3.3 Infancy and Childhood

maturation biological growth processes leading to orderly changes in behavior, mostly independent of experience.

As a flower develops in accord with its genetic instructions, so do we humans. Maturation—the orderly sequence of biological growth—

Physical Development

LOQ 3-

Brain Development

In your mother’s womb, your developing brain formed nerve cells at the explosive rate of nearly one-

From ages 3 to 6, the most rapid brain growth was in your frontal lobes, the seat of reasoning and planning. During those years, your ability to control your attention and behavior developed rapidly (Garon et al., 2008; Thompson-

“It is a rare privilege to watch the birth, growth, and first feeble struggles of a living human mind.”

Annie Sullivan, in Helen Keller’s The Story of My Life, 1903

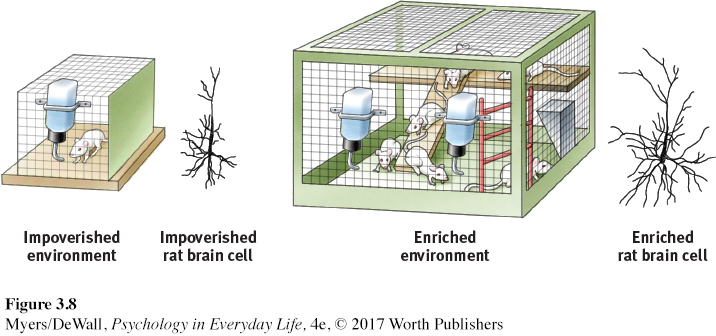

Your genes laid down the basic design of your brain, rather like the lines of a coloring book. Experience fills in the details (Kenrick et al., 2009). So how do early experiences shape the brain? Some fascinating experiments separated young rats into two groups (Renner & Rosenzweig, 1987; Rosenzweig, 1984). Rats in one group lived alone, with little to interest or distract them. The other rats shared a cage, complete with objects and activities that might exist in a natural “rat world” (FIGURE 3.8). Compared with the “loner” rats, those that lived in an enriched environment developed a heavier and thicker brain cortex.

The environment’s effect was so great that if you viewed brief video clips, you could tell from the rats’ activity and curiosity whether they had lived in solitary confinement or in the enriched setting (Renner & Renner, 1993). After 60 days in the enriched environment, some rats’ brain weight increased 7 to 10 percent. The number of synapses, forming the networks between the cells (see FIGURE 3.8), mushroomed by about 20 percent (Kolb & Whishaw, 1998). The enriched environment literally increased brain power.

Touching or massaging infant rats and premature human babies has similar benefits (Field, 2010; Sarro et al., 2014). In hospital intensive care units, medical staff now massage premature infants to help them develop faster neurologically, gain weight more rapidly, and go home sooner. Preemies who have had skin-

Nature and nurture interact to sculpt our synapses. Brain maturation provides us with a wealth of neural connections. Experience—

critical period a period early in life when exposure to certain stimuli or experiences is needed for proper development.

During early childhood—

The brain’s development does not, however, end with childhood. Throughout life, whether we are learning to text friends or write textbooks, we perform with increasing skill as our learning changes our brain tissue (Ambrose, 2010).

Motor Development

Babies gain control over their movements as their nervous system and muscles mature. Motor skills emerge, and with occasional exceptions, their sequence is universal. Babies roll over before they sit unsupported. They usually crawl before they walk. The recommended infant back-

There are, however, individual differences in timing. Consider walking. In the United States, 90 percent of all babies walk by age 15 months. But 25 percent walk by 11 months, and 50 percent within a week after their first birthday (Frankenburg et al., 1992). In some regions of Africa, the Caribbean, and India, caregivers often massage and exercise babies. This can speed up the process of learning to walk (Karasik et al., 2010).

Genes guide motor development. Identical twins typically begin walking on nearly the same day (Wilson, 1979). The rapid development of the cerebellum (at the back of the brain; see Chapter 2) helps create our eagerness to walk at about age 1. Maturation is likewise important for mastering other physical skills, including bowel and bladder control. Before a child’s muscles and nerves mature, no amount of pleading or punishment will produce successful toilet training.

