13.4 Major Depressive Disorder and Bipolar Disorder

LOQ 13-

Most of us will have some direct or indirect experience with depression. In the past year, have you at some time “felt so depressed that it was difficult to function”? If so, you were not alone. In one national survey, 31 percent of American college students answered Yes (ACHA, 2009).

The college years are an exciting time, but they can also be stressful. Perhaps you wanted to attend college right out of high school but couldn’t afford it, and now you are struggling to find time for school amid family and work responsibilities. Perhaps social stresses—

Some people’s depression has a seasonal pattern. It regularly returns each fall or winter and departs each spring. For many others, winter darkness simply means more blue moods. When asked “Have you cried today?,” Americans have said Yes more often in the winter.

Depression makes sense from an evolutionary perspective. To feel bad in reaction to very sad events is to be in touch with reality. At such times, depression is like a car’s low-

There is sense to suffering. After reassessing our life, we may redirect our energy in more promising ways. Even mild sadness helps people process and recall faces more accurately (Hills et al., 2011). They also tend to pay more attention to details and make better decisions (Forgas, 2009).

Sometimes, however, depression becomes seriously maladaptive. Abnormal depression can take many forms. Let’s look more closely at two of them—

Major Depressive Disorder

major depressive disorder a disorder in which a person experiences, in the absence of drugs or another medical condition, two or more weeks with five or more symptoms, at least one of which must be either (1) depressed mood or (2) loss of interest or pleasure.

Joy, contentment, sadness, and despair are different points on a continuum, points at which any of us may be found at any given moment. The difference between a blue mood after bad news and major depressive disorder is like the difference between gasping for breath after a hard run and having chronic asthma. Major depressive disorder occurs when at least five signs of depression last two or more weeks (TABLE 13.6). To sense what major depressive disorder feels like, imagine combining the anguish of grief with the exhaustion you feel after pulling an all-

|

The DSM- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Although phobias are more common, depression is the number-

Adults diagnosed with persistent depressive disorder (formerly called dysthymia) have experienced a mildly depressed mood for at least two years (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). They also display at least two of depression’s symptoms.

Bipolar Disorder

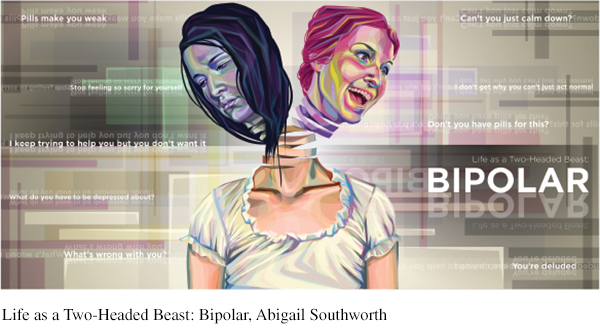

bipolar disorder a disorder in which a person alternates between the hopelessness and weariness of depression and the overexcited state of mania. (Formerly called manic-

mania a hyperactive, wildly optimistic state in which dangerously poor judgment is common.

Our genes dispose some of us, more than others, to respond emotionally to good and bad events (Whisman et al., 2014). In bipolar disorder, people bounce from one emotional extreme to the other (week to week, rather than day to day or moment to moment). When a depressive episode ends, a euphoric, overly talkative, wildly energetic, and extremely optimistic state called mania follows. But before long, the mood either returns to normal or plunges again into depression.

If depression is living in slow motion, mania is fast forward. During mania, people feel little need for sleep, are easily irritated, and show fewer sexual inhibitions. Feeling extreme optimism and self-

In milder forms, mania’s energy and flood of ideas can fuel creativity. Classical composer George Frideric Handel (1685–

Bipolar disorder is much less common than major depressive disorder, but is often more dysfunctional. It afflicts as many men as women. The diagnosis has risen among adolescents, whose mood swings, sometimes prolonged, range from rage to giddiness. In the decade between 1994 and 2003, bipolar diagnoses in under-

Understanding Major Depressive Disorder and Bipolar Disorder

LOQ 13-

From thousands of studies of the causes, treatment, and prevention of major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder, researchers have pulled out some common threads. Here, we focus primarily on major depressive disorder. Any theory of depression must explain a number of findings (Lewinsohn et al., 1985, 1998, 2003).

Behaviors and thoughts change with depression. People trapped in a depressed mood are inactive and feel alone, empty, and without a meaningful future (Bullock & Murray, 2014; Smith & Rhodes, 2014). They are sensitive to negative happenings (Peckham et al., 2010). They recall negative information. And they expect negative outcomes (my team will lose, my grades will fall, my love will fail). When the depression lifts, these behaviors and thoughts disappear. Nearly half the time, people with depression also have symptoms of another disorder, such as anxiety or substance abuse.

Depression is widespread. Worldwide, 300 million people have major depressive or bipolar disorder (Global Burden of Disease, 2015).

