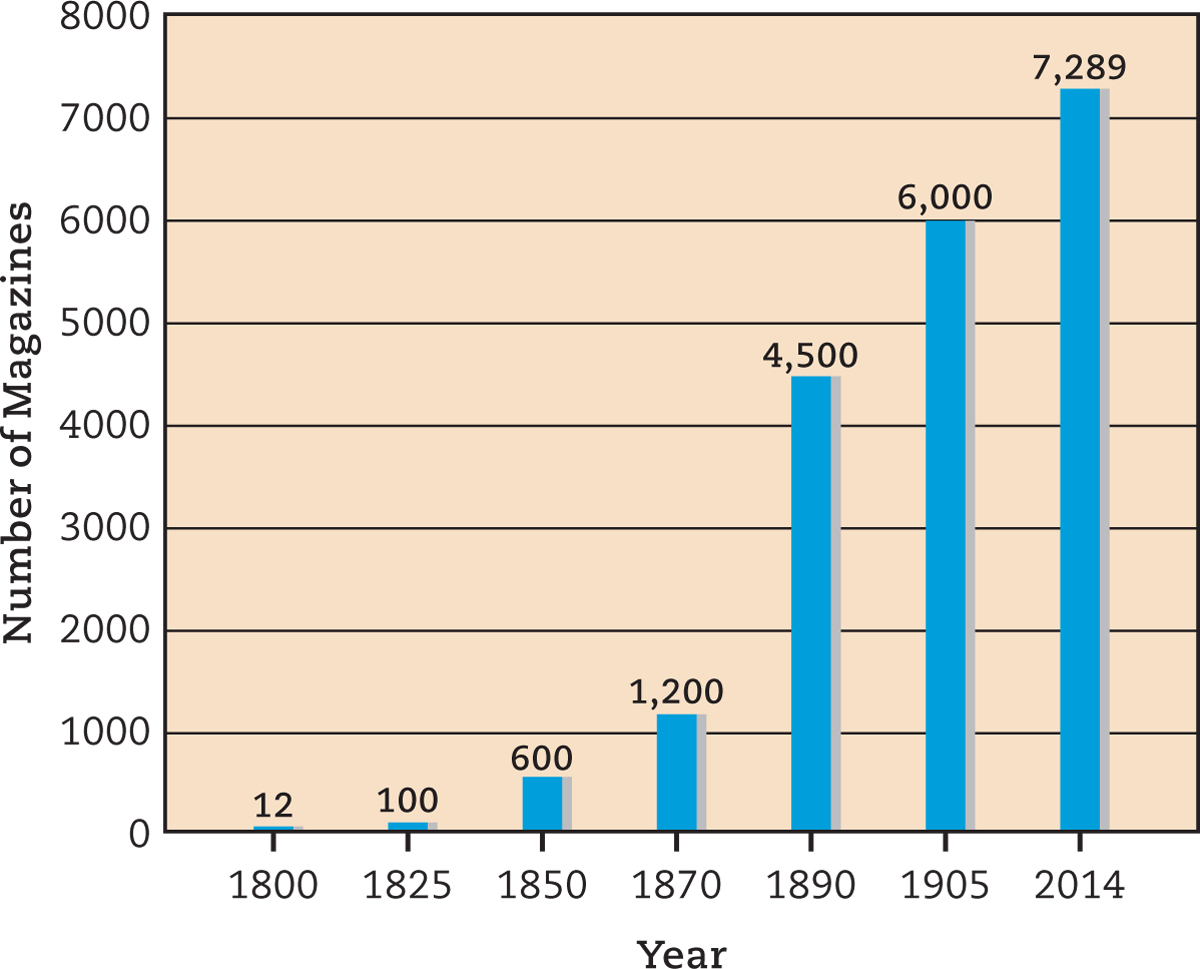

FIGURE 9.1THE GROWTH OF MAGAZINES PUBLISHED IN THE UNITED STATESData from: Association of Magazine Media, 2015 Magazine Media Factbook, www.magazine.org/

In 1870, about twelve hundred magazines were produced in the United States; by 1890, that number had reached forty-

The combination of reduced distribution and production costs enabled publishers to slash magazine prices. As prices dropped from thirty-

As magazine circulation began to skyrocket, advertising revenue soared. The economics behind the rise of advertising was simple: A magazine publisher could dramatically expand circulation by dropping the price of an issue below the actual production cost for a single copy. The publisher recouped the loss through ad revenue, guaranteeing large readerships to advertisers who were willing to pay to reach more readers. The number of ad pages in national magazines proliferated. Harper’s, for instance, devoted only seven pages to ads in the mid-

By the turn of the century, advertisers increasingly used national magazines to capture consumers’ attention and build a national marketplace. One magazine that took advantage of these changes was Ladies’ Home Journal, begun in 1883 by Cyrus Curtis. The women’s magazine began publishing more than the usual homemaking tips, including also popular fiction, sheet music, and—

Social Reform and the Muckrakers

Better distribution and lower costs had attracted readers, but to maintain sales, magazines had to change content as well. Whereas printing the fiction and essays of the best writers of the day was one way to maintain circulation, many magazines also engaged in one aspect of yellow journalism—crusading for social reform on behalf of the public good. In the 1890s, for example, Ladies’ Home Journal (LHJ) and its editor, Edward Bok, led the fight against unregulated patent medicines (which often contained nearly 50 percent alcohol), while other magazines joined the fight against phony medicines, poor living and working conditions, and unsanitary practices in various food industries.

