6.4 Biology, Cognition, and Learning

From drooling dogs, running rats, and pecking pigeons, we have learned much about the basic processes of learning. But conditioning principles don’t tell us the whole story. Once again we see one of psychology’s big ideas at work. Our learning is the product of the interaction of biological, psychological, and social-

Biological Limits on Conditioning

LOQ 6-

biological constraints evolved biological tendencies that predispose animals’ behavior and learning. Thus, certain behaviors are more easily learned than others.

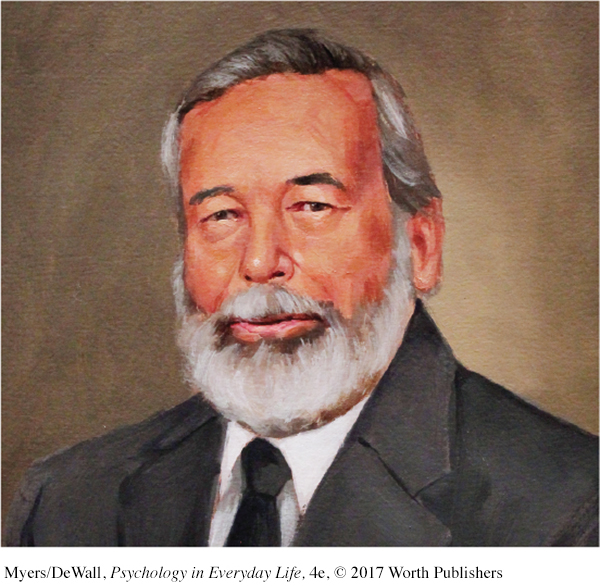

Evolutionary theorist Charles Darwin proposed that natural selection favors traits that aid survival. In the middle of the twentieth century, researchers further showed that there are biological constraints (limits) on learning. Each species comes predisposed (biologically prepared) to learn those things crucial to its survival.

Limits on Classical Conditioning

A discovery by John Garcia and Robert Koelling in the 1960s helped end a popular and widely held belief in psychology: that environments rule our behavior. Part of this idea was that almost any stimulus (whether a taste, sight, or sound) could serve equally well as a conditioned stimulus. Garcia and Koelling’s work put that idea to the test and proved it wrong. They noticed that rats would avoid a taste—

Humans, too, seem biologically prepared to learn some things rather than others. If you become violently ill four hours after eating a tainted hamburger, you will probably develop an aversion to the taste of hamburger. But you usually won’t avoid the sight of the associated restaurant, its plates, the people you were with, or the music you heard there.

Though Garcia and Koelling’s taste-

Such research supports Darwin’s principle that natural selection favors traits that aid survival. Our ancestors who readily learned taste aversions were unlikely to eat the same toxic food again and were more likely to survive and leave descendants. Nausea, like anxiety, pain, and other bad feelings, serves a good purpose. Like a car’s low-

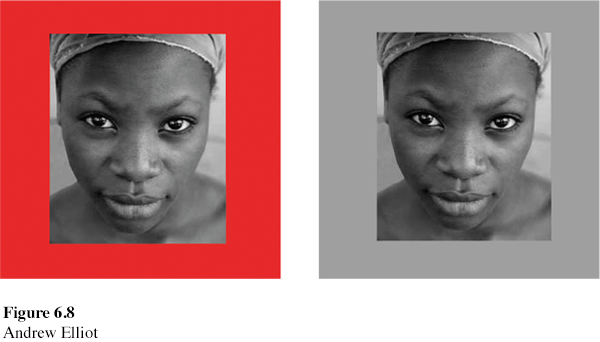

This tendency to learn behaviors favored by natural selection may help explain why we humans seem naturally disposed to learn associations between the color red and sexuality. Female primates display red when nearing ovulation. In human females, enhanced blood flow during sexual excitation may produce a red blush. Does the frequent pairing of red and sex—

Retrieve + Remember

Question 6.14

•How did Garcia and Koelling’s taste-

ANSWER: Garcia and Koelling demonstrated that rats may learn an aversion to tastes, on which their survival depends, but not to sights or sounds.

Limits on Operant Conditioning

As with classical conditioning, nature sets limits on each species’ capacity for operant conditioning. Science fiction writer Robert Heinlein (1907–

We most easily learn and retain behaviors that reflect our biological predispositions. Thus, using food as a reinforcer, you could easily condition a hamster to dig or to rear up, because these are among the animal’s natural food-

Cognitive Influences on Conditioning

LOQ 6-

Cognition and Classical Conditioning

behaviorism the view that psychology (1) should be an objective science that (2) studies behavior without reference to mental processes. Most research psychologists today agree with (1) but not with (2).

