9.8 Ecosystem restoration can mitigate the environmental impacts of fossil fuel extraction

reclamation A process that restores an ecosystem to its natural structure and functioning prior to mining or to an economically usable state.

Strip mining for coal, oil sands mining, and mountain top removal mining of coal all have the potential to destroy vast tracts of natural ecosystems. To reduce these environmental impacts, laws in the United States and other countries require miners of these resources and elsewhere to repair damages done to mined lands. In the United States, the federal law mandating restoration is the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA), which came into force in 1977. The laws of individual state and local authorities also generally require mine reclamation, that is, restoring an ecosystem to its natural structure and functioning prior to mining or to an economically usable state. According to the National Mining Association, more than 900,000 hectares (2.2 million acres) of mined lands have been restored in the United States alone. In many cases, ecosystem restoration has been remarkably successful.

Restoration of Strip-Mined Prairie

The state of Wyoming includes some of the most valuable low-

The mine, which is owned and operated by Rio Tinto Energy America, naturally supports a semi-

Is it possible to “improve” a landscape over its condition prior to disturbance by mining? If so, what criteria would you use?

One restored area at the Jacobs Ranch Mine, identified as critical winter habitat for the local elk herd by the Wyoming Department of Game and Fish, has become a showcase for ecological restoration and cooperative work between industry and conservation organizations. In 2004 Rio Tinto Energy America began working with the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation to create a 405-

Restoration of Boreal Forest Oil Sands Mining

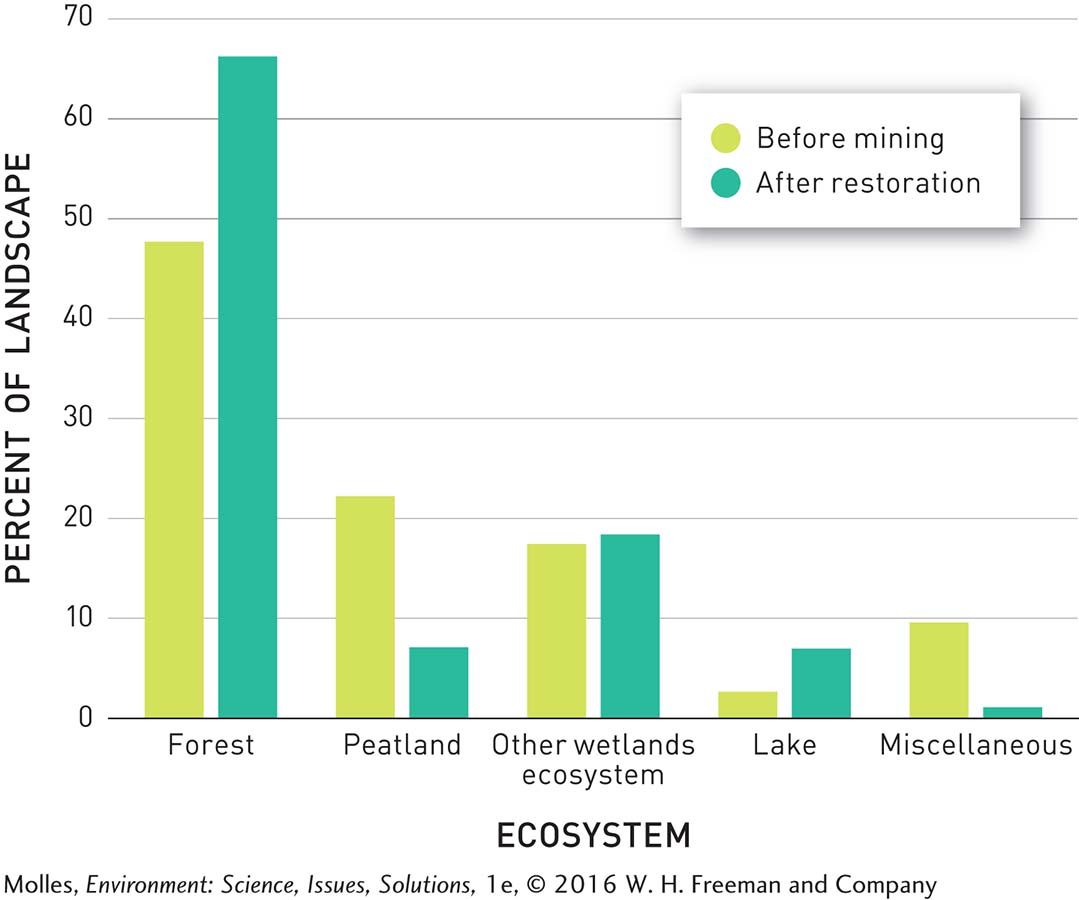

Sometimes it’s not possible to restore a landscape to its natural state. The boreal forest where oil sands extraction takes place is a patchwork of forest, lakes, and several types of wetlands. This patchwork is going to look very different in the future (Figure 9.32). The area of forest will increase by 40% and the area of lakes by 177%, while the total area of wetlands will decrease by 36%. Most significant, the area of peat wetlands will decrease by 67%.

Peat wetlands are the result of centuries of development, and they cannot be restored. The loss of these peat wetlands is environmentally significant because they are a major repository of climate-

Restoration Following Mountaintop Removal Mining

Once you’ve blown off the top of a mountain with explosives and dumped the material into adjacent valleys, how do you replace it? You can’t.

However, it turns out there’s a loophole in the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977. The law requires that land be restored to a natural condition similar to that prior to mining or to an economically useful condition. Companies involved in mountaintop removal mining have taken this second course and have not attempted to restore the natural mountain contours, which, if not impossible, would not be economically feasible. Consequently, areas that were once forested peaks are now large, flat or gently sloping patches in an otherwise mountainous landscape (Figure 9.33). They have become grazing lands, forestry plantations, or wildlife areas.

What are the relative challenges involved in restoring a prairie grassland versus an old growth forest disturbed by fossil fuel extraction?

The state of Kentucky, for instance, working with several mining companies and the Rocky Mountain Elk Federation, has reintroduced elk, which were extirpated from the region long ago. Kentucky’s reintroduced elk mainly use grazing lands on restored mountaintop mining areas, where the population has grown rapidly to over 10,000 individuals and is now the focus of hunting in the region. Other economic developments on reclaimed mountaintop mine lands include golf courses, regional airports, correctional facilities, and industrial parks. Mining companies cite these economic developments as positive benefits to the largely impoverished region.

Critics of mountaintop removal mining assert that there has been too little economic development of the reclaimed mining areas and that what has occurred has been at the expense of one of North America’s biodiversity hotspots. Indeed, the soils, one of the foundations of terrestrial ecosystem productivity and health (see Chapter 7, page 194), in areas reclaimed after mountaintop removal mining are deficient in several ways. They are denser and much lower in organic matter content, which reduces water infiltration and favors surface runoff. Many areas remain barren after 15 years or more. In addition, critics argue that grazing lands inhabited by elk cannot compensate for the valleys and headwater streams, home to exceptionally species-

Think About It

What are the unique challenges and opportunities of restoring Wyoming’s surface-

mined prairies, the boreal forests landscape overlying the Athabasca oil sands, and the Appalachian mountaintops that have been removed? How would you go about evaluating the relative merits of restoration of mined lands to a state of economic usefulness versus their original condition?