The rise in magazine circulation coincided with rapid social change in America. While hundreds of thousands of Americans moved from the country to the city in search of industrial jobs, millions of new immigrants also poured in. Thus the nation that journalists had long written about had grown increasingly complex by the turn of the century. Many newspaper reporters became dissatisfied with the simplistic and conventional style of newspaper journalism and turned to magazines, where they were able to write at greater length and in greater depth about broader issues. They wrote about such topics as corruption in big business and government, urban problems faced by immigrants, labor conflicts, and race relations.

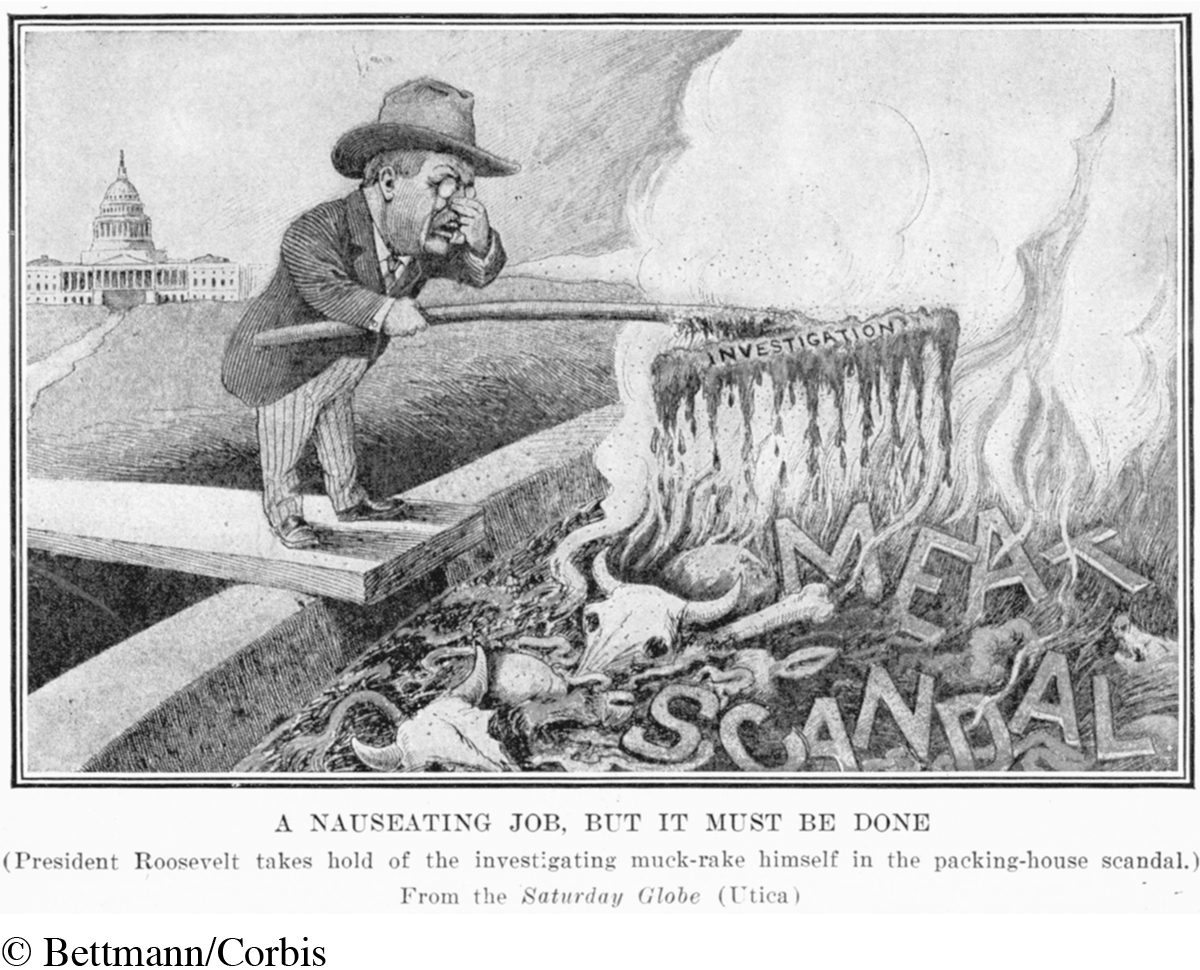

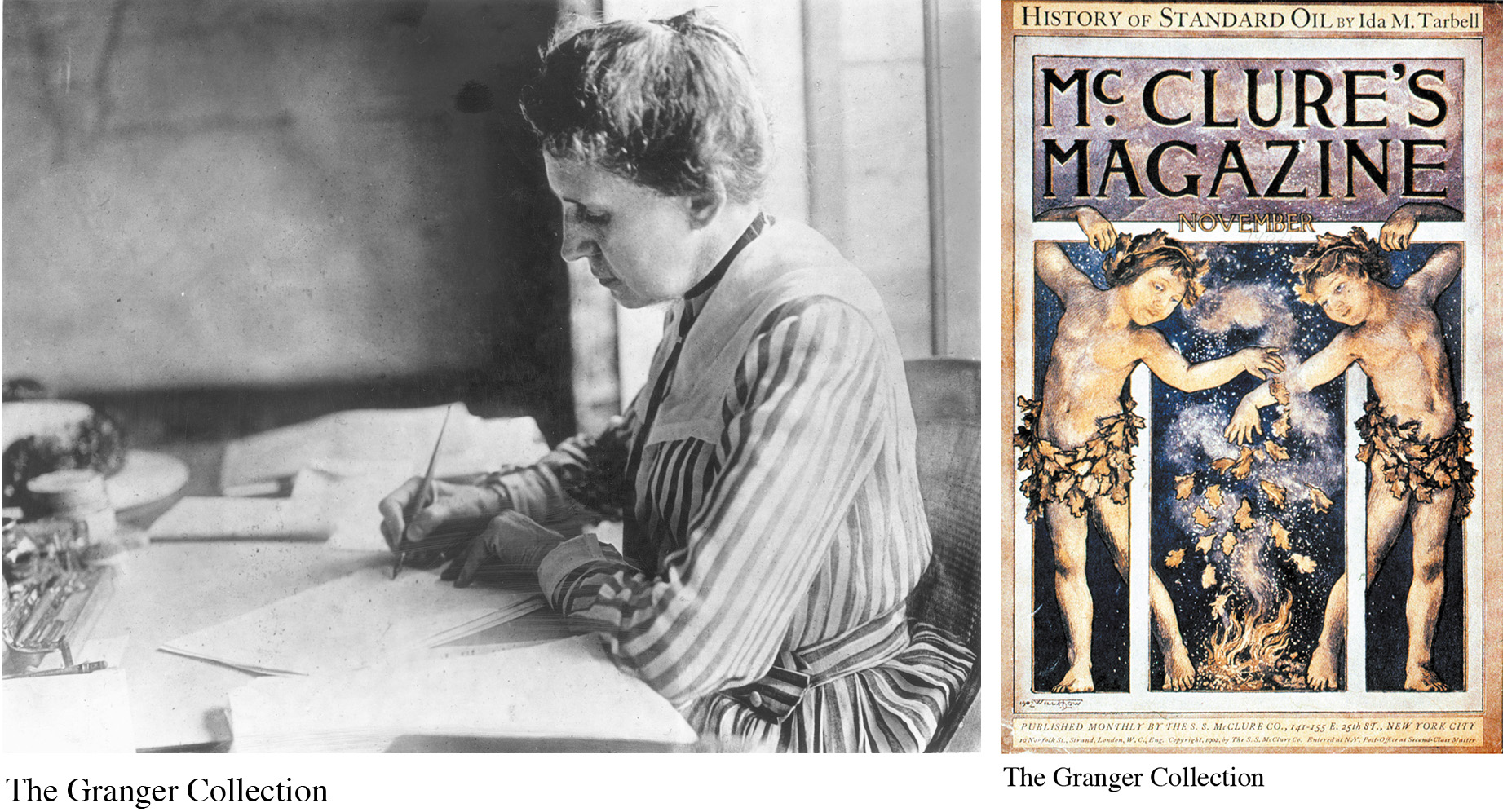

In 1902, McClure’s Magazine (1893–1933) touched off an investigative era in magazine reporting with a series of probing stories, including Ida Tarbell’s “The History of the Standard Oil Company,” which took on John D. Rockefeller’s oil monopoly, and Lincoln Steffens’s “Shame of the Cities,” which tackled urban problems. In 1906, Cosmopolitan joined the fray with a series called “The Treason of the Senate,” and Collier’s magazine (1888–1957) developed “The Great American Fraud” series, focusing on patent medicines (whose ads accounted for 30 percent of the profits made by the American press by the 1890s). Much of this new reporting style was critical of American institutions. Angry with so much negative reporting, in 1906 President Theodore Roosevelt dubbed these investigative reporters muckrakers, because they were willing to crawl through society’s muck to uncover a story. Muckraking was a label that Roosevelt used with disdain, but it was worn with pride by reporters such as Ray Stannard Baker, Frank Norris, and Lincoln Steffens.

Influenced by Upton Sinclair’s novel The Jungle—a fictional account of Chicago’s meatpacking industry—

The Rise of General-

The heyday of the muckraking era lasted into the mid-

IDA TARBELL (1857–1944) is best known for her work “The History of the Standard Oil Company,” which appeared as a nineteen-

Saturday Evening Post

Although it had been around since 1821, the Saturday Evening Post concluded the nineteenth century as only a modest success, with a circulation of about ten thousand. In 1897, Cyrus Curtis, who had already made Ladies’ Home Journal the nation’s top magazine, bought the Post and remade it into the first widely popular general-