Retrieve + Remember

Question 3.7

•The biological growth process, called _______, explains why most children begin walking by about 12 to 15 months.

ANSWER: maturation

Brain Maturation and Infant Memory

Can you recall your third birthday party? Most people cannot. Psychologists call this blank space in our conscious memory infantile amnesia. Although we consciously recall little from before age 4, our brain was processing and storing information during that time. How do we know that? To see how developmental psychologists study thinking and learning in very young children, consider a surprise discovery.

In 1965, Carolyn Rovee-

Thinking about her unintended home experiment, Rovee-

Traces of forgotten childhood languages may also persist. One study tested English-

Cognitive Development

LOQ 3-

cognition all the mental activities associated with thinking, knowing, remembering, and communicating.

Somewhere on your journey from egghood to childhood, you became conscious. When was that? Psychologist Jean Piaget [pee-

Piaget’s interest in children’s cognitive development began in 1920, when he was developing questions for children’s intelligence tests in Paris. Looking over the test results, Piaget noticed something interesting. At certain ages, children made strikingly similar mistakes. Where others saw childish mistakes, Piaget saw intelligence at work.

Piaget’s studies led him to believe that a child’s mind develops through a series of stages. This upward march begins with the newborn’s simple reflexes, and it ends with the adult’s abstract reasoning power. Moving through these stages, Piaget believed, is like climbing a ladder. A child can’t easily move to a higher rung without first having a firm footing on the one below.

Tools for thinking and reasoning differ in each stage. Thus, you can tell an 8-

schema a concept or framework that organizes and interprets information.

Piaget believed that the force driving us up this intellectual ladder is our struggle to make sense of our experiences. His core idea was that “children are active thinkers, constantly trying to construct more advanced understandings of the world” (Siegler & Ellis, 1996). Part of this active thinking is building schemas, which are concepts or mental molds into which we pour our experiences.

assimilation interpreting our new experiences in terms of our existing schemas.

accommodation adapting our current understandings (schemas) to incorporate new information.

To explain how we use and adjust our schemas, Piaget proposed two more concepts. First, we assimilate new experiences—

Piaget’s Theory and Current Thinking

Piaget believed that children construct their understanding of the world as they interact with it. Their minds go through spurts of change, he believed, followed by greater stability as they move from one level to the next. In his view, cognitive development consisted of four major stages—

sensorimotor stage in Piaget’s theory, the stage (from birth to nearly 2 years of age) during which infants know the world mostly in terms of their sensory impressions and motor activities.

SENSORIMOTOR STAGE The sensorimotor stage begins at birth and lasts to nearly age 2. In this stage, babies take in the world through their senses and actions—

object permanence the awareness that things continue to exist even when not perceived.

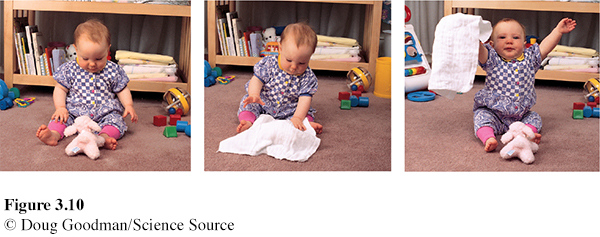

Very young babies seem to live in the present. Out of sight is out of mind. In one test, Piaget showed an infant an appealing toy and then flopped his hat over it. Before the age of 6 months, the infant acted as if the toy no longer existed. Young infants lack object permanence—the awareness that objects continue to exist when out of sight (FIGURE 3.10). By about 8 months, infants begin to show that they do remember things they can no longer see. If you hide a toy, an 8-

So does object permanence in fact blossom suddenly at 8 months, much as tulips blossom in spring? Today’s researchers think not. They believe object permanence unfolds gradually, and they view development as more continuous than Piaget did.

