Preface

PSYCHOLOGY IS FASCINATING, and so relevant to our everyday lives. Psychology’s insights enable us to be better students, more tuned-

For those of you familiar with other Myers/DeWall introductory psychology texts, you may be surprised at how different this text is. We have created this very brief, uniquely student-

What’s New in the Fourth Edition?

In addition to thorough updating of every chapter, with new infographic “Thinking Critically About” features, this fourth edition offers exciting new activities in the teaching package.

Hundreds of New Research Citations

Our ongoing scrutiny of dozens of scientific periodicals and science news sources, enhanced by commissioned reviews and countless e-

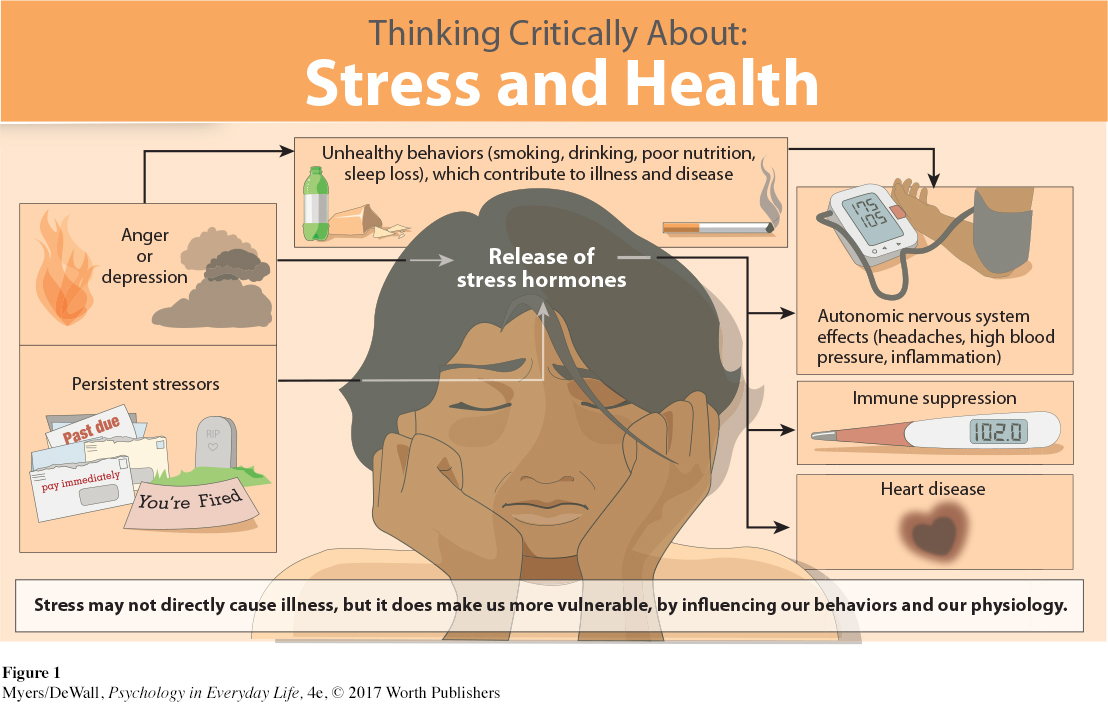

“Thinking Critically About” Infographic features

We worked with an artist to create infographic critical thinking features. (In many cases, these new infographics replace a more static boxed essay in the previous edition.) Several dozen instructors reviewed this feature, often sharing it with their students, and they were unanimously supportive. Students seem to enjoy engaging this visual tool for thinking critically about key psychological concepts (parenting styles, gender bias, group polarization, introversion, lifestyle changes, and more). A picture can indeed be worth a thousand words! (See FIGURE 1 for an example.)

“Assess Your Strengths” Activities for LaunchPad

With the significantly revised Assess Your Strengths activities, students apply what they are learning from the text to their own lives and experiences by considering key “strengths.” For each of these activities, we [DM and ND] start by offering a personalized video introduction, explaining how that strength ties in to the content of the chapter. Next, we ask students to assess themselves on the strength (critical thinking, quality of sleep, self-

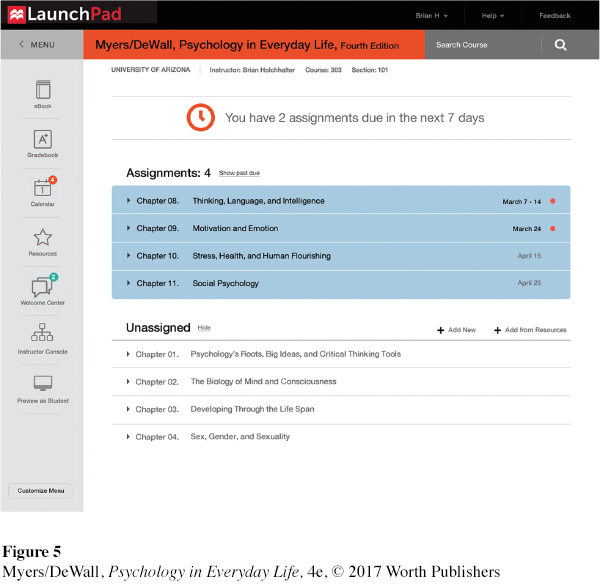

These activities reside in LaunchPad, an online resource designed to help achieve better course results. LaunchPad for Psychology in Everyday Life, Fourth Edition, also includes LearningCurve formative assessment and the “Immersive Learning: How Would You Know?” activities described next. For details, see p. xxii and LaunchPadWorks.com. For this new edition, you will see that we’ve offered callouts from the text pages to especially pertinent, helpful resources elsewhere in LaunchPad. (See FIGURE 2 for a sample.)