Reader’s Digest

The most widely circulated general-

Time

During the general-

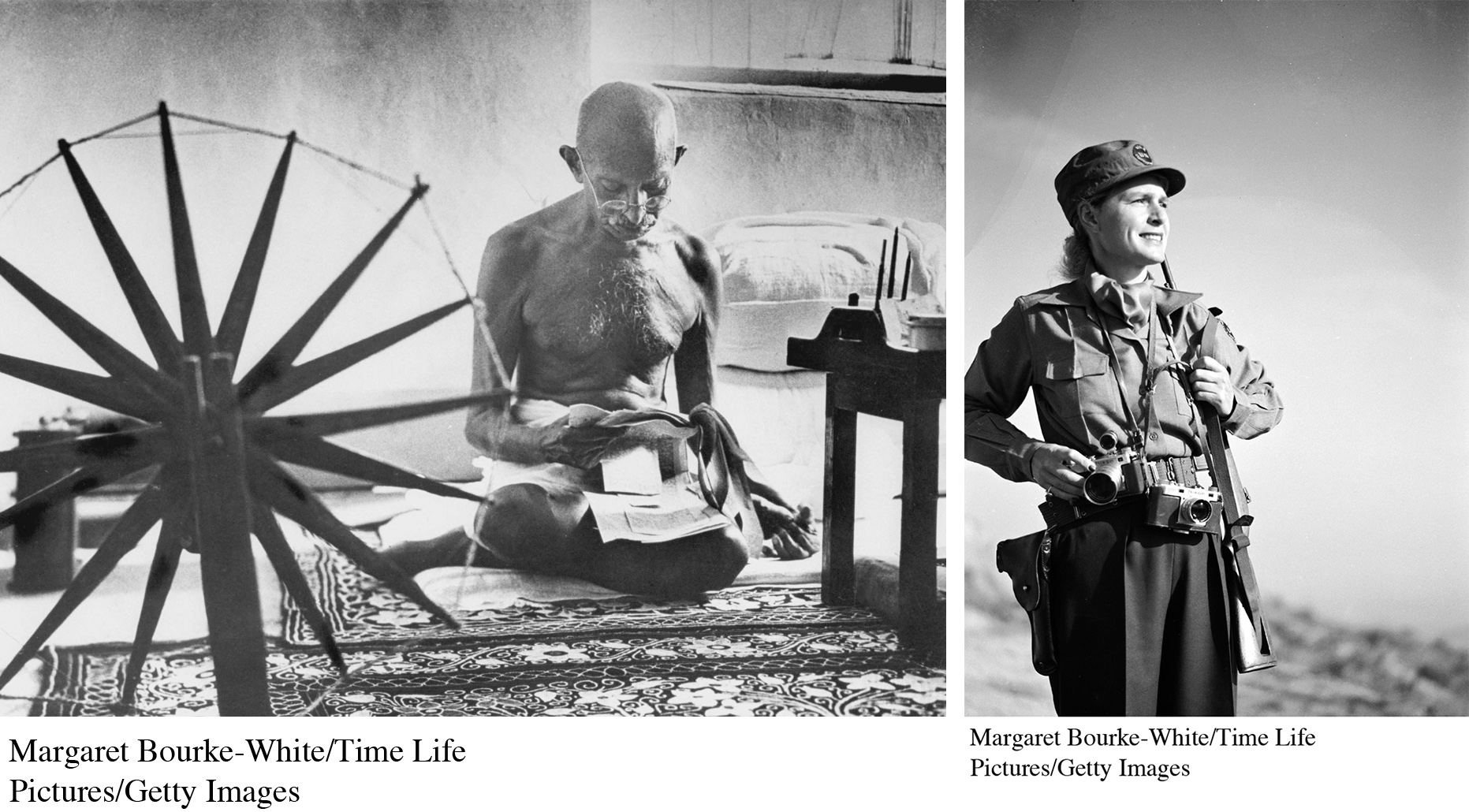

MARGARET BOURKE-

Life

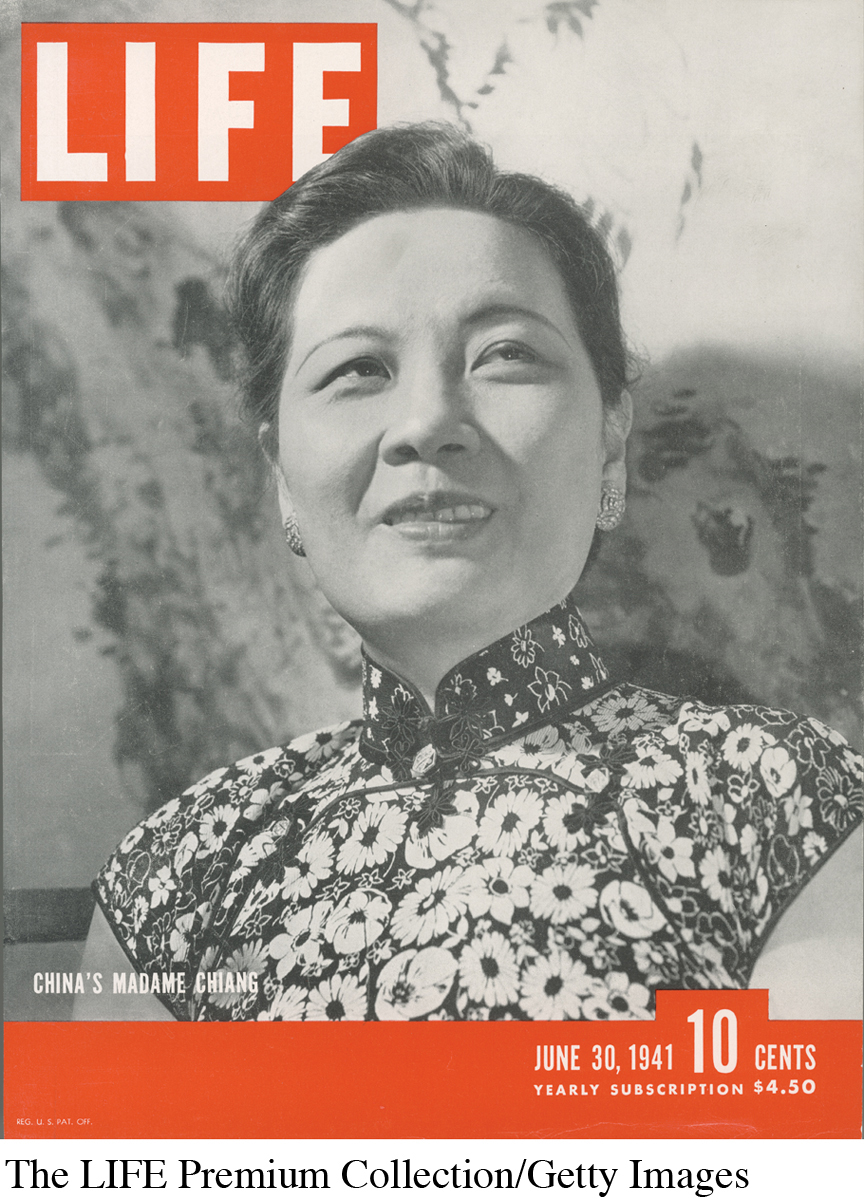

LIFE MAGAZINE published iconic photos during its original 1883–1972 run. Following nearly a century as a weekly, it has since been published as a monthly, an occasional commemorative publication, a newspaper supplement, and an online archive.

Despite the commercial success of Reader’s Digest and Time in the twentieth century, the magazines that really symbolized the general-

Life’s first editor, Wilson Hicks—

The Fall of General-

The decline of weekly general-

CASE STUDY

The Evolution of Photojournalism

by Christopher R. Harris

W hat we now recognize as photojournalism started with the assignment of photographer Roger Fenton, of the Sunday Times of London, to document the Crimean War in 1856. However, technical limitations did not allow direct reproduction of photodocumentary images in the publications of the day. Woodcut artists had to interpret the photographic images as black-

Woodcuts remained the basic method of press reproduction until 1880, when New York Daily Graphic photographer Stephen Horgan invented half-

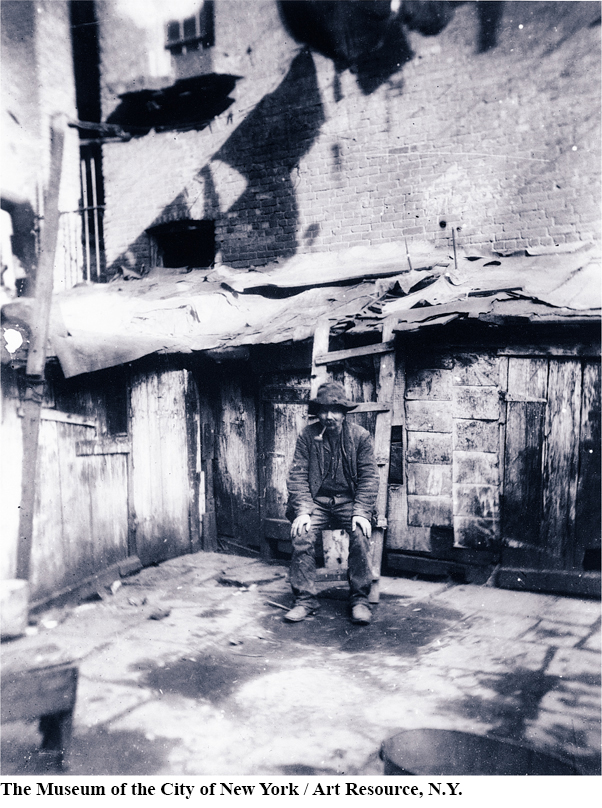

JACOB RIISThe Tramp, c. 1890. Riis, who emigrated from Denmark in 1870, lived in poverty in New York for several years before becoming a photojournalist. He spent much of his later life chronicling the lives of the poor in New York City. The Museum of the City of New York /Art Resource, N.Y.

In the mid-

In 1888, George Eastman brought photography to the working and middle classes when he introduced the first flexible-

