13.1 What Is a Psychological Disorder?

Most of us would agree that a family member who is depressed and stays mostly in bed for three months has a psychological disorder. But what should we say about a grieving father who can’t resume his usual social activities three months after his child has died? Where do we draw the line between clinical depression and understandable grief? Between bizarre irrationality and zany creativity? Between abnormality and normality?

In their search for answers, theorists and clinicians ask:

How should we define psychological disorders?

How should we understand disorders? How do underlying biological factors contribute to disorder? How do troubling environments influence our well-

being? And how do these effects of nature and nurture interact? How should we classify psychological disorders? How can we use labels to guide treatment without negatively judging people or excusing their behavior?

Defining Psychological Disorders

LOQ LearningObjectiveQuestion

13-

psychological disorder a syndrome marked by a clinically significant disturbance in a person’s cognition, emotion regulation, or behavior.

A psychological disorder is a syndrome (a collection of symptoms) marked by a “clinically significant disturbance in an individual’s cognitions, emotion regulation, or behavior” (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Such thoughts, emotions, or behaviors are dysfunctional or maladaptive—

Distress often accompanies dysfunctional thoughts, emotions, or behaviors. Marc, Greta, and Stuart were all distressed by their behaviors or emotions.

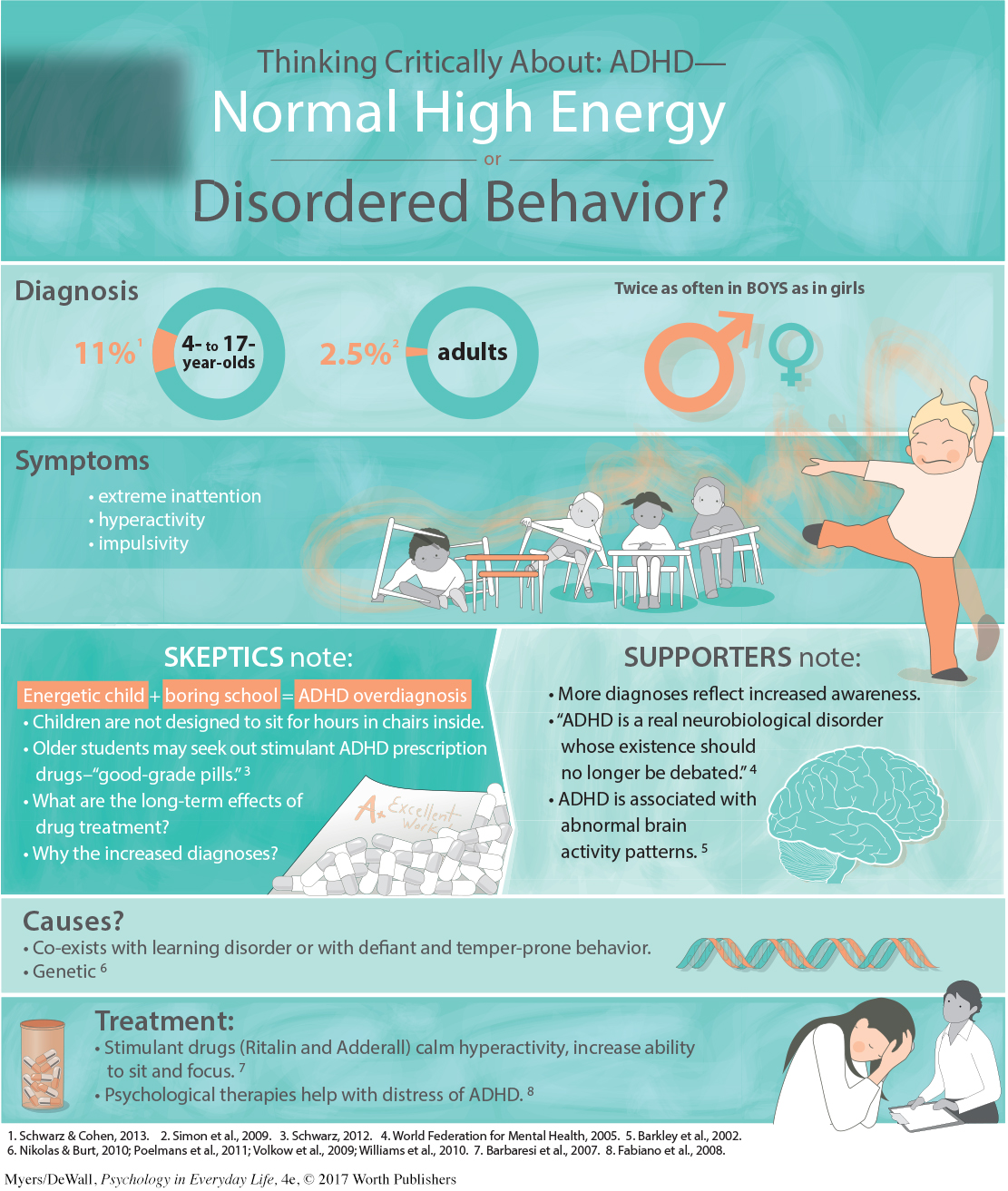

attention-

The diagnosis of specific disorders has varied from culture to culture and even over time in the same culture. The American Psychiatric Association classified homosexuality as a disorder until 1973. By that point, most mental health workers no longer considered same-

LOQ 13-

Retrieve + Remember

Question 13.1

•A lawyer is distressed by feeling the need to wash his hands 100 times a day. He has little time left to meet with clients, and his partners are wondering whether he is a risk to the firm. His behavior would probably be labeled disordered, because it is ______ —that is, it interferes with his day-

ANSWER: dysfunctional or maladaptive

Understanding Psychological Disorders

LOQ 13-

The way we view a problem influences how we try to solve it. In earlier times, people often thought that strange behaviors were evidence of strange forces at work. Had you lived during the Middle Ages, you might have said, “The devil made him do it.” To drive out demons, “mad” people were sometimes caged or given “therapies” such as beatings, genital mutilations, removal of teeth or lengths of intestine, or transfusions of animal blood (Farina, 1982).