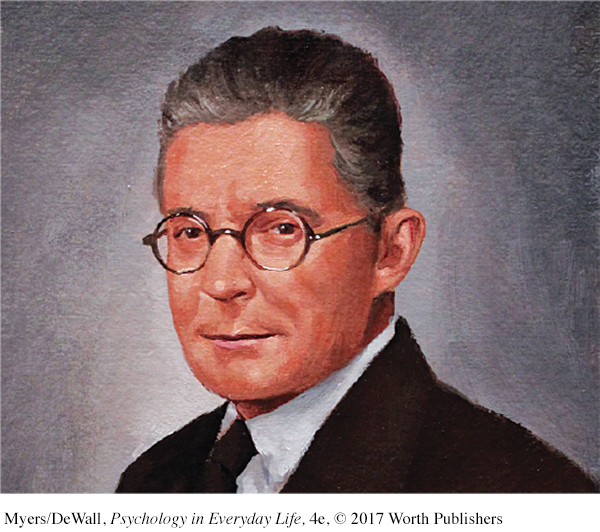

John B. Watson, the “Little Albert” researcher, was one of many psychologists who built on Ivan Pavlov’s work. Pavlov and Watson shared many beliefs. They avoided “mentalistic” concepts (such as consciousness) that referred to inner thoughts, feelings, and motives (Watson, 1913). They also maintained that the basic laws of learning are the same for all animals—

Later research has shown that Pavlov’s and Watson’s views of learning underestimated two important sets of influences. The first, as we have seen, is the way that biological predispositions limit our learning. The second is the effect of our cognitive processes—

The early behaviorists believed that rats’ and dogs’ learned behaviors were mindless mechanisms, so there was no need to consider cognition. But experiments have shown that animals can learn the predictability of an event (Rescorla & Wagner, 1972). If a shock always is preceded by a tone, and then may also be preceded by a light that accompanies the tone, a rat will react with fear to the tone but not to the light. Although the light is always followed by the shock, it adds no new information; the tone is a better predictor. It’s as if the animal learns an expectancy, an awareness of how likely it is that the US will occur.

Cognition matters in humans, too. For example, people being treated for alcohol use disorder may be given alcohol spiked with a nauseating drug. However, their awareness that the drug, not the alcohol, causes the nausea tends to weaken the association between drinking alcohol and feeling sick, making the treatment less effective. In classical conditioning, it is—

Cognition and Operant Conditioning

B. F. Skinner acknowledged the biological underpinnings of behavior and the existence of private thought processes. Nevertheless, many psychologists criticized him for discounting cognition’s importance.

A mere eight days before dying of leukemia in 1990, Skinner stood before those of us attending the American Psychological Association convention. In this final address, he again rejected the growing belief that presumed cognitive processes have a necessary place in the science of psychology and even in our understanding of conditioning. For Skinner, thoughts and emotions were behaviors that follow the same laws as other behaviors.

cognitive map a mental image of the layout of one’s environment.

latent learning learning that is not apparent until there is an incentive to demonstrate it.

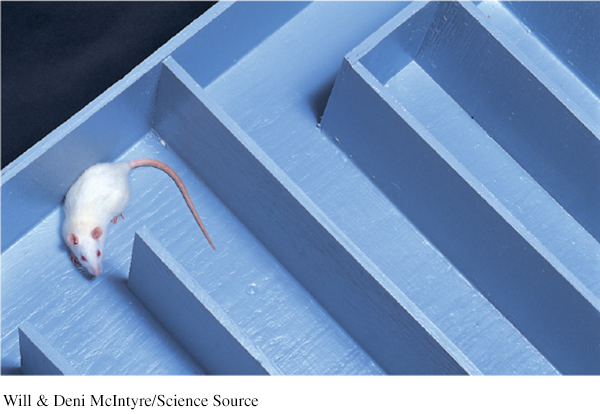

Nevertheless, the evidence of cognitive processes cannot be ignored. For example, rats exploring a maze, given no obvious rewards, seem to develop a cognitive map, a mental representation of the maze. In one study, when an experimenter placed food in the maze’s goal box, these roaming rats ran the maze as quickly as (and even faster than) other rats that had always been rewarded with food for reaching the goal. Like people sightseeing in a new town, the exploring rats seemingly experienced latent learning during their earlier tours. Their latent learning became evident only when they had some reason to demonstrate it.

intrinsic motivation a desire to perform a behavior well for its own sake.

The cognitive perspective shows the limits of rewards. Promising people a reward for a task they already enjoy can backfire. Excessive rewards can destroy intrinsic motivation—

extrinsic motivation a desire to perform a behavior to gain a reward or avoid punishment.

To sense the difference between intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation (behaving in certain ways to gain external rewards or to avoid threatened punishment), think about your experience in this course. Are you feeling pressured to finish this reading before a deadline? Worried about your grade? Eager for the credits that will count toward graduation? If Yes, then you are extrinsically motivated (as, to some extent, almost all students must be). Are you also finding the material interesting? Does learning it make you feel more competent? If there were no grade at stake, might you be curious enough to want to learn the material for its own sake? If Yes, intrinsic motivation also fuels your efforts. People who focus on their work’s meaning and significance not only do better work, but ultimately earn more extrinsic rewards (Wrzesniewski et al., 2014).

Nevertheless, extrinsic rewards that signal a job well done—

To sum up, TABLE 6.5 compares the biological and cognitive influences on classical and operant conditioning.

| Classical Conditioning | Operant Conditioning | |

|---|---|---|

| Biological influences | Biological tendencies limit the types of stimuli and responses that can easily be associated. Involuntary, automatic. | Animals most easily learn behaviors similar to their natural behaviors; associations that are not naturally adaptive are not easily learned. |

| Cognitive influences | Thoughts, perceptions, and expectations can weaken the association between the CS and the US. | Animals may develop an expectation that a response will be reinforced or punished; latent learning may occur without reinforcement. |

Retrieve + Remember

Question 6.15

•Latent learning is an example of what important idea?

ANSWER: The success of operant conditioning is affected not just by environmental cues, but also by cognitive factors.