As photography became easier and more widespread, photojournalism began to take on an increasingly important social role. At the turn of the century, the documentary photography of Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine captured the harsh living and working conditions of the nation’s many child laborers, including crowded ghettos and unsafe mills and factories. Reaction to these shockingly honest photographs resulted in public outcry and new laws against the exploitation of children. Photographs also brought the horrors of World War I to people far from the battlefields.

In 1923, visionaries Henry Luce and Briton Hadden published Time, the first modern photographic newsweekly; Life and Fortune soon followed. From coverage of the Roaring Twenties to the Great Depression, these magazines used images that changed the way people viewed the world.

Life, with its spacious 10-

Television photojournalism made its quantum leap into the public mind as it documented the assassination of President Kennedy in 1963. In televised images that were broadcast and rebroadcast, the public witnessed the actual assassination and the confusing aftermath, including live coverage of the murder of alleged assassin Lee Harvey Oswald and of President Kennedy’s funeral procession. Photojournalism also provided visual documentation of the turbulent 1960s, including aggressive photographic coverage of the Vietnam War—

In the 1970s, new computer technologies emerged and were embraced by print and television media worldwide. By the late 1980s, computers could transform images into digital form and easily manipulate them with sophisticated software programs. Today, a reporter can take a picture and within minutes send it to news offices in Tokyo, Berlin, and New York; moments later, the image can be used in a late-

However, there is a dark side to all this digital technology. Because of the absence of physical film, there is a loss of proof, or veracity, of the authenticity of images. Original film has qualities that make it easy to determine whether it has been tampered with. Digital images, by contrast, can be easily altered, and such alteration can be very difficult to detect.