They also think that young children are more competent than Piaget and his followers believed. Young children think like little scientists, testing ideas and learning from patterns (Gopnik et al., 2015). For example, infants seem to have an inborn grasp of simple physical laws—

preoperational stage in Piaget’s theory, the stage (from about 2 to 6 or 7 years of age) in which a child learns to use language but cannot yet perform the mental operations of concrete logic.

PREOPERATIONAL STAGE Piaget believed that until about age 6 or 7, children are in a preoperational stage—able to represent things with words and images, but too young to perform mental operations (such as imagining an action and mentally reversing it).

conservation the principle (which Piaget believed to be a part of concrete operational reasoning) that properties such as mass, volume, and number remain the same despite changes in shapes.

Conservation Consider a 5-

Pretend Play A child who can think in symbols can begin to enjoy pretend play. Although Piaget did not view the change from one stage to another as an abrupt shift, symbolic thinking occurs at an earlier age than he supposed. One researcher showed children a model of a room and hid a miniature stuffed dog behind its miniature couch (DeLoache & Brown, 1987). The 2½-year-

For quick video examples of children being tested for conservation, visit LaunchPad’s Concept Practice: Piaget and Conservation.

For quick video examples of children being tested for conservation, visit LaunchPad’s Concept Practice: Piaget and Conservation.

egocentrism in Piaget’s theory, the preoperational child’s difficulty taking another’s point of view.

Egocentrism Piaget also taught us that preschool children are egocentric: They have difficulty imagining things from another’s point of view. Asked to “show Mommy your picture,” 2-

theory of mind people’s ideas about their own and others’ mental states—

Theory of Mind When Little Red Riding Hood realized her “grandmother” was really a wolf, she swiftly revised her ideas about the creature’s intentions and raced away. Preschoolers develop this ability to read others’ mental states when they begin forming a theory of mind.

When children can imagine another person’s viewpoint, all sorts of new skills emerge. They can tease, because they now understand what makes a playmate angry. They may be able to convince a sibling to share. Knowing what might make a parent buy a toy, they may try to persuade. Children who have an advanced ability to understand others’ minds tend to be more popular (Slaughter et al., 2015).

Between about ages 3 and 4½, children worldwide use their new theory-

autism spectrum disorder (ASD) a disorder that appears in childhood and is marked by significant deficiencies in communication and social interaction, and by rigidly fixated interests and repetitive behaviors.

Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) have an impaired theory of mind (Rajendran & Mitchell, 2007; Senju et al., 2009). They have difficulty reading and remembering other people’s thoughts and feelings. Most children learn that another child’s pouting mouth signals sadness, and that twinkling eyes mean happiness or mischief. A child with ASD fails to understand these signals (Boucher et al., 2012; Frith & Frith, 2001).

ASD has differing levels of severity. “High-

Biological factors, including genetic influences and abnormal brain development, contribute to ASD (Blanken et al., 2015; Colvert et al., 2015; Makin, 2015a). Childhood measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccinations do not (Demicheli et al., 2012). Based on a fraudulent 1998 study—

ASD afflicts about four boys for every girl (Lai et al., 2015). Children exposed to high levels of the male sex hormone testosterone in the womb may develop more masculine and ASD-

Why is reading faces so difficult for those with ASD? The underlying cause seems to be poor communication among brain regions that normally work together to let us take another’s viewpoint. This effect appears to result from ASD-

concrete operational stage in Piaget’s theory, the stage of cognitive development (from about 7 to 11 years of age) during which children gain the mental operations that enable them to think logically about concrete events.

CONCRETE OPERATIONAL STAGE By about age 7, said Piaget, children enter the concrete operational stage. Given concrete (physical) materials, they begin to grasp conservation. Understanding that change in form does not mean change in quantity, they can mentally pour milk back and forth between glasses of different shapes. They also enjoy jokes that allow them to use this new understanding:

Mr. Jones went into a restaurant and ordered a whole pizza for his dinner. When the waiter asked if he wanted it cut into 6 or 8 pieces, Mr. Jones said, “Oh, you’d better make it 6, I could never eat 8 pieces!” (McGhee, 1976)

Piaget believed that during the concrete operational stage, children become able to understand simple math and conservation. When my [DM’s] daughter, Laura, was 6, I was astonished at her inability to reverse simple arithmetic. Asked, “What is 8 plus 4?” she required 5 seconds to compute “12,” and another 5 seconds to then compute 12 minus 4. By age 8, she could answer a reversed question instantly.

formal operational stage in Piaget’s theory, the stage of cognitive development (normally beginning about age 12) during which people begin to think logically about abstract concepts.