To review the classic conformity studies and experience a simulated experiment, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Everybody’s Doing It!

To review the classic conformity studies and experience a simulated experiment, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Everybody’s Doing It!

FIGURE 2 Sample LaunchPad callout from Chapter 1

“Immersive Learning: How Would You Know?” Research Activities

We [ND and DM] created these online activities to engage students in the scientific process, showing them how psychological research begins with a question, and how key decision points can alter the meaning and value of a psychological study. In a fun, interactive environment, students learn about important aspects of research design and interpretation, and develop scientific literacy and critical thinking skills in the process. I [ND] have enjoyed taking the lead on this project and sharing my research experience and enthusiasm with students. Topics include: “How Would You Know If a Cup of Coffee Can Warm Up Relationships?”; “How Would You Know If People Can Learn to Reduce Anxiety?”; and “How Would You Know If Schizophrenia Is Inherited?”

What Continues in the Fourth Edition?

Eight Guiding Principles

Despite all the exciting changes, this new edition retains its predecessors’ voice, as well as much of the content and organization. It also retains the goals—

Facilitating the Learning Experience

1. To teach critical thinking By presenting research as intellectual detective work, we illustrate an inquiring, analytical mind-

2. To integrate principles and applications Throughout—

3. To reinforce learning at every step Everyday examples and rhetorical questions encourage students to process the material actively. Concepts presented earlier are frequently applied, and reinforced, in later chapters. For instance, in Chapter 1, students learn that much of our information processing occurs outside of our conscious awareness. Ensuing chapters drive home this concept. Numbered Learning Objective Questions, Retrieve + Remember self-

Demonstrating the Science of Psychology

4. To exemplify the process of inquiry We strive to show students not just the outcome of research, but how the research process works. Throughout, the book tries to excite the reader’s curiosity. It invites readers to imagine themselves as participants in classic experiments. Several chapters introduce research stories as mysteries that progressively unravel as one clue after another falls into place. Our new “Immersive Learning: How Would You Know?” activities in LaunchPad encourage students to think about research questions and how they may be studied effectively.

5. To be as up-

6. To put facts in the service of concepts Our intention is not to fill students’ intellectual file drawers with facts, but to reveal psychology’s major concepts—

Promoting Big Ideas and Broadened Horizons

7. To enhance comprehension by providing continuity Many chapters have a significant issue or theme that links subtopics, forming a thread that ties the chapter together. The Learning chapter conveys the idea that bold thinkers can serve as intellectual pioneers. The Thinking, Language, and Intelligence chapter raises the issue of human rationality and irrationality. The Psychological Disorders chapter conveys empathy for, and understanding of, troubled lives. Other threads, such as cognitive neuroscience, dual processing, and cultural and gender diversity, weave throughout the whole book, and students hear a consistent voice.

8. To convey respect for human unity and diversity Throughout the book, readers will see evidence of our human kinship in our shared biological heritage—

The Writing

As with the third edition, we’ve written this book to be optimally accessible. The vocabulary is sensitive to students’ widely varying reading levels and backgrounds. (A Spanish language Glosario at the back of the book offers additional assistance for ESL Spanish speakers.) And this book is briefer than many texts on the market, making it easier to fit into one-

No Assumptions

Even more than in other Myers/DeWall texts, we have written Psychology in Everyday Life with the diversity of student readers in mind.

Gender: Extensive coverage of gender roles and gender identity and the increasing diversity of choices men and women can make.

Culture: No assumptions about readers’ cultural backgrounds or experiences.

Economics: No references to backyards, summer camp, vacations.

Education: No assumptions about past or current learning environments; writing is accessible to all.

Physical Abilities: No assumptions about full vision, hearing, movement.

Life Experiences: Examples are included from urban, suburban, and rural/outdoor settings.

Family Status: Examples and ideas are made relevant for all students, whether they have children or are still living at home, are married or cohabiting or single; no assumptions about sexual orientation.

Four Big Ideas

In the general psychology course, it can be a struggle to weave psychology’s disparate parts into a cohesive whole for students, and for students to make sense of all the pieces. In Psychology in Everyday Life, we have introduced four of psychology’s big ideas as one possible way to make connections among all the concepts. These ideas are presented in Chapter 1 and gently integrated throughout the text.

1. Critical Thinking Is Smart Thinking

We love to write in a way that gets students thinking and keeps them active as they read. Students will see how the science of psychology can help them evaluate competing ideas and highly publicized claims—

In Psychology in Everyday Life, students have many opportunities to learn or practice critical thinking skills. (See TABLE 1 for a complete list of this text’s coverage of critical thinking topics.)

|

Critical thinking coverage can be found on the following pages: |

|||

|

A scientific model for studying psychology, pp. 174– Are intelligence tests biased?, pp. 251– Are personality tests able to predict behavior?, p. 362 Attachment style, development of, pp. 83– Attention- Can memories of childhood sexual abuse be repressed and then recovered?, p. 214 Causation and the violence- Classifying psychological disorders, pp. 379– Confirmation bias, p. 223 Continuity vs. stage theories of development, pp. 68– Correlation and causation, pp. 16– Critical thinking defined, p. 8 Critiquing the evolutionary perspective on sexuality, pp. 126– Discovery of hypothalamus reward centers, p. 42 Do lie detectors lie?, p. 276 Do other species have language?, pp. 236– Do other species share our cognitive abilities?, pp. 230– Do video games teach, or release, violence?, p. 334 Does meditation enhance health?, pp. 300– |

Effectiveness of alternative psychotherapies, p. 