7.4 Retrieval: Getting Information Out

Remembering an event requires more than getting information into our brain and storing it there. To use that information, we must retrieve it. How do psychologists test whether learning has been retained over time? What triggers retrieval?

Measuring Retention

LOQ 7-

Memory is learning that persists over time. Three types of evidence indicate whether something has been learned and retained:

Recall memory demonstrated by retrieving information learned earlier, as on a fill-

Recall—retrieving information out of storage and into your conscious awareness. Example: a fill-

in- the- blank question. recognition memory demonstrated by identifying items previously learned, as on a multiple-

choice test. Recognition—identifying items you previously learned. Example: a multiple-

choice question. relearning memory demonstrated by time saved when learning material a second time.

Relearning—learning something more quickly when you learn it a second or later time. Example: Reviewing the first weeks of course work to prepare for your final exam, you will relearn the material more easily than you did originally.

Long after you cannot recall most of your high school classmates, you may still be able to recognize their yearbook pictures and spot their names in a list of names. One research team found that people who had graduated 25 years earlier could not recall many of their old classmates, but they could recognize 90 percent of their pictures and names (Bahrick et al., 1975).

Our recognition memory is quick and vast. “Is your friend wearing a new or old outfit?” Old. “Is this 5-

Our response speed when recalling or recognizing information indicates memory strength, as does our speed at relearning. Memory explorer Ebbinghaus showed this long ago by studying his own learning and memory.

Put yourself in Ebbinghaus’ shoes. How could you produce new items to learn? Ebbinghaus’ answer was to form a list of all possible nonsense syllables by sandwiching a vowel between two consonants. Then, for a particular experiment, he would randomly select a sample of the syllables, practice them, and test himself. To get a feel for his experiments, rapidly read aloud the following list, repeating it eight times (from Baddeley, 1982). Then, without looking, try to recall the items:

JIH, BAZ, FUB, YOX, SUJ, XIR, DAX, LEQ, VUM, PID, KEL, WAV, TUV, ZOF, GEK, HIW.

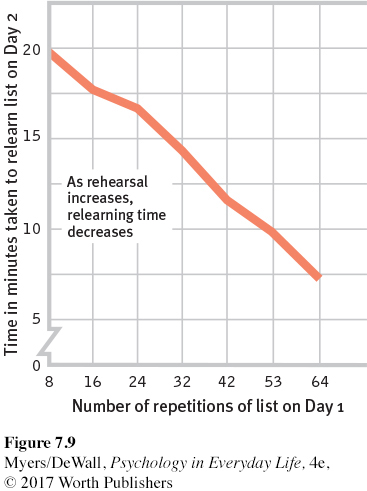

The day after learning such a list, Ebbinghaus recalled only a few of the syllables. But were they entirely forgotten? No. The more often he practiced the list aloud on Day 1, the fewer times he would have to practice it to relearn it on Day 2 (FIGURE 7.9).

The point to remember: Tests of recognition and of time spent relearning demonstrate that we remember more than we can recall.

Retrieve + Remember

Question 7.10

•Multiple-

recall.

recognition.

learning.

sensory memory.

ANSWER: b

Question 7.11

•Fill-

ANSWER: recall

Question 7.12

•If you want to be sure to remember what you’re learning for an upcoming test, would it be better to use recall or recognition to check your memory? Why?

ANSWER: It would be better to test your memory with recall (such as with short-

Retrieval Cues

LOQ 7-

Imagine a spider suspended in the middle of her web, held up by the many strands extending outward from her in all directions to different points. You could begin at any one of these anchor points and follow the attached strand to the spider.

retrieval cue any stimulus (event, feeling, place, and so on) linked to a specific memory.

Retrieving a memory is similar. Memories are held in storage by a web of associations, each piece of information connected to many others. Suppose you encode into your memory the name of the person sitting next to you in class. With that name, you will also encode other bits of information, such as your surroundings, mood, seating position, and so on. These bits serve as retrieval cues, anchor points for pathways you can follow to access your classmate’s name when you need to recall it later. The more retrieval cues you’ve encoded, the better your chances of finding a path to the memory suspended in this web of information.