FORMAL OPERATIONAL STAGE By age 12, said Piaget, our reasoning expands to include abstract thinking. We are no longer limited to purely concrete reasoning, based on actual experience. As children approach adolescence, many become capable of abstract if . . . then thinking: If this happens, then that will happen. Piaget called this new systematic reasoning ability formal operational thinking. (Stay tuned for more about adolescents’ thinking abilities later in this chapter.) TABLE 3.1 summarizes the four stages in Piaget’s theory.

| Typical Age Range | Stage and Description | Key Accomplishments |

|---|---|---|

| Birth to nearly 2 years |

Sensorimotor Experiencing the world through senses and actions (looking, hearing, touching, mouthing, and grasping) |

|

| About 2 to 6 or 7 years |

Preoperational Representing things with words and images; using intuitive rather than logical reasoning |

|

| About 7 to 11 years |

Concrete operational Thinking logically about concrete events; grasping concrete analogies and performing arithmetical operations |

|

| About 12 through adulthood |

Formal operational Reasoning abstractly |

|

An Alternative Viewpoint: Vygotsky and the Social Child

As Piaget was forming his theory of cognitive development, Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky was also studying how children think and learn. He noted that by age 7, children are more able to think and solve problems with words. They do this, he said, by no longer thinking aloud. Instead they internalize their culture’s language and rely on inner speech (Fernyhough, 2008). Parents who say “No, no, Bevy!” when pulling her hand away from a cake are giving their child a self-

Piaget emphasized how the child’s mind grows through interaction with the physical environment. Vygotsky emphasized how the child’s mind grows through interaction with the social environment. If Piaget’s child was a young scientist, Vygotsky’s was a young apprentice. By guiding children and giving them new words, parents and others provide a temporary scaffold from which children can step to higher levels of thinking (Renninger & Granott, 2005). Language is an important ingredient of social guidance, and it provides the building blocks for thinking, noted Vygotsky. (For more on children’s development of language, see Chapter 8.)

Reflecting on Piaget’s Theory

What remains of Piaget’s ideas about the child’s mind? Plenty. Time magazine singled him out as one of the twentieth century’s 20 most influential scientists and thinkers. And a survey of British psychologists rated him as the last century’s greatest psychologist (The Psychologist, 2003). Piaget identified significant cognitive milestones and stimulated worldwide interest in how the mind develops. His emphasis was less on the ages at which children typically reach specific milestones than on their sequence. Studies around the globe, from Algeria to North America, have confirmed that human cognition unfolds basically in the sequence Piaget described (Lourenco & Machado, 1996; Segall et al., 1990).

However, today’s researchers see development as more continuous than did Piaget. By detecting the beginnings of each type of thinking at earlier ages, they have revealed conceptual abilities Piaget missed. Moreover, they see formal logic as a smaller part of cognition than he did. Piaget would not be surprised that today, as part of our own cognitive development, we are adapting his ideas to accommodate new findings.

Piaget’s insights can nevertheless help teachers and parents understand young children. Remember this: Young children cannot think with adult logic and cannot take another’s viewpoint. What seems simple and obvious to us—

For a 7-

For a 7-

Retrieve + Remember

Question 3.8

•Object permanence, pretend play, conservation, and abstract logic are developmental milestones for which of Piaget’s stages, respectively?

ANSWER: Object permanence for the sensorimotor stage, pretend play for the preoperational stage, conservation for the concrete operational stage, and abstract logic for the formal operational stage.

Question 3.9

•Match each developmental ability (1–

Sensorimotor

Preoperational

Concrete operational

Formal operational

Thinking about abstract concepts, such as “freedom.”

