Exercises

Clarifying the Concepts

Question 9.1

| 9.1 |

When should we use a t distribution? |

Question 9.2

| 9.2 |

Why do we modify the formula for calculating standard deviation when using t tests (and divide by N − 1)? |

Question 9.3

| 9.3 |

How is the calculation of standard error different for a t test than for a z test? |

Question 9.4

| 9.4 |

Explain why the standard error for the distribution of sample means is smaller than the standard deviation of sample scores. |

Question 9.5

| 9.5 |

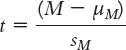

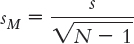

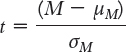

Define the symbols in the formula for the t statistic: |

Question 9.6

| 9.6 |

When is it appropriate to use a single- |

Question 9.7

| 9.7 |

What does the phrase “free to vary,” referring to a number of scores in a given sample, mean for statisticians? |

Question 9.8

| 9.8 |

How are the critical t values affected by sample size and degrees of freedom? |

Question 9.9

| 9.9 |

Why do the t distributions merge with the z distribution as sample size increases? |

Question 9.10

| 9.10 |

Explain what each part of the following statistical phrase means, as it would be reported in APA format: t(4) = 2.87, p = 0.032. |

Question 9.11

| 9.11 |

What do we mean when we say we have a distribution of mean differences? |

Question 9.12

| 9.12 |

When do we use a paired- |

Question 9.13

| 9.13 |

Explain the distinction between the terms independent samples and paired samples as they relate to t tests. |

Question 9.14

| 9.14 |

How is a paired- |

Question 9.15

| 9.15 |

How is a paired- |

Question 9.16

| 9.16 |

Why is the population mean almost always equal to 0 for the null hypothesis in the two- |

Question 9.17

| 9.17 |

If we calculate the confidence interval around the sample mean difference used for a paired- |

Question 9.18

| 9.18 |

If we calculate the confidence interval around the sample mean difference used for a paired- |

Question 9.19

| 9.19 |

Why is a confidence interval more useful than a single- |

Question 9.20

| 9.20 |

What is the appropriate effect size for a paired- |

Question 9.21

| 9.21 |

For a paired- |

Calculating the Statistics

Question 9.22

| 9.22 |

We use formulas to describe calculations. Find the error in each of the following formulas. Explain why each is incorrect and provide a correction. |

Question 9.23

| 9.23 |

For the data 93, 97, 91, 88, 103, 94, 97, calculate the standard deviation under both of these conditions:

|

Question 9.24

| 9.24 |

For the data 1.01, 0.99, 1.12, 1.27, 0.82, 1.04, calculate the standard deviation under both of the following conditions. (Note: You will have to carry some calculations out to the third decimal place to see the difference in calculations.)

|

Question 9.25

| 9.25 |

Identify the critical t value in each of the following circumstances:

|

Question 9.26

| 9.26 |

Calculate degrees of freedom and identify the critical t value for a single-

|

Question 9.27

| 9.27 |

Identify the critical t values for each of the following tests:

|

Question 9.28

| 9.28 |

Assume we know the following for a two-

|

Question 9.29

| 9.29 |

Assume we know the following for a two-

|

Question 9.30

| 9.30 |

Using Cohen’s conventions, interpret the effect sizes that you calculated in:

|

Question 9.31

| 9.31 |

Identify critical t values for each of the following tests:

|

Question 9.32

| 9.32 |

Assume 8 participants completed a mood scale before and after watching a funny video clip.

|

Question 9.33

| 9.33 |

The following are scores for 8 students on two different exams.

|

Question 9.34

| 9.34 |

The following are mood scores for 12 participants before and after watching a funny video clip (higher values indicate better mood).

|

Question 9.35

| 9.35 |

Consider the following data:

|

Question 9.36

| 9.36 |

Consider the following data.

|

Question 9.37

| 9.37 |

Assume we know the following for a paired-

|

Question 9.38

| 9.38 |

Assume we know the following for a paired-

|

Applying the Concepts

Question 9.39

| 9.39 |

The relation between the z distribution and the t distributions: For the hypothesis tests described below in parts (a) through (c), one of which is the same as that described in Exercise 9.31a, identify what the critical z value would have been if there had been just one sample and we knew the mean and standard deviation of the population:

|

Question 9.40

| 9.40 |

t statistics and standardized tests: On its Web site, the Princeton Review claims that students who have taken its course improve their Graduate Record Examination (GRE) scores, on average, by 210 points (based on the old scoring system). (No other information is provided about this statistic.) Treating this average gain as a population mean, a researcher wonders whether the far cheaper technique of practicing for the GRE on one’s own would lead to a different average gain. She randomly selects five students from the pool of students at her university who plan to take the GRE. The students take a practice test before and after 2 months of self-

|

Question 9.41

| 9.41 |

Single-

|

Question 9.42

| 9.42 |

t tests and the cost of Levi’s jeans and H&M dresses in Halifax: Numbeo is a crowd- Page 242

|

Question 9.43

| 9.43 |

Brain exercises and a paired- |

Question 9.44

| 9.44 |

t tests and retail: Many communities worldwide are lamenting the effects of so-

|

Question 9.45

| 9.45 |

Paired-

|

Question 9.46

| 9.46 |

Paired-

|

Question 9.47

| 9.47 |

Attitudes toward statistics and the paired- Page 243

|

Question 9.48

| 9.48 |

Paired-

|

Question 9.49

| 9.49 |

Paired-

|

Putting It All Together

Question 9.50

| 9.50 |

Paid days off and the single-

|

Question 9.51

| 9.51 |

Death row and the single-

|

Question 9.52

| 9.52 |

Political bias in academia and a paired- The American professoriate contains a disproportionate number of people with liberal political views. Is this because of political bias or discrimination?…We sent two emails to directors of graduate study in the leading American departments of sociology, political science, economics, history, and English. The emails came from fictitious students who expressed interest in doing graduate work in the department…. We analyze responses received in terms of frequency, timing, amount of information provided about the department, emotional warmth, and enthusiasm toward the student. (p. 1) One of the fictional emails was from a fictional student who mentioned working on the presidential campaign of John McCain, a well-

|

Question 9.53

| 9.53 |

Hypnosis and the Stroop effect: In Chapter 1, you were given an opportunity to complete the Stroop test, in which color words are printed in the wrong color; for example, the word red might be printed in the color blue. The conflict that arises when we try to name the color of ink the words are printed in but are distracted when the color word does not match the ink color increases reaction time and decreases accuracy. Several researchers have suggested that the Stroop effect can be decreased by hypnosis. Raz, Fan, and Posner (2005) used brain- Page 245

|