Chapter 3 Introduction

CHAPTER 3

Visual Displays of Data

“The Most Misleading Graph Ever Published”

Techniques for Misleading with Graphs

Scatterplots

Line Graphs

Bar Graphs

Pictorial Graphs

Pie Charts

Choosing the Appropriate Type of Graph

How to Read a Graph

Guidelines for Creating a Graph

The Future of Graphs

BEFORE YOU GO ON

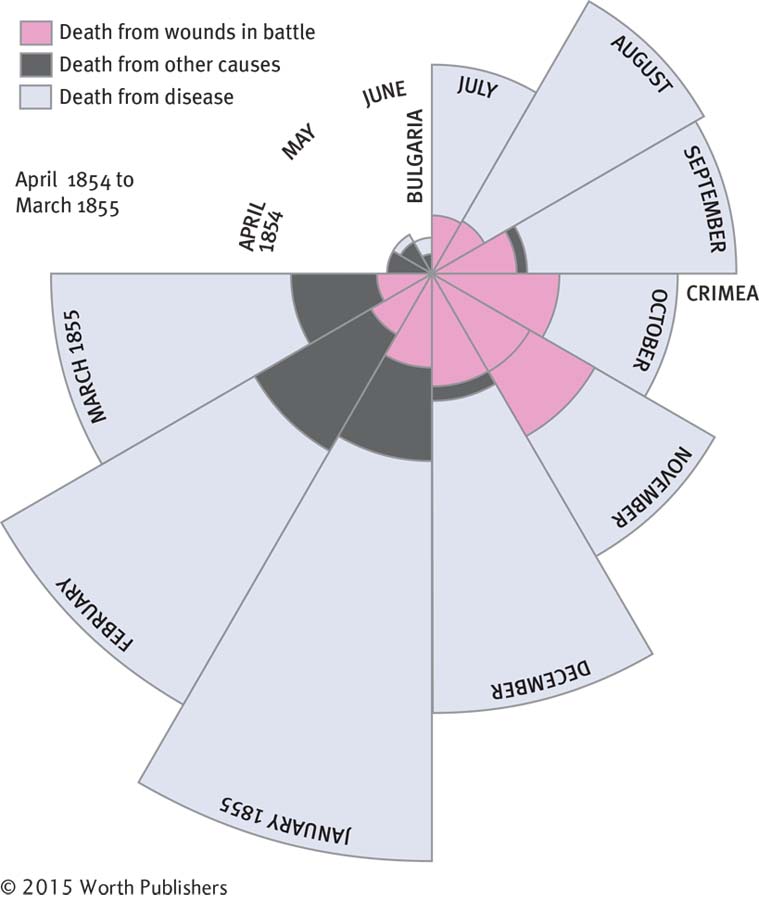

The legendary nineteenth-

Graphs continue to save lives. Recent research documents the power of graphs to guide decisions about health care and even to reduce risky health-

This chapter shows you how to create graphs, called figures in APA-

Graphs That Persuade

This coxcomb graph, based on Florence Nightingale’s original coxcomb graph, “Diagram of the Causes of Mortality in the Army in the East,” addresses the period from April 1854 to March 1855. It is called a coxcomb graph because the data arrangement resembles the shape of a rooster’s head. The 12 sections represent the ordinal variable of a year broken into 12 months. The size of the sections representing each month indicates the scale variable of how many people died in that particular month. The colors represent the nominal variable of cause of death.