Enjoying imaginary play (such as dress-

up). Understanding that physical properties stay the same even when objects change form.

Having the ability to reverse math operations.

Understanding that something is not gone for good when it disappears from sight, as when Mom “disappears” behind the shower curtain.

Having difficulty taking another’s point of view (as when blocking someone’s view of the TV).

ANSWERS: 1. d, 2. b, 3. c, 4. c, 5. a, 6. b

Social Development

stranger anxiety the fear of strangers that infants commonly display, beginning by about 8 months of age.

From birth, babies all over the world are normally very social creatures, developing an intense bond with their caregivers. Infants come to prefer familiar faces and voices, then to coo and gurgle when given their mother’s or father’s attention. Have you ever wondered why tiny infants can happily be handed off to admiring visitors, but after a certain age pull back? By about 8 months, soon after object permanence emerges and children become mobile, a curious thing happens: They develop stranger anxiety. When handed to a stranger they may cry and reach for a parent: “No! Don’t leave me!” At about this age, children have schemas for familiar faces—

Origins of Attachment

LOQ 3-

attachment an emotional tie with another person; shown in young children by their seeking closeness to their caregiver and showing distress on separation.

One-

Infants normally become attached to people—

During the 1950s, University of Wisconsin psychologists Harry Harlow and Margaret Harlow bred monkeys for their learning studies. Shortly after birth, they separated the infants from their mothers and placed each infant in an individual cage with a cheesecloth baby blanket (Harlow et al., 1971). Then came a surprise: When their soft blankets were taken to be washed, the infant monkeys became distressed.

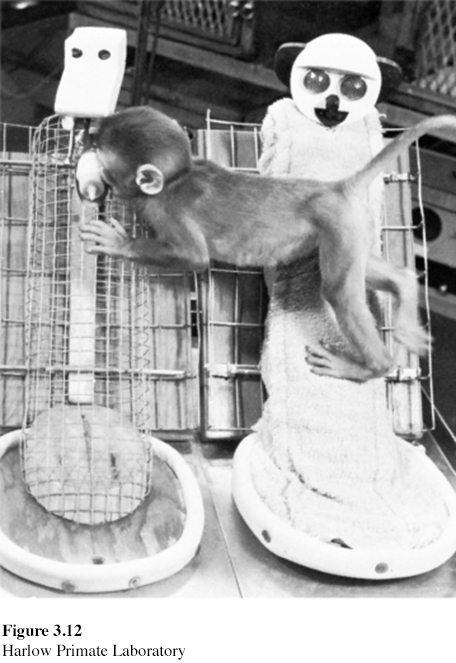

Imagine yourself as one of the Harlows, trying to figure out why the monkey infants were so intensely attached to their blankets. Psychologists believed that infants became attached to those who nourish them. Might comfort instead be the key? How could you test that idea? The Harlows decided to pit the drawing power of a food source against the contact comfort of the blanket by creating two artificial mothers. One was a bare wire cylinder with a wooden head and an attached feeding bottle. The other was a cylinder wrapped with terry cloth.

For the monkeys, it was no contest. They overwhelmingly preferred the comfy cloth mother (FIGURE 3.12). Like anxious infants clinging to their live mothers, the monkey babies would cling to their cloth mothers when anxious. When exploring their environment, they used her as a secure base. They acted as though they were attached to her by an invisible elastic band that stretched only so far before pulling them back. Researchers soon learned that other qualities—

Human infants, too, become attached to parents who are soft and warm and who rock, pat, and feed. Much parent-

Attachment Differences

LOQ 3-

Children’s attachments differ. To study these differences, Mary Ainsworth (1979) designed the strange situation experiment. She observed mother-

Other infants show insecure attachment, marked by either anxiety or avoidance of trusting relationships. These infants are less likely to explore their surroundings. Anxiously attached infants may cling to their mother. When she leaves, they might cry loudly and remain upset. Avoidantly attached infants seem not to notice or care about her departure and return (Ainsworth, 1973, 1989; Kagan, 1995; van IJzendoorn & Kroonenberg, 1988).

