13.2 Anxiety Disorders, OCD, and PTSD

Anxiety is part of life. Have you ever felt anxious when speaking in front of a class, peering down from a high ledge, or waiting to play in a big game? We all feel anxious at times. We may occasionally feel enough anxiety to avoid making eye contact or talking with someone—

Anxiety Disorders

LOQ 13-

anxiety disorders psychological disorders characterized by distressing, persistent anxiety or maladaptive behaviors that reduce anxiety.

The anxiety disorders are marked by distressing, persistent anxiety or by maladaptive behaviors that reduce anxiety. For example, people with social anxiety disorder become extremely anxious in social settings where others might judge them, such as parties, class presentations, or even eating in a public place. To stave off anxious thoughts and feelings (including physical symptoms such as sweating and trembling), they may avoid going out at all. Even though this behavior reduces their anxiety, it is maladaptive—

In this section we focus on three other anxiety disorders:

Generalized anxiety disorder, in which a person is continually tense and uneasy for no apparent reason.

Panic disorder, in which a person experiences panic attacks—

sudden episodes of intense dread— and often lives in fear of when the next attack might strike. Phobias, in which a person feels irrationally and intensely afraid of a specific object, activity, or situation.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

For two years, Tom, a 27-

generalized anxiety disorder an anxiety disorder in which a person is continually tense, fearful, and in a state of autonomic nervous system arousal.

Tom’s unfocused, out-

The person may not be able to identify the tension’s cause, and therefore cannot relieve or avoid it. To use Sigmund Freud’s term, the anxiety is free-

Panic Disorder

At some point in our life, many of us will experience a terrifying panic attack—

hot and as though I couldn’t breathe. My heart was racing and I started to sweat and tremble and I was sure I was going to faint. Then my fingers started to feel numb and tingly and things seemed unreal. It was so bad I wondered if I was dying and asked my husband to take me to the emergency room. By the time we got there (about 10 minutes) the worst of the attack was over and I just felt washed out (Greist et al., 1986).

panic disorder an anxiety disorder marked by unpredictable minutes-

For the 1 person in 75 with panic disorder, panic attacks are recurrent. These anxiety tornados strike suddenly, do their damage, and disappear, but they are not forgotten. After experiencing even a few panic attacks, people may come to fear the fear itself. Those having (or observing) a panic attack often misread the symptoms as an impending heart attack or other serious physical ailment. Smokers have at least a doubled risk of a panic attack and greater symptoms when they do have an attack (Knuts et al., 2010; Zvolensky & Bernstein, 2005). Because nicotine is a stimulant, lighting up doesn’t lighten up.

The constant fear of another attack can lead people with panic disorder to avoid situations where panic might strike. Their avoidance itself may lead to a separate and additional diagnosis of agoraphobia, the fear of again experiencing the dreaded tornado of anxiety. Fear of being unable to escape or get help during an attack may cause people with agoraphobia to avoid being outside the home, in a crowd, or at a coffee shop. Not all people with panic disorder develop agoraphobia.

Phobias

phobia an anxiety disorder marked by a persistent, irrational fear and avoidance of a specific object, activity, or situation.

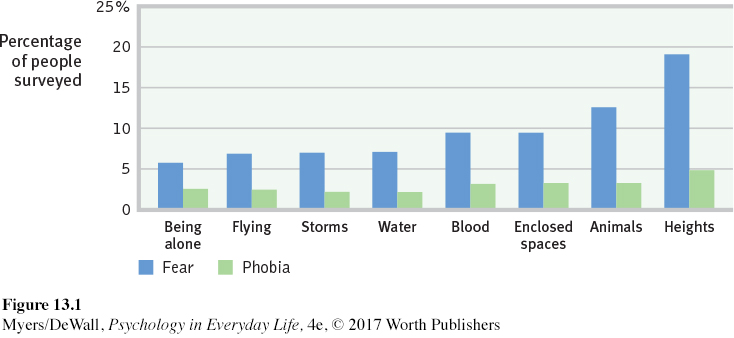

We all live with some fears. People with phobias are consumed by a persistent, irrational fear and avoidance of some object or situation. Specific phobias may focus on particular animals, insects, heights, blood, or enclosed spaces (FIGURE 13.1). Many people avoid the triggers (such as high places) that arouse their fear. Marilyn, an otherwise healthy and happy 28-

Retrieve + Remember

Question 13.5

•Unfocused tension, apprehension, and arousal are symptoms of _________ _______ disorder.

ANSWER: generalized anxiety

Question 13.6

•Those who experience unpredictable periods of terror and intense dread, accompanied by frightening physical sensations, may be diagnosed with a ________ disorder.

ANSWER: panic

Question 13.7

•If a person is focusing anxiety on specific feared objects, activities, or situations, that person may have a ______.

ANSWER: phobia

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

LOQ 13-

obsessive-

As with the anxiety disorders, we can see aspects of our own behavior in obsessive-

On a small scale, obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviors are part of everyday life. Have you ever felt a bit anxious about how your place will appear to others and found yourself checking and cleaning one last time before your guests arrived? Or, perhaps worried about completing an assignment, you caught yourself lining up books or devices “just so” before you began studying? Our lives are full of little rehearsals and fussy behaviors. They cross the fine line between normality and disorder when they persistently interfere with everyday life and cause us distress. Checking to see if you locked your door is normal; checking 10 times is not. Washing your hands is normal; washing so often that your skin becomes raw is not. Although people know their anxiety-

For a 7-

For a 7-

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

LOQ 13-

While serving his country in war, one soldier, Jesse, saw the killing “of children and women. It was just horrible for anyone to experience.” Back home, he suffered “real bad flashbacks” (Welch, 2005).

posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) a disorder characterized by haunting memories, nightmares, social withdrawal, jumpy anxiety, numbness of feeling, and/or insomnia lingering for four weeks or more after a traumatic experience.