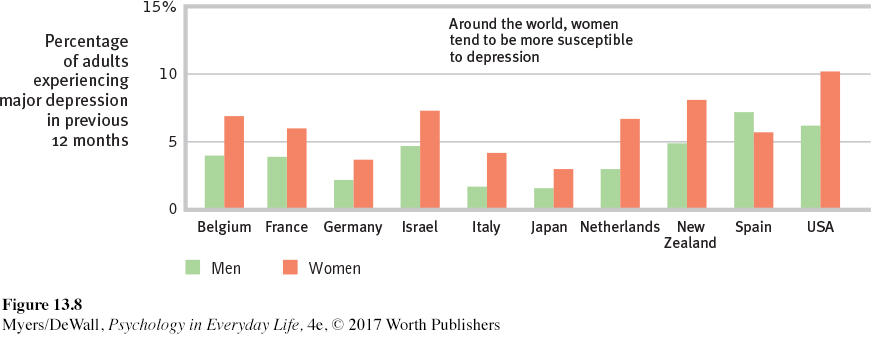

Women’s risk of major depressive disorder is nearly double men’s. In 2009, when Gallup pollsters asked more than a quarter-

million Americans if they had ever been diagnosed with depression, 13 percent of men and 22 percent of women said Yes (Pelham, 2009). When Gallup asked Americans if they experienced sadness “during a lot of the day yesterday,” 17 percent of men and 28 percent of women answered Yes (Mendes & McGeeney, 2012). This depression gender gap has been found worldwide (FIGURE 13.8). The trend begins in adolescence; preadolescent girls are not more depression- prone than boys are (Hyde et al., 2008). The depression gender gap fits a bigger pattern. Women are generally more vulnerable to disorders involving internal states, such as depression, anxiety, and inhibited sexual desire. Women experience more situations that may increase their risk for depression, such as receiving less pay for equal work, juggling multiple roles, and caring for children and elderly family members (Freeman & Freeman, 2013). Men’s disorders tend to be more external—

alcohol use disorder, antisocial conduct, lack of impulse control. When women get sad, they often get sadder than men do. When men get mad, they often get madder than women do.  Figure 13.8: FIGURE 13.8 Gender and major depressive disorder Interviews with 89,037 adults in 18 countries (10 of which are shown here) confirm what many smaller studies have found. Women’s risk of major depressive disorder is nearly double that of men’s. (Data from Bromet et al., 2011.)

Figure 13.8: FIGURE 13.8 Gender and major depressive disorder Interviews with 89,037 adults in 18 countries (10 of which are shown here) confirm what many smaller studies have found. Women’s risk of major depressive disorder is nearly double that of men’s. (Data from Bromet et al., 2011.)Most major depressive episodes end on their own. Although therapy often speeds recovery, most people recover from depression and return to normal even without professional help. The black cloud of depression comes and, a few weeks or months later, it often goes. For about half of these people, it eventually returns (Burcusa & Iacono, 2007; Curry et al., 2011; Hardeveld et al., 2010). For about 20 percent, the condition will be chronic (Klein, 2010). An enduring recovery is more likely if the first episode strikes later in life, there were few previous episodes, the person experiences minimal stress, and there is ample social support (Fergusson & Woodward, 2002; Kendler et al., 2001; Richards, 2011).

Stressful events sometimes precede depression. As anxiety is a response to the threat of future loss, depression is often a response to past and current loss. A significant loss or trauma—

a loved one’s death, a lost job, a marriage break- up, or a physical assault— increase one’s risk of depression (Kendler et al., 2008; Monroe & Reid, 2009; Orth et al., 2009). So does moving to a new culture, especially for young people who have not yet formed an identity (Zhang et al., 2013). One long- term study tracked rates of depression in 2000 people (Kendler, 1998). Among those who had experienced no stressful life event in the preceding month, the risk of depression was less than 1 percent. Among those who had experienced three such events in that month, the risk was 24 percent. Surveys before and after Hurricane Sandy in 2012 revealed a 25 percent increase in clinical depression rates in the most affected areas (Witters & Ander, 2013). But life’s daily minor stressors can also take a toll. One study showed that overreacting to minor stressful events (such as a broken appliance) was a good predictor of depression a decade later (Charles et al., 2013). Page 397 LIFE AFTER DEPRESSION J. K. Rowling, author of the Harry Potter books, reported suffering acute depression—

LIFE AFTER DEPRESSION J. K. Rowling, author of the Harry Potter books, reported suffering acute depression—a “dark time,” with suicidal thoughts— between ages 25 and 28. It was a “terrible place,” she said, but it formed a foundation that allowed her “to come back stronger” (McLaughlin, 2010). Terry Gatanis/Globe Photos/ZUMAPRESS.com/ Newscom With each new generation, depression is striking earlier in life (now often in the late teens) and affecting more people. This has been true in Canada, England, France, Germany, Italy, Lebanon, New Zealand, Puerto Rico, Taiwan, and the United States (Collishaw et al., 2007; Cross-