Ainsworth and others found that sensitive, responsive mothers—

Today’s climate of greater respect for animal welfare would prevent primate studies like the Harlows’. Many now remember Harry Harlow as the researcher who tortured helpless monkeys. But others support the Harlows’ work. “Harry Harlow, whose name has [come to mean] cruel monkey experiments, actually helped put an end to cruel child-

So caring parents matter. But is attachment style the result of parenting? Or are other factors also at work?

TEMPERAMENT AND ATTACHMENT How does temperament—

Some babies tend to be difficult—

One researcher’s solution was to randomly assign 100 temperamentally difficult infants to two groups. Half of the 6-

Children’s anxiety over separation from parents peaks at around 13 months, then gradually declines (Kagan, 1976). This happens whether they live with one parent or two, are cared for at home or in day care, live in North America, Guatemala, or the Kalahari Desert. As the power of early attachment relaxes, we humans begin to move out into a wider range of situations. We communicate with strangers more freely. And we stay attached emotionally to loved ones despite distance.

At all ages, we are social creatures. But as we mature, our secure base and safe haven shift—

Consider how researchers have studied temperament and personality with LaunchPad’s IMMERSIVE LEARNING: How Would You Know If Personality Runs in the Genes?

Consider how researchers have studied temperament and personality with LaunchPad’s IMMERSIVE LEARNING: How Would You Know If Personality Runs in the Genes?

basic trust according to Erik Erikson, a sense that the world is predictable and trustworthy; said to be formed during infancy by appropriate experiences with responsive caregivers.

ATTACHMENT STYLES AND LATER RELATIONSHIPS Developmental psychologist Erik Erikson (1902–

Do our early attachments form the foundation for adult relationships, including our comfort with intimacy? Many researchers now believe they do (Birnbaum et al., 2006; Fraley et al., 2013). People who report that they had secure relationships with their parents tend to enjoy secure friendships (Gorrese & Ruggieri, 2012). Children with secure, responsive mothers tend to have good grades and strong friendships (Raby et al., 2014).

Feeling insecurely attached to others during childhood may take either of two main forms (Fraley et al., 2011). One is anxiety, in which people constantly crave acceptance but are overly alert to signs of possible rejection. The other is avoidance, in which people experience discomfort getting close to others and tend to keep their distance. An anxious attachment style can annoy relationship partners. An avoidant style decreases commitment and increases conflict (DeWall et al., 2011; Li & Chan, 2012).

Deprivation of Attachment

If secure attachment fosters social trust, what happens when circumstances prevent a child from forming any attachments? In all of psychology, there is no sadder research literature. Some of these babies were raised in institutions without a regular caregiver’s stimulation and attention. Others were locked away at home under conditions of abuse or extreme neglect. Most were withdrawn, frightened, even speechless. Those abandoned in Romanian orphanages during the 1980s looked “frighteningly like Harlow’s monkeys” (Carlson, 1995). The longer they were institutionalized, the more they bore lasting emotional scars (Chisholm, 1998; Nelson et al., 2009).

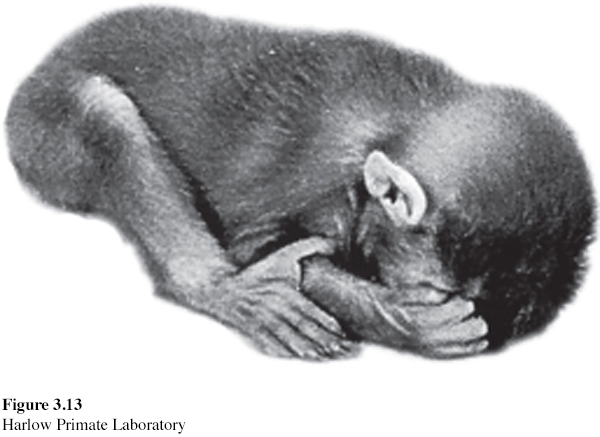

The Harlows’ monkeys bore similar scars if raised in total isolation, without even an artificial mother. As adults, when placed with other monkeys their age, they either cowered in fright or lashed out in aggression. When they reached sexual maturity, most were incapable of mating. Females who did have babies were often neglectful, abusive, even murderous toward them.