Jesse is not alone. In one study of 103,788 veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan, 25 percent were diagnosed with a psychological disorder (Seal et al., 2007). Some had traumatic brain injuries (TBI), but the most frequent diagnosis was posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Survivors of accidents, disasters, and violent and sexual assaults (including an estimated two-

About half of us will experience at least one traumatic event in our lifetime. And most of us will display survivor resiliency—

Among American military personnel in Afghanistan, 7.6 percent of combatants developed PTSD, compared with 1.4 percent of noncombatants (McNally, 2012).

Among survivors of the 9/11 terrorist attacks on New York’s World Trade Center, the rates of subsequent PTSD diagnoses for those who had been inside were double the rates of those who had been outside (Bonanno et al., 2006).

What else can influence PTSD development after a trauma? Some people may have a more sensitive emotion-

Some psychologists believe PTSD has been overdiagnosed (Dobbs, 2009; McNally, 2003). Too often, say critics, PTSD gets stretched to include normal stress-

Retrieve + Remember

Question 13.8

•Those who express anxiety through unwanted repetitive thoughts or actions may have a(n) _____-_______ disorder.

ANSWER: obsessive-

Question 13.9

•Those with symptoms of recurring memories and nightmares, social withdrawal, jumpy anxiety, numbness of feeling, and/or insomnia for weeks after a traumatic event may be diagnosed with ______ ______disorder.

ANSWER: posttraumatic stress

Understanding Anxiety Disorders, OCD, and PTSD

LOQ 13-

Anxiety is both a feeling and a thought—

Conditioning

Conditioning happens when we learn to associate two or more things that occur together. Through classical conditioning, our fear responses can become linked with formerly neutral objects and events. You may recall from Chapter 6 that an infant—

Such research helps explain how anxious or traumatized people come to associate their anxiety with certain cues (Bar-

Stimulus generalization occurs when a person experiences a fearful event and later develops a fear of similar events. My [DM’s] car was once struck by a driver who missed a stop sign. For months afterward, I felt a twinge of unease when any car approached from a side street. Likewise, I [ND] was watching a terrifying movie about spiders, Arachnophobia, when a severe thunderstorm struck and the theater lost power. For months, I experienced anxiety at the sight of spiders or cobwebs. Those fears eventually disappeared, but sometimes fears linger and grow. Marilyn’s thunderstorm phobia may have similarly generalized after a terrifying or painful experience during a thunderstorm.

Reinforcement helps maintain learned fears and anxieties. Anything that enables us to avoid or escape a feared situation reduces our anxiety. This feeling of relief can reinforce maladaptive behaviors. Fearing a panic attack, a person may decide not to leave the house. Reinforced by feeling calmer, the person is likely to repeat that behavior in the future (Antony et al., 1992). Compulsive behaviors operate similarly. If washing your hands relieves your feelings of anxiety, you may wash your hands again when those feelings return.

Cognition

Learning is more than just conditioning. Cognition—

Our interpretations and expectations also shape our reactions. Whether we panic in response to a creaky sound in an old house depends on whether we interpret the sound as the wind or as a possible knife-

Biology

Learning can’t explain all aspects of anxiety disorders, OCD, and PTSD. Why do some of us develop lasting phobias or PTSD after suffering traumas, but others do not? Why do we all learn some fears more readily than others? The answers lie in part in our biology.

GENES Genes matter. Among monkeys, fearfulness runs in families. A monkey reacts more strongly to stress if its close biological relatives have sensitive, high-

So, too, with people. Some of us have genes that make us like orchids—

But as we have seen in so many areas, experience affects whether a gene will be expressed. Experiences such as child abuse can leave tracks in the brain, increasing the chances that a genetic vulnerability to a disorder such as PTSD will be expressed (Mehta et al., 2013; Zannas et al., 2015).

THE BRAIN Anxiety-

Generalized anxiety disorder, panic attacks, phobias, OCD, and PTSD express themselves biologically as overarousal of brain areas involved in impulse control and habitual behaviors. These disorders reflect a brain danger-

NATURAL SELECTION No matter how fearful or fearless we are, we humans seem biologically prepared to fear the threats our ancestors faced—

Compare our easily conditioned fears to what we do not easily learn to fear. World War II air raids, for example, produced remarkably few lasting phobias. As the air strikes continued, the British, Japanese, and German populations did not become more and more panicked. Rather, they grew more indifferent to planes outside their immediate neighborhood (Mineka & Zinbarg, 1996). Evolution has not prepared us to fear bombs dropping from the sky.

Our phobias focus on dangers our ancestors faced. Our compulsive acts typically exaggerate behaviors that helped them survive. Grooming had survival value. Gone wild, it becomes compulsive hair pulling. So too with washing up, which becomes ritual hand washing. And checking territorial boundaries becomes checking and rechecking already locked doors (Rapoport, 1989). Although natural selection shaped our behaviors, when taken to an extreme, these behaviors can interfere with daily life.

Retrieve + Remember

Question 13.10

•Researchers believe that conditioning and cognition are aspects of learning that contribute to anxiety-

ANSWER: Biological factors include inherited temperament differences and other gene variations; experience-