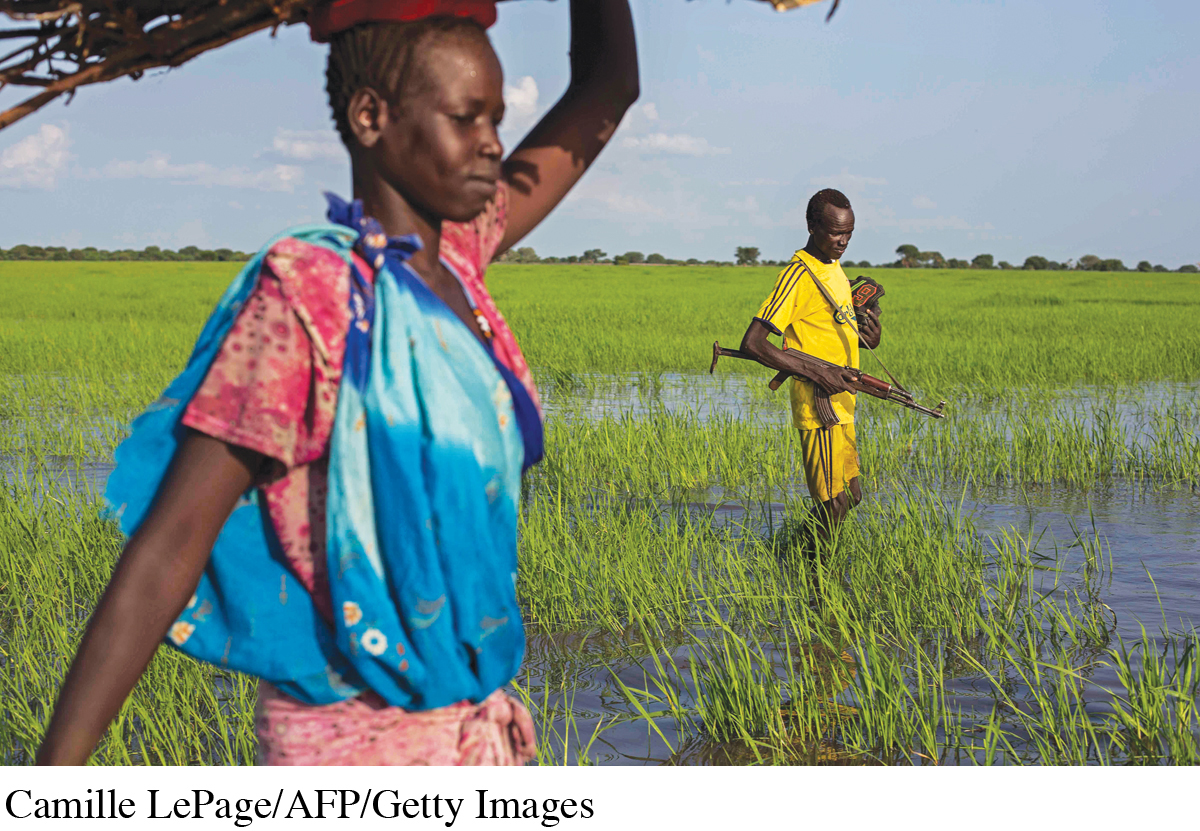

CAMILLE LEPAGE, a twenty-

An egregious example of image-

Photojournalists and news sources are confronted today with unprecedented concerns over truth-

Christopher R. Harris is a professor in the Department of Electronic Media Communication at Middle Tennessee State University.

TV Guide Is Born

While other magazines were just beginning to make sense of the impact of television on their readers, TV Guide appeared in 1953. Taking its cue from the pocket-

| 1972 | 2014 | ||

| Rank/Publication | Circulation | Rank/Publication | Circulation |

| 1 Reader’s Digest | 17,825,661 | 1 AARP The Magazine | 22,837,736 |

| 2 TV Guide | 16,410,858 | 2 AARP Bulletin | 22,183,316 |

| 3 Woman’s Day | 8,191,731 | 3 Better Homes and Gardens | 7,639,661 |

| 4 Better Homes and Gardens | 7,996,050 | 4 Game Informer | 7,099,452 |

| 5 Family Circle | 7,889,587 | 5 Good Housekeeping | 4,315,330 |

| 6 McCall’s | 7,516,960 | 6 Family Circle | 4,015,728 |

| 7 National Geographic | 7,260,179 | 7 National Geographic | 3,572,348 |

| 8 Ladies’ Home Journal | 7,014,251 | 8 People | 3,510,533 |

| 9 Playboy | 6,400,573 | 9 Reader’s Digest | 3,393,573 |

| 10 Good Housekeeping | 5,801,446 | 10 Woman’s Day | 3,288,335 |

Table 9.1: TABLE 9.1 THE TOP 10 MAGAZINES (RANKED BY PAID U.S. CIRCULATION AND SINGLE-

TV Guide’s story illustrates a number of key trends that affected magazines beginning in the 1950s. First, TV Guide highlighted America’s new interest in specialized magazines. Second, it demonstrated the growing sales power of the nation’s checkout lines, which also sustained the high circulation rates of women’s magazines and supermarket tabloids. Third, TV Guide underscored the fact that magazines were facing the same challenge as other mass media in the 1950s: the growing power of television. TV Guide would rank among the nation’s most popular magazines in the twentieth century.