The best retrieval cues come from associations you form at the time you encode a memory—

For an 8-

For an 8-

I knew I had been somewhere, and had done particular things with certain people, but where? I could not put the conversations . . . into a context. There was no background, no features against which to identify the place. Normally, the memories of people you have spoken to during the day are stored in frames which include the background.

Priming

priming the activation, often unconsciously, of particular associations in memory.

Often associations are activated without your awareness. Seeing or hearing the word rabbit can activate associations with hare, even though you may not recall having seen or heard rabbit (FIGURE 7.10). Although this process, called priming, happens without your conscious awareness, it can influence your attitudes and your behavior.

Want to impress your friends with your new knowledge? Ask them three rapid-

What color is snow?

What color are clouds?

What do cows drink?

If they answer milk to the third question, you have demonstrated priming.

Context-Dependent Memory

Have you noticed? Putting yourself back in the context where you experienced something can prime your memory retrieval. Remembering, in many ways, is an action that depends on our environment (Palmer, 1989). Childhood memories may surface when you visit your childhood home. In one study, scuba divers listened to a list of words in two different settings, either 10 feet underwater or sitting on the beach (Godden & Baddeley, 1975). Later, the divers recalled more words when they were tested in the same place.

By contrast, experiencing something outside the usual setting can be confusing. Have you ever run into a former teacher in an unusual place, such as at the store? Maybe you recognized the person but struggled to figure out who it was and how you were acquainted. Our memories are context-

State-Dependent Memory

State-

Moods also influence what we remember (Gaddy & Ingram, 2014). Being happy primes sweet memories. Being angry or depressed primes sour ones. Say you have a terrible evening. Your date canceled, you lost your phone, and now a new red sweatshirt somehow made its way into your white laundry batch. Your bad mood may trigger other unhappy memories. If a friend or family member walks in at this point, your mind may fill with bad memories of that person.

mood-

This tendency to recall events that fit our mood is called mood-

Knowing this mood-

Mood effects on retrieval help explain why our moods persist. When happy, we recall happy events and see the world as a happy place, which prolongs our good mood. When depressed, we recall sad events, which darkens our view of current events. For those predisposed to depression, this process can help maintain a vicious, dark cycle. Moods magnify.

Serial Position Effect

serial position effect our tendency to recall best the last and first items in a list.

Another memory-

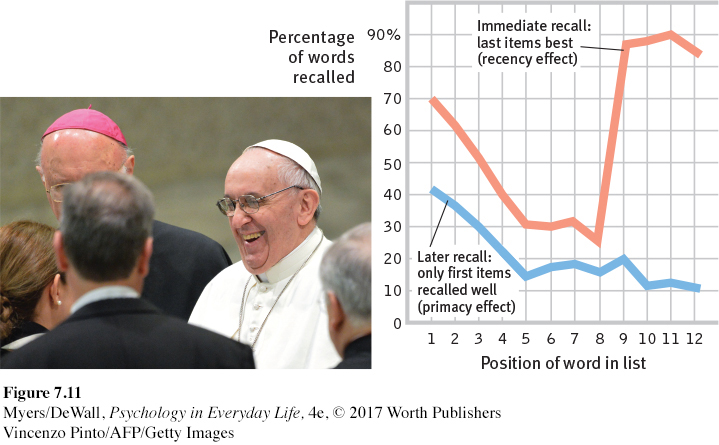

Don’t count on it. Because you have spent more time rehearsing the earlier names than the later ones, those are the names you’ll probably recall more easily the next day. In experiments, when people viewed a list of items (words, names, dates, even experienced odors) and immediately tried to recall them in any order, they fell prey to the serial position effect (Reed, 2000). They briefly recalled the last items especially quickly and well (a recency effect), perhaps because those last items were still in working memory. But after a delay, when their attention was elsewhere, their recall was best for the first items (a primacy effect; see FIGURE 7.11).

Retrieve + Remember

Question 7.13

•What is priming?

ANSWER: Priming is the activation (often without our awareness) of associations.

Question 7.14

•When we are tested immediately after viewing a list of words, we tend to recall the first and last items best. This is known as the _______ _______ effect.

ANSWER: serial position