In humans, too, the unloved sometimes become the unloving. Some 30 percent of those who have been abused do later abuse their own children. This is four times the U.S. national rate of child abuse (Dumont et al., 2007; Widom, 1989a,b). Abuse victims have a doubled risk of later depression (Nanni et al., 2012). They are especially at risk for depression if they carry a gene variation that spurs stress-

Recall that, depending on our experience, genes may or may not be expressed (active). Epigenetics studies show that experience puts molecular marks on genes that influence their expression. Severe child abuse, for example, can affect the expression of genes (Romens et al., 2015). Extreme childhood trauma can also leave footprints on the brain. Normally placid golden hamsters that are repeatedly threatened and attacked while young grow up to be cowards when caged with same-

Still, many children successfully survive abuse. It’s true that most abusive parents—

Parenting Styles

LOQ 3-

Child-

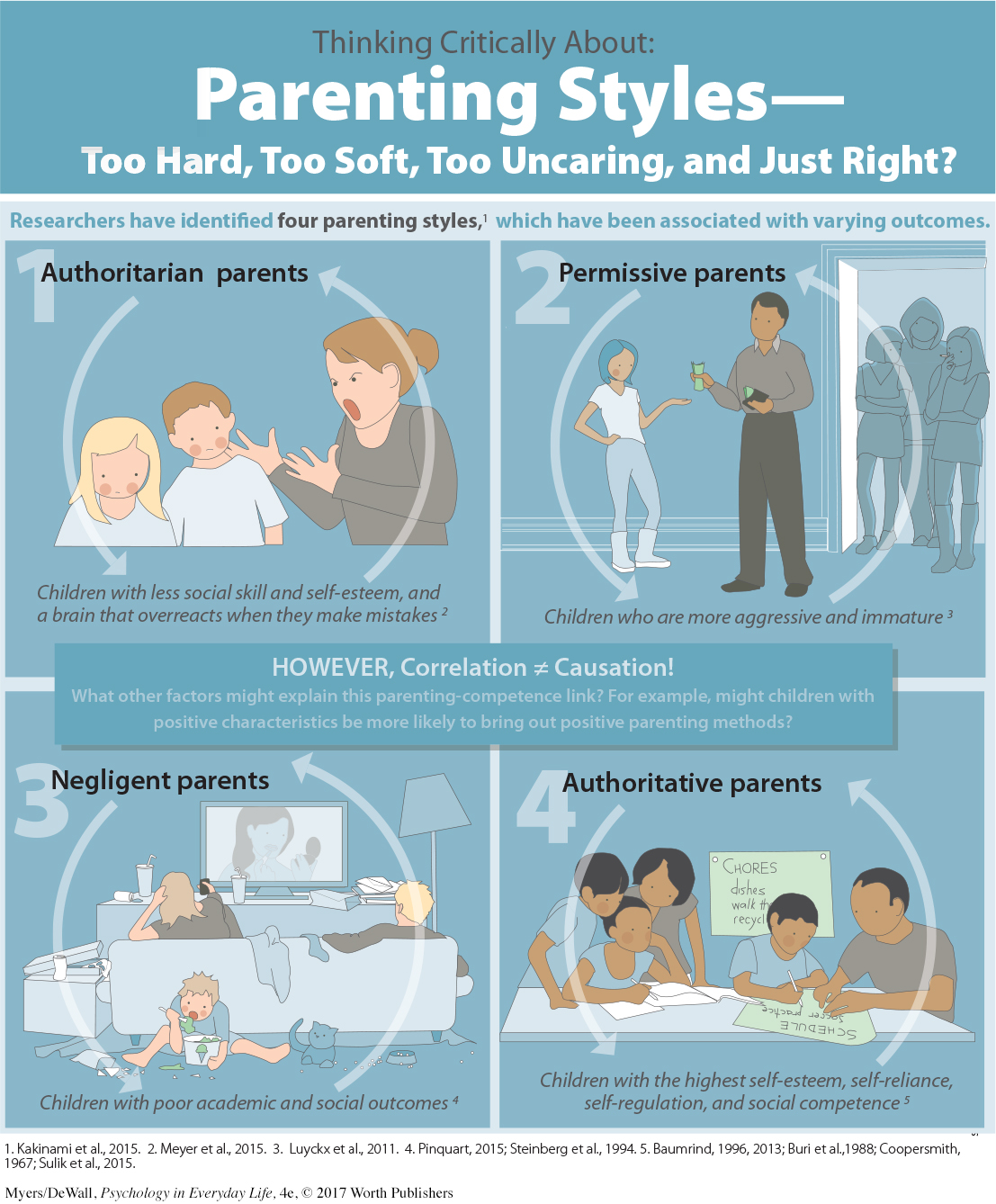

The most heavily researched aspect of parenting has been how, and to what extent, parents seek to control their children. Parenting styles can be described as a combination of two traits: how responsive and how demanding parents are (Kakinami et al., 2015). Investigators have identified four parenting styles (Baumrind, 1966, 1967; Steinberg, 2001):

Authoritarian parents are coercive. They set the rules and expect obedience: “Don’t interrupt.” “Keep your room clean.” “Don’t stay out late or you’ll be grounded.” “Why? Because I said so.”

Permissive parents are unrestraining. They make few demands and use little punishment. They may be unwilling to set limits.

Negligent parents are uninvolved. They are neither demanding nor responsive. They are careless, inattentive, and do not seek a close relationship with their children.

Authoritative parents are confrontive. They are both demanding and responsive. They exert control by setting rules, but especially with older children, they encourage open discussion and allow exceptions.

For more on parenting styles and their associated outcomes, see Thinking Critically About: Parenting Styles.

Remember, too, that parenting doesn’t happen in a vacuum. One of the forces that influences parenting styles is culture.

