9.5 Fossil fuel extraction and use can harm the environment

Can the economic challenges associated with a potential peak in oil production be extended to potential peaks in natural gas and coal?

As we saw with the Deepwater Horizon spill, the extraction and use of fossil fuels can cause serious harm to the environment, but a disaster like that is not the only way that damage occurs. Burning of fossil fuels can produce pollution, such as acid rain, which has significantly impacted both terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems over vast regions (see Chapter 13). Burning of coal releases heavy metals (e.g., mercury and lead) into the air, which settle on landscapes and in waterways, thus threatening human health. Fossil fuel burning also adds carbon dioxide to the atmosphere, which drives climate change (see Chapter 14). But at a more basic level, physically extracting fossil fuels from the earth involves building roads and infrastructure, clearing forests and other ecosystems, and drilling or mining, which can cause environmental damage even under the best conditions.

Coal Mining and the Land

overburden The layer of rock overlying a mineral deposit (e.g., coal).

Coal is extracted from the earth using both underground mining and surface mining. When the layer of rock above the coal, known as overburden, is thicker, underground or subsurface mining is generally used; where it is thinner, coal is usually extracted by surface mining.

What are some direct and indirect impacts of fossil fuel use other than those briefly described here?

strip mining A coal extraction technique in which overburden is removed from a long strip of land, exposing a coal seam; once the coal is removed, material from an adjacent strip is used to fill the excavation.

acid mine drainage A problematic result of strip mining, in which surface flow of groundwater turns acidic as it percolates through mine wastes (tailings).

Where the land is not too steep, the surface mining technique generally used to extract coal is strip mining. In this process, overburden is removed from a long strip of land, exposing a coal seam. Once the coal is removed, material from an adjacent strip is used to fill the excavation. Strip mining can leave a severely scarred landscape in its wake (Figure 9.22). The water draining from the disturbed landscape left by coal mining generally has higher acidity, a phenomenon known as acid mine drainage. Where it occurs, acidification can seriously disrupt aquatic ecosystems (see Chapter 13, page 403).

How should we weigh the jobs provided by mountaintop removal mining against the massive environmental damage caused by this approach to coal mining?

mountaintop removal mining An extremely destructive coal mining practice that involves clear-

In steep terrain, such as in the Appalachian Mountains, one of the most destructive coal mining practices ever devised is being used: mountaintop removal mining. Large deposits of high-

The Appalachian Mountains, which run north–

As of 2010, about 410,000 hectares (1.2 million acres) on 500 mountains in Appalachia had undergone mountaintop removal mining. In the process, hundreds of kilometers of streams have been lost and a globally unique and diverse mountain landscape irreversibly altered.

Coal Sludge and Fly Ash Spills

fly ash By-

Extracting, processing, and burning coal produce a tremendous amount of toxic waste. For instance, crushing coal during processing results in coal sludge, a mixture of mineral particles, coal dust, and water. Companies usually store this mixture at the coal-

Breaches and leaks from these ponds have led to numerous environmental calamities. For example, on December 22, 2008, a breach of a storage pond at the Kingston, Tennessee, coal-

However, even without these spills, coal sludge and fly ash can produce serious environmental impacts. These waste products contain large concentrations of heavy metals that can leach into groundwater, contaminating drinking water supplies and poisoning aquatic organisms. Currently, the EPA lists over 70 coal-

Oil Spills

Oil spills such as the Deepwater Horizon provide some of the most familiar examples of how petroleum extraction threatens the environment. Although such catastrophic oil spills make the headlines, they only represent a small fraction of the 29 million gallons of oil that leak into marine environments in North America. A 2003 report from the National Academy of Sciences estimated that only 8% of that total comes from tanker and pipeline spills, whereas oil exploration and extraction account for just 3%. The majority of the oil spilled—