National Collaborative Group, 1992; Kessler et al., 2010; Twenge et al., 2008). In North America, today’s young adults are three times more likely than their grandparents to report having recently— or ever— suffered depression. This is true even though their grandparents have been at risk for many more years. The increased risk among young adults appears partly real, but it may also reflect increased reporting due to cultural differences. Today’s young people are more willing to talk openly about their depression. Psychological processes may also contribute. Studies of aging and memory show that we tend to forget many negative experiences over time. Older generations may report fewer instances of depression in part because they overlook depressed feelings they had in earlier years.

Armed with facts, today’s researchers propose biological and cognitive explanations of depression, often combined in a biopsychosocial perspective.

For a 9-

For a 9-

Biological Influences

Depression is a whole-

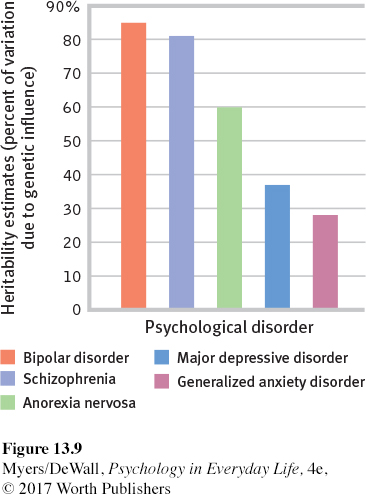

GENES AND DEPRESSION Major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder run in families. The risk of being diagnosed with one of these disorders increases if your parent or sibling has the disorder (Sullivan et al., 2000). If one identical twin is diagnosed with major depressive disorder, the chances are about 1 in 2 that at some time the other twin will be, too. If one identical twin has bipolar disorder, the chances of a similar diagnosis for the co-

To tease out the genes that put people at risk for depression, some researchers have turned to linkage analysis. After finding families in which the disorder appears across several generations, geneticists examine DNA from affected and unaffected family members, looking for differences. Linkage analysis points us to a chromosome neighborhood, note researchers; “a house-

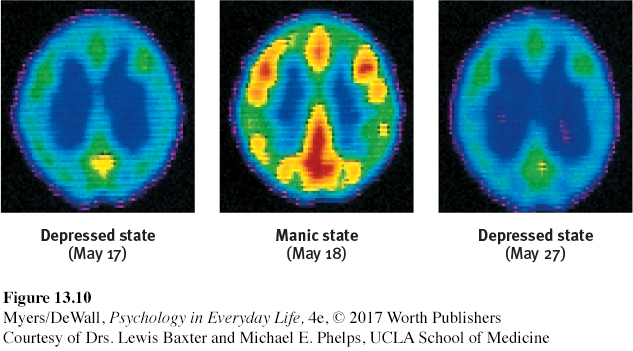

THE DEPRESSED BRAIN Scanning devices let us eavesdrop on the brain’s activity. During depression, brain activity slows. During mania, it increases (FIGURE 13.10). Depression can cause the brain’s reward centers to become less active (Miller et al., 2015; Stringaris et al., 2015). During positive emotions, reward centers become more active (Davidson et al., 2002; Heller et al., 2009; Robinson et al., 2012).

At least two neurotransmitter systems are at work during these periods of brain inactivity and hyperactivity. Norepinephrine increases arousal and boosts mood. It is scarce during depression and overabundant during mania. Serotonin is also scarce or inactive during depression (Carver et al., 2008).

In Chapter 14, we will see how drugs that relieve depression tend to make more norepinephrine or serotonin available to the depressed brain. Repetitive physical exercise, such as jogging, which increases serotonin, can have a similar effect (Ilardi, 2009; Jacobs, 1994). To run away from a bad mood, you can sometimes use your own two feet.

Psychological and Social Influences

Biological influences contribute to depression, but as we have so often seen, nature and nurture interact. Our life experiences—

Thinking matters, too. The social-

I [despaired] of ever being human again. I honestly felt subhuman, lower than the lowest vermin. Furthermore, I . . . could not understand why anyone would want to associate with me, let alone love me. . . . I was positive that I was a fraud and a phony and that I didn’t deserve my Ph.D. . . . I didn’t deserve the research grants I had been awarded; I couldn’t understand how I had written books and journal articles. . . . I must have conned a lot of people.