CULTURE AND CHILD RAISING Culture, as we noted in Chapter 1, is the set of enduring behaviors, ideas, attitudes, values, and traditions shared by a group of people and handed down from one generation to the next (Brislin, 1988). In Chapter 4, we’ll explore the effects of culture on gender. In later chapters, we’ll consider the influence of culture on social interactions and psychological disorders. For now, let’s look at the way that child-

Cultural values vary from place to place and, even in the same place, from one time to another. Do you prefer children who are independent, or children who comply with what others think? The Westernized culture of the United States today favors independence. “You are responsible for yourself,” Western families and schools tell their children. “Follow your conscience. Be true to yourself. Discover your gifts.” In recent years, some Western parents have gone further, telling their children, “You are more special than other children” (Brummelman et al., 2015). Western cultural values used to place greater priority on obedience, respect, and sensitivity to others (Alwin, 1990; Remley, 1988). “Be true to your traditions,” parents then taught their children. “Be loyal to your heritage and country. Show respect toward your parents and other superiors.” Cultures can change.

Children across place and time have thrived under various child-

See LaunchPad’s Video: Correlational Studies for a helpful tutorial animation about correlational research design.

See LaunchPad’s Video: Correlational Studies for a helpful tutorial animation about correlational research design.

Many Asian and African cultures place less value on independence and more on a strong sense of family self. They feel that what shames the child shames the family, and what brings honor to the family brings honor to the self. These cultures also value emotional closeness, and infants and toddlers may sleep with their mothers and spend their days close to a family member (Morelli et al., 1992; Whiting & Edwards, 1988). Sending children away would have been shocking to a traditional African Gusii family. Their babies nursed freely but spent most of the day on their mother’s or siblings’ back, with lots of body contact but little face-

LOQ 3-

Retrieve + Remember

Question 3.10

•The four parenting styles may be described as “too hard, too soft, too uncaring, and just right.” Which parenting style goes with which of these descriptions, and why?

ANSWER: The authoritarian style would be described as too hard, the permissive style too soft, the negligent style too uncaring, and the authoritative style just right. Parents using the authoritative style tend to have children with high self-