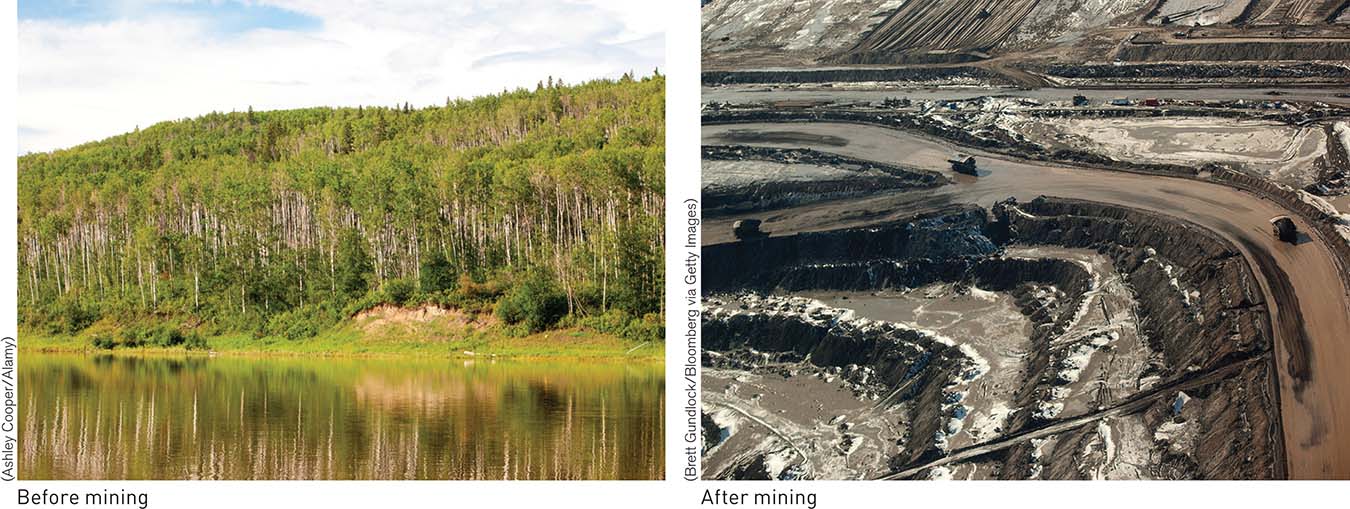

Mining Oil Sands

bitumen A flammable, highly viscous or semisolid mixture of hydrocarbons.

Some of the dirtiest oil on Earth lies deep within the boreal forests of Alberta, Canada. These deposits are known as Athabasca oil sands or tar sands, due to the tarlike consistency of the oils they contain, commonly called bitumen. Bitumen is a flammable, highly viscous or semisolid mixture of hydrocarbons. When these tar sands occur near the land surface, they are mined by removing overburden and transported offsite, where the heavy oils are separated from the sands and clays with which they are mixed. When the oil sands are found farther from the surface, they are heated in place to allow the oil to flow and are then pumped to the surface. In either case, the tar sands oil is more expensive to extract than so-

Various environmentalists, farmers, and landowners in the United States have tried to halt or slow the extraction of tar sands by blocking the approval of the Keystone XL Pipeline, which will transport more than half a million barrels of oil per day from Alberta to the Gulf Coast, where it can be refined and exported. The pipeline will cross the Nebraska Sandhills and the Ogallala Aquifer, which supplies groundwater for drinking and irrigation in eight states from South Dakota to Texas, and many critics fear that an oil spill could be devastating. The TransCanada Corporation, which seeks to build the pipeline, has argued that Keystone will be “the safest pipeline ever built.”

The Fracking Boom

fracking (hydraulic fracturing) An extraction technique that involves drilling horizontally into a rock formation and pumping in a mixture of fluids and sands to fracture it, thus creating a path through which natural gas or oil can flow out.