Expecting the worst, depressed people magnify bad experiences and minimize good ones (Wenze et al., 2012). Their self-

NEGATIVE THOUGHTS AND NEGATIVE MOODS INTERACT Self-

Why are women nearly twice as vulnerable to depression (Kessler, 2001)? This higher risk may relate to women’s tendency to ruminate—to overthink, fret, or brood (Nolen-

Even so, why do life’s unavoidable failures lead only some people to become depressed? The answer lies partly in their explanatory style—

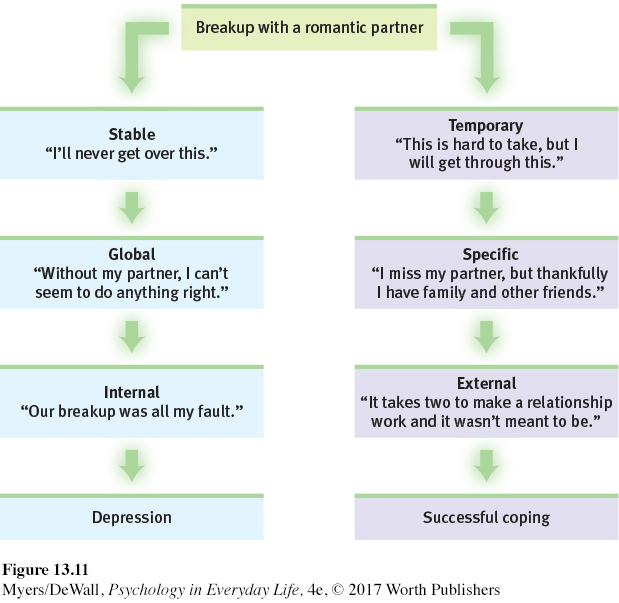

Depressed people tend to blame themselves. As FIGURE 13.11 illustrates, they explain bad events in terms that are stable (“I’ll never get over this”), global (“I can’t do anything right”), and internal (“It’s all my fault”). Their explanations are pessimistic, overgeneralized, self-

Critics point out a chicken-

DEPRESSION’S VICIOUS CYCLE Depression, social withdrawal, and rejection feed one another. Depression, as we have seen, is often brought on by events that disrupt our sense of who we are and why we are worthy human beings. Such disruptions in turn lead to brooding, which is rich soil for growing negative feelings. And that negativity—

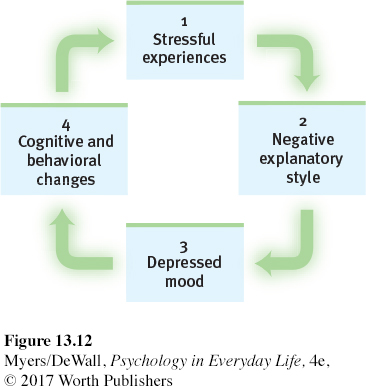

We can now assemble pieces of the depression cycle (FIGURE 13.12): (1) Stressful experiences interpreted through (2) a brooding, negative explanatory style create (3) a hopeless, depressed state that (4) hampers the way the person thinks and acts. These thoughts and actions in turn fuel (1) further stressful experiences such as rejection. Depression is a snake that bites its own tail.

It is a cycle we can all recognize. When we feel down, we think negatively and remember bad experiences. Britain’s Prime Minister Winston Churchill called depression a “black dog” that periodically hounded him. President Abraham Lincoln was so withdrawn and brooding as a young man that his friends feared he might take his own life (Kline, 1974). As their lives remind us, people can and do struggle through depression. Most regain their capacity to love, to work, to hope, and even to succeed at the highest levels.

Suicide and Self-Injury

LOQ 13-

Each year over 800,000 despairing people worldwide will elect a permanent solution to what might have been a temporary problem (WHO, 2014b). The risk of suicide is at least five times greater for those who have been depressed than for the general population (Bostwick & Pankratz, 2000). People seldom elect suicide while in the depths of depression, when energy and will are lacking. The risk increases when they begin to rebound and become capable of following through (Chu et al., 2016).

Suicide is not necessarily an act of hostility or revenge. People—

Looking back, families and friends may recall signs that they believe should have forewarned them—

How can we be helpful to someone who is talking suicide—

Nonsuicidal Self-Injury

Suicide is not the only way to send a message or deal with distress. Some people may engage in nonsuicidal self-

Why do people hurt themselves? They tend to experience bullying and harassment (van Geel et al., 2015). They are generally less able to tolerate and regulate emotional distress (Hamza et al., 2015). They are often extremely self-

gain relief from intense negative thoughts through the distraction of pain.

attract attention and possibly get help.

relieve guilt by punishing themselves.

get others to change their negative behavior (bullying, criticism).

fit in with a peer group.

Does NSSI lead to suicide? Usually not. Those who engage in NSSI are typically suicide gesturers, not suicide attempters (Nock & Kessler, 2006). Suicide gesturers engage in NSSI as a desperate but non-

Retrieve + Remember

Question 13.17

•What does it mean to say that “depression is a whole-

ANSWER: Many factors contribute to depression, including the biological influences of genetics and brain function. Social-