In 1988, media baron Rupert Murdoch acquired Triangle Publications for $3 billion. Murdoch’s News Corp. owned the new Fox network, and buying the then influential TV Guide ensured that the fledgling network would have its programs listed. In 2005, after years of declining circulation (TV schedules in local newspapers had increasingly undermined its regional editions), TV Guide became a full-

Saturday Evening Post, Life, and Look Expire

Although Reader’s Digest and women’s supermarket magazines were not greatly affected by television, other general-

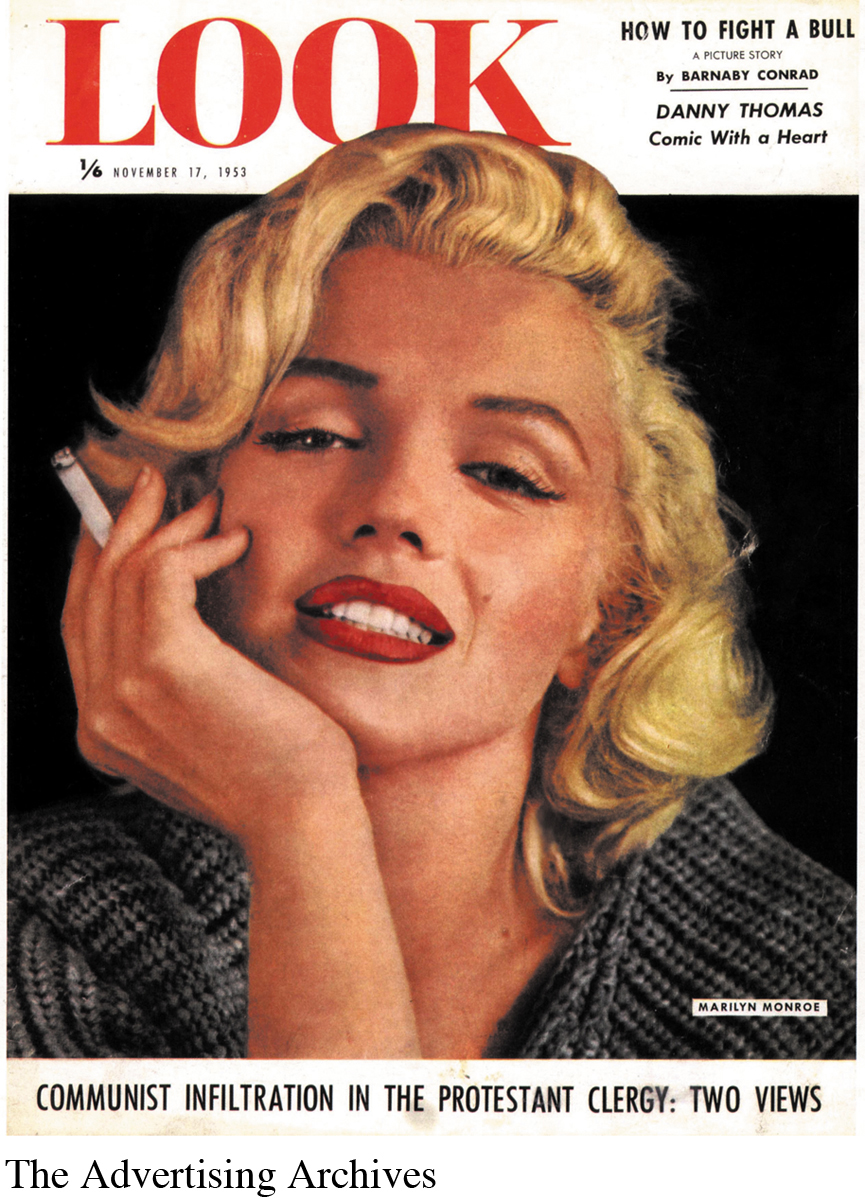

THE RISE AND FALL OF LOOK With large pages, beautiful photographs, and compelling stories on celebrities like Marilyn Monroe, Look entertained millions of readers from 1937 to 1971, emphasizing photojournalism to compete with radio. By the late 1960s, however, TV lured away national advertisers, postal rates increased, and production costs rose, forcing Look to fold despite a readership of more than eight million.

Second, the national advertising revenue pie that helped make up the cost differences for Life and Look now had to be shared with network television—

Third, dramatic increases in postal rates had a particularly negative effect on oversized publications (those larger than the 8-

The general-

People Puts Life Back into Magazines

In March 1974, Time Inc. launched People, the first successful mass market magazine to appear in decades. With an abundance of celebrity profiles and human-

The success of People is instructive, particularly because only two years earlier television had helped kill Life by draining away national ad dollars. Instead of using a bulky oversized format and relying on subscriptions, People downsized and generated most of its circulation revenue from newsstand and supermarket sales. For content, it took its cue from our culture’s fascination with celebrities. Supported by plenty of photos, its short articles are about one-

Although People has not achieved the broad popularity that Life once commanded, it does seem to defy the contemporary trend of specialized magazines aimed at narrow but well-

Convergence: Magazines Confront the Digital Age

REGIONAL MAGAZINES maintain a healthy readership in some areas, with sometimes award-

Although the Internet was initially viewed as the death knell of print magazines, the industry now embraces it. The Internet has become the place where print magazines like Time and Entertainment Weekly can extend their reach, where some magazines like FHM and PCWorld can survive when their print version ends, or where online magazines like Salon, Slate, and Wonderwall can exist exclusively.

