7.2 Building Memories: Encoding

Our Two-

LOQ 7-

As we have seen throughout this text, our mind operates on two tracks. This theme appears again in the way we process memories:

implicit memory retention of learned skills, or classically conditioned associations, without conscious awareness. (Also called nondeclarative memory.)

automatic processing unconscious encoding of everyday information, such as space, time, and frequency, and of well-

On one track, information skips the Atkinson-

Shiffrin stages and barges directly into storage, without our awareness. These implicit memories (also called nondeclarative memories) form without our conscious effort. Implicit memories, formed through automatic processing, bypass the conscious encoding track. explicit memory retention of facts and personal events you can consciously retrieve. (Also called declarative memory.)

effortful processing encoding that requires attention and conscious effort.

On the second track, we process our explicit memories of the facts and experiences we can consciously know and declare. (Explicit memories are also called declarative memories.) We encode explicit memories through conscious, effortful processing. The Atkinson-

Shiffrin model helps us understand how this memory track operates.

Our two-

Automatic Processing and Implicit Memories

LOQ 7-

Your implicit memories include automatic skills (such as how to ride a bike) and classically conditioned associations. If attacked by a dog in childhood, years later you may, without recalling the conditioned association, automatically tense up as a dog approaches.

Without conscious effort, you also automatically process information about

space. While studying, you often encode the place on a page where certain material appears. Later, when you want to retrieve the information, you may visualize its location on the page.

Page 198time. While you are going about your day, your brain is working behind the scenes, jotting down the sequence of your day’s events. Later, if you realize you’ve left your coat somewhere, you can call up that sequence and retrace your steps.

frequency. Your behind-

the- scenes mind also keeps track of how often things have happened, thus enabling you to realize, “This is the third time I’ve run into her today!”

Parallel processing the processing of many aspects of a problem at the same time; the brain’s natural mode of information processing for many functions.

Your two-

Effortful Processing and Explicit Memories

Automatic processing happens effortlessly. When you see words in your native language, you can’t help but register their meaning. Learning to read was not automatic. You at first worked hard to pick out letters and connect them to certain sounds. But with experience and practice, your reading became automatic. Imagine now learning to read sentences in reverse:

.citamotua emoceb nac gnissecorp luftroffE

At first, this requires effort, but with practice it becomes more automatic. We develop many skills in this way: driving, texting, and speaking a new language. With practice, these tasks become automatic.

Sensory Memory

LOQ 7-

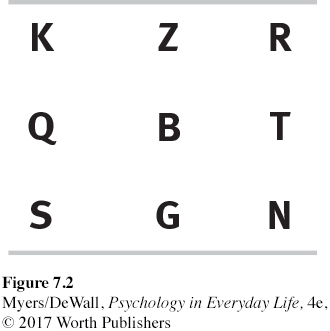

Sensory memory (recall FIGURE 7.1) is the first stage in forming explicit memories. A memory-

Was it because they had too little time to see them? No—the researcher demonstrated that people actually had seen, and could recall, all the letters, but only briefly (Sperling, 1960). He sounded a tone immediately after flashing the nine letters. A high tone directed people to report the top row of letters; a medium tone, the middle row; a low tone, the bottom row. With these cues, they rarely missed a letter, showing that all nine were briefly available for recall.

This fleeting sensory memory of the flashed letters was an iconic memory. For a few tenths of a second, our eyes retain a picture-

Short-Term Memory Capacity

LOQ 7-

Recall that short-

Memory researcher George Miller (1956) proposed that we can store about seven bits of information (give or take two) in this middle stage. Miller’s Magical Number Seven is psychology’s contribution to the list of magical sevens—

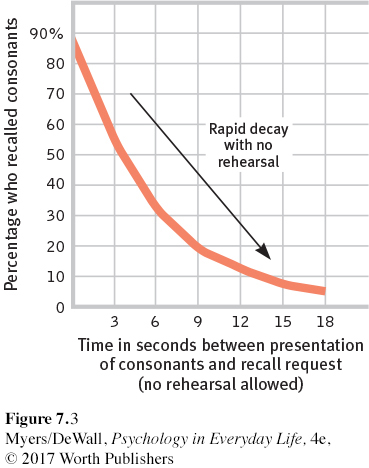

Other researchers have confirmed that we can, if nothing distracts us, recall about seven digits, or about six letters or five words (Baddeley et al., 1975). How quickly do our short-

Working-

For a review of memory stages and a test of your own short-

For a review of memory stages and a test of your own short-

Effortful Processing Strategies

LOQ 7-

Let’s recap. To form an explicit memory (a lasting memory of a fact or an experience) it helps to focus our attention and make a conscious effort to remember. But our working-

We can boost our ability to form new explicit memories by using specific effortful processing strategies, such as chunking and mnemonics.