Reformers such as Philippe Pinel (1745–

In some places, cruel treatments for mental illness—

The Medical Model

medical model the concept that diseases, in this case psychological disorders, have physical causes that can be diagnosed, treated, and, in most cases, cured, often through treatment in a hospital.

In the 1800s, a medical breakthrough prompted a new perspective on mental disorders. Researchers discovered that syphilis, a sexually transmitted infection, invades the brain and distorts the mind. This discovery triggered an excited search for physical causes of other mental disorders, and for treatments that would cure them. Hospitals replaced madhouses, and the medical model of mental disorders was born. This model is reflected in words we still use today. We speak of the mental health movement. A mental illness needs to be diagnosed on the basis of its symptoms. It needs to be cured through therapy, which may include treatment in a psychiatric hospital. Recent discoveries that abnormal brain structures and biochemistry contribute to some disorders have energized the medical perspective. A growing number of clinical psychologists now work in medical hospitals, where they collaborate with physicians to determine how the mind and body operate together.

The Biopsychosocial Approach

To call psychological disorders “sicknesses” tilts research heavily toward the influence of biology and away from the influence of our personal histories and social and cultural surroundings. But as we have seen throughout this text, our behaviors, our thoughts, and our feelings are formed by the interaction of our biology, our psychology, and our social-

The environment’s influence can be seen in syndromes that are specific to certain cultures (Beardsley, 1994; Castillo, 1997). In Malaysia, for example, a sudden outburst of violent behavior is called amok, as in the English phrase “run amok.” Traditionally, this aggression was believed to be the work of an evil spirit. Anxiety may also wear different faces in different cultures. In Latin American cultures, people may suffer from susto, a condition marked by severe anxiety, restlessness, and a fear of black magic. In Japanese culture, people may experience taijin-

Two other disorders—

epigenetics the study of environmental influences on gene expression that occur without a DNA change.