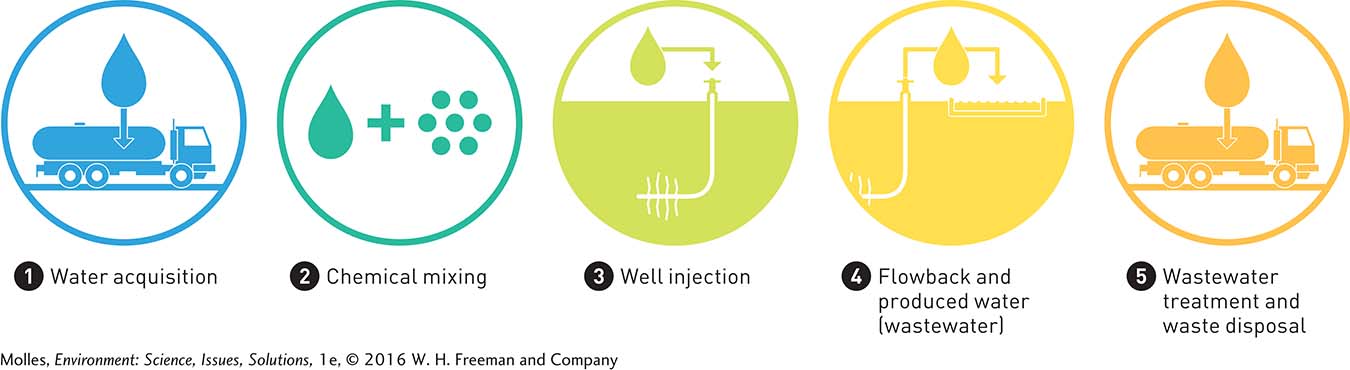

After years of dependence on foreign oil, the United States is experiencing a resurgence of cheap energy through a boom in fracking, which poses new threats to the environment. Fracking (hydraulic fracturing) is a controversial extraction technique used when oil or natural gas is tightly bound in geologic formations, such as the Bakken Shale of North Dakota or the Marcellus Shale of Pennsylvania, and cannot be pumped from the formation using conventional technology. Fracking involves drilling horizontally into a rock formation and pumping in a mixture of fluids and sands to fracture it. The fractures, which are held open by the sand in the fracking fluid, create a path through which natural gas or oil can flow out of the formation. While hydraulic fracturing has been used for more than 50 years, new technology, including horizontal drilling and new chemical mixtures, provide access to previously unavailable natural gas deposits.

The EPA has identified numerous ways that fracking can impact surface or groundwater sources of drinking water, as has occurred in Pennsylvania and West Virginia (EPA, 2015). Fracking operations generally involve pumping millions of gallons of fluid in each well. Thus, the two main concerns are that fracking potentially reduces drinking water supplies, as water is pumped from an aquifer or from a lake or river, and that the chemicals in the fracking fluids could contaminate drinking water (Figure 9.26).

The fracking fluids contain 98% water and sand and 2% chemical additives. What are these additives? Companies have used more than 1,000 different chemical compounds in various fracking operations, the most common ingredients being hydrochloric acid, methanol, and petroleum derivatives. But not all the ingredients are known: Companies have refused to disclose the identity of 10% of them for “proprietary business reasons.” Regardless, the EPA did gather enough information to evaluate human health effects of 73 of the “mystery ingredients” and found that they included carcinogens and other toxic substances affecting heart, liver, kidney, and reproductive systems (see Chapter 11, page 332).

Furthermore, the EPA identified a number of instances in which contamination of drinking water due to fracking has been verified. But that number was relatively small compared with the number of fracking wells that have been drilled in the country. As a result, the study concluded that fracking has not produced “widespread, systemic impacts on drinking water resources in the United States.” In other words, contamination of drinking water by fracking has been a local or regional problem. While the petroleum industry lauded the report as demonstrating that fracking is therefore indeed safe, environmental organizations emphasized that the study confirmed fracking still has the potential to contaminate drinking water.

Another area of concern is an uptick in the number of earthquakes in areas where fracking activity has increased. According to the United States Geological Survey (USGS), the frequency of noticeable earthquakes (magnitude 3 or higher) in the central and eastern United States began increasing sharply around 2009. Oklahoma has been particularly hard hit. One earthquake in November 2011 struck near the town of Prague and caused more than $10 million worth of damage. And during 2014 Oklahoma recorded 15 magnitude-

A recent USGS report, however, concluded that fracking was not responsible for most of these earthquakes. Rather, it laid the blame on another controversial practice of the energy industry: injecting wastewater into deep wells (see Chapter 12, page 381). Drillers in this region have been pumping up a briny mixture containing oil and gas—

Think About It

A company causing environmental damage during the course of fossil fuel extraction or transport is generally required to pay for the damages caused, as well as the cleanup. However, are there ways that the market might positively reward those companies that extract and transport such resources without environmental damage?

While the United States fined BP for the Deepwater Horizon oil spill and the company is paying for economic damages, Brazil filed criminal charges that could result in long prison terms for energy-

company personnel involved in oil spills off its coast in 2011. How do you think environmental impacts should be penalized? Include an analysis of the costs and benefits of potential penalties.