Magazines Move Online

Given the costs of paper, printing, and postage, creating magazine companion Web sites is a popular method for expanding the reach of consumer magazines. For example, Wired magazine has a print circulation of about 853,000. Online, Wired.com gets an average of 19 million unique visitors per month. Mobile magazine apps have become even more popular. Between 2010 and 2012, the number of U.S. consumer magazine iPad apps grew from 98 to 2,234.8

The Web and app formats give magazines unlimited space, which is at a premium in their printed versions, and the opportunity to do things that print can’t do. Many online magazines now include blogs, original video and audio podcasts, social networks, games, virtual fitting rooms, and 3-

Paperless: Magazines Embrace Digital Content

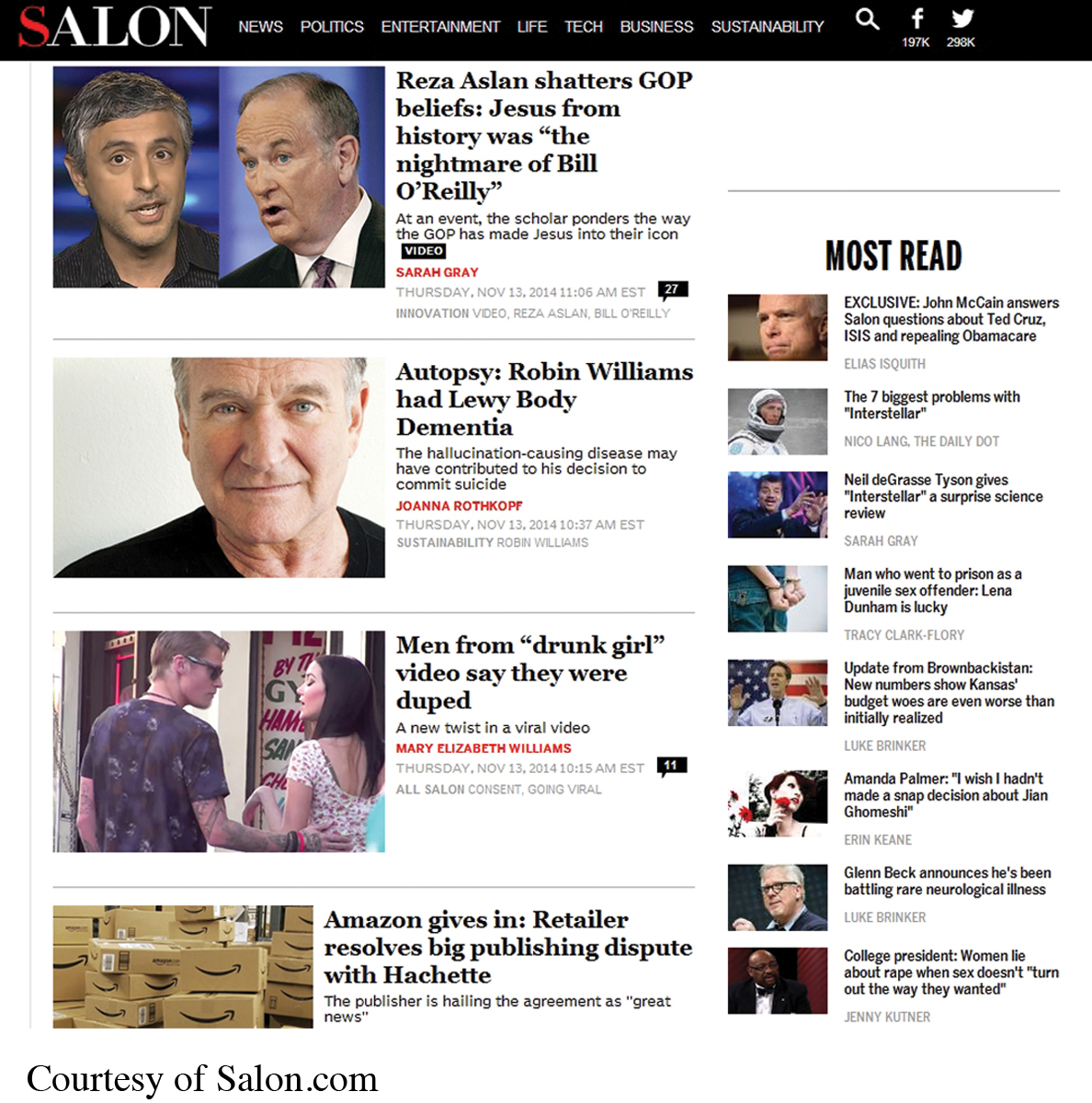

SALON, launched in 1995, is now a leading Internet entertainment magazine. Though it was created by former newspaper staffers, its mixture of topics and article lengths, as well as its national scope, makes it more akin to a general-

Webzines such as Salon and Slate, which are magazines that appear exclusively online, were pioneers in making the Web a legitimate site for breaking news and discussing culture and politics. Salon was founded in 1995 by five former reporters from the San Francisco Examiner who wanted to break from the traditions of newspaper publishing and build “a different kind of newsroom” to create well-

Other online-