The biopsychosocial approach reminds us that mind and body work as one. Negative emotions contribute to physical illness, and abnormal physical processes contribute to negative emotions. As research on epigenetics shows, our DNA and our environment interact. In one environment, a gene will be expressed, but in another, it may lie dormant. For some, that will be the difference between developing a disorder or not developing it.

Retrieve + Remember

Question 13.2

•Are psychological disorders universal or culture-

ANSWER: Some psychological disorders are culture-

Question 13.3

•What is the biopsychosocial approach, and why is it important in our understanding of psychological disorders?

ANSWER: Biological, psychological, and social-

Classifying Disorders—and Labeling People

LOQ 13-

In biology, classification creates order and helps us communicate. To say that an animal is a “mammal” tells us a great deal—

But diagnostic classification does more than give us a thumbnail sketch of a person’s disordered behavior, thoughts, or feelings. In psychiatry and psychology, classification also attempts to predict the disorder’s future course and to suggest treatment. And it prompts research into causes. To study a disorder we must first name and describe it.

DSM-

The most common tool for describing disorders and estimating how often they occur is the American Psychiatric Association’s 2013 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, now in its fifth edition (DSM-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

In the new DSM-

In real-

Critics have long faulted the DSM manual for casting too wide a net and bringing “almost any kind of behavior within the compass of psychiatry” (Eysenck et al., 1983). Some now worry that the DSM-

Other critics register a more basic complaint. At best, they say, these labels represent subjective, personal opinions. At worst, these labels represent personal opinions disguised as scientific judgments. Once we label a person, we view that person differently (Bathje & Pryor, 2011; Farina, 1982; Sadler et al., 2012b). Labels can change reality by putting us on alert for evidence that confirms our view. If we hear that a new co-

The biasing power of labels was clear in a now-

Should we be surprised? Surely not. As one psychiatrist noted, if someone swallows blood, goes to an emergency room, and spits it up, we wouldn’t blame the doctor for diagnosing a bleeding ulcer. But what followed the diagnosis in the Rosenhan study was startling. Until being released an average of 19 days later, these eight “patients” showed no other symptoms. Yet after analyzing their (quite normal) life histories, clinicians were able to “discover” the causes of their disorders, such as having mixed emotions about a parent. Even routine note-

Labels matter. When people in another experiment watched videotaped interviews, those told that they were watching job applicants perceived the people as normal (Langer & Abelson, 1974; Langer & Imber, 1980). Others, who were told they were watching cancer or psychiatric patients, perceived them as “different from most people.” One therapist described the person being interviewed as “frightened of his own aggressive impulses,” a “passive, dependent type,” and so forth. As Rosenhan discovered, a label can have “a life and an influence of its own.”

The power of labels is just as real outside the laboratory. Getting a job or finding a place to rent can be a challenge for people recently released from a mental hospital. Label someone as “mentally ill” and people may fear them as potentially violent. That reaction may fade as people better understand that many psychological disorders involve diseases of the brain, not failures of character (Solomon, 1996). Public figures have helped foster this understanding by speaking openly about their own struggles with disorders such as depression and substance abuse.

Despite their risks, diagnostic labels have benefits. They help mental health professionals to communicate about their cases and to study the causes and treatments of disorders. Clients are often relieved to learn that their suffering has a name and that they are not alone in experiencing their symptoms.

In the rest of this chapter, we will discuss some of the major disorders classified in the DSM-

Retrieve + Remember

Question 13.4

•What is the value, and what are the dangers, of labeling individuals with disorders?

ANSWER: Therapists and others apply disorder labels to communicate with one another in a common language. Clients may benefit from knowing they are not the only ones with these symptoms. One danger of labeling is that labels can trigger assumptions that will change people’s behavior toward those labeled.

To test your ability to form diagnoses, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Classifying Disorders.

To test your ability to form diagnoses, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Classifying Disorders.