Chunking organizing items into familiar, manageable units; often occurs automatically.

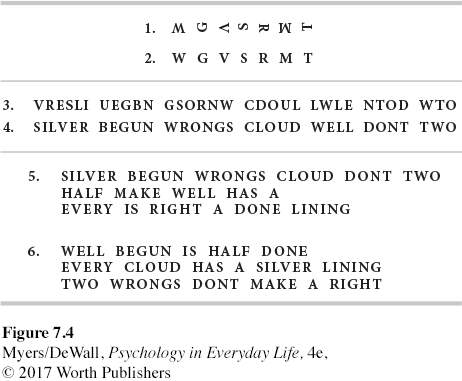

Chunking: When we chunk information, we organize items into familiar, manageable units. Glance for a few seconds at row 1 of FIGURE 7.4, then look away and try to draw those forms. Impossible, yes? But you can easily reproduce row 2, which is just as complex. And row 4 is probably much easier to remember than row 3, although both contain the same letters. As you can see, chunking information helps us to recall it more easily.

Chunking usually occurs so naturally that we take it for granted. Try remembering 43 individual numbers and letters. It would be impossible, unless chunked into, say, seven meaningful chunks—

such as “Try remembering 43 individual numbers and letters!”

mnemonics [nih-

MON- iks] memory aids, especially techniques that use vivid imagery and organizational devices. Mnemonics: In ancient Greece, scholars and public speakers needed memory aids to help them encode long passages and speeches. They developed mnemonics, which often rely on vivid imagery. We are particularly good at remembering mental pictures. Concrete words that create these mental images are easier to remember than other words that describe abstract ideas. (When we quiz you later, which three of these words—bicycle, void, cigarette, inherent, fire, process—

will you most likely recall?) Do you still recall the rock- throwing rioter sentence mentioned at the beginning of this chapter? If so, it is probably not only because of the meaning you encoded but also because the sentence painted a mental image.

Memory whizzes understand the power of such systems. Star performers in the World Memory Championships do not usually have exceptional intelligence. Rather, they are superior at using mnemonic strategies (Maguire et al., 2003). Frustrated by his ordinary memory, science writer Joshua Foer wanted to see how much he could improve it. After a year of intense practice, he won the U.S. Memory Championship by memorizing a pack of 52 playing cards in under two minutes. How did Foer do it? He added vivid new details to memories of a familiar place—

* * *

Effortful processing requires closer attention and effort, and chunking and mnemonics help us form meaningful and accessible memories. But memory researchers have also discovered other important influences on how we capture information and hold it in memory.

Retrieve + Remember

Question 7.3

•What is the difference between automatic and effortful processing, and what are some examples of each?

ANSWER: Automatic processing occurs unconsciously (automatically) for such things as the sequence and frequency of a day’s events, and reading and understanding words in our own language(s). Effortful processing requires us to focus attention and make an effort, as when we work hard to learn new material in class, or new lines for a play.

Question 7.4

•At which of Atkinson-

ANSWER: sensory memory

Spaced Study and Self-Assessment

LOQ 7-

spacing effect the tendency for distributed study or practice to yield better long-

We retain information better when our encoding is spread over time. Psychologists call this the spacing effect, and more than 300 experiments have confirmed that distributed practice produces better long-

testing effect enhanced memory after retrieving, rather than simply rereading, information. Also sometimes referred to as the retrieval practice effect or test-

One effective way to distribute practice is repeated self-

Here is another sentence we will ask you about later: The fish attacked the swimmer.

The point to remember: Spaced study and self-

Making New Information Meaningful

Spaced practice helps, but if new information is not meaningful or related to your experience, you will have trouble processing it. Imagine being asked to remember this passage (Bransford & Johnson, 1972):

The procedure is actually quite simple. First you arrange things into different groups. Of course, one pile may be sufficient depending on how much there is to do. . . . After the procedure is completed one arranges the materials into different groups again. Then they can be put into their appropriate places. Eventually they will be used once more and the whole cycle will then have to be repeated. However, that is part of life.

When some students heard the paragraph you just read, without a meaningful context, they remembered little of it. Others were told the paragraph described doing laundry (something meaningful to them). They remembered much more of it—

Can you repeat the sentence about the angry rioter (from this chapter’s opening section)?

Was the sentence “The angry rioter threw the rock through the window” or “The angry rioter threw the rock at the window”? If the first looks more correct, you—

We can avoid some encoding errors by translating what we see and hear into personally meaningful terms. From his experiments on himself, Hermann Ebbinghaus estimated that, compared with learning nonsense material, learning meaningful material required one-

The point to remember: You can profit from taking time to find personal meaning in what you are studying.

Retrieve + Remember

Question 7.5

•Which strategies are better for long-

ANSWER: Although cramming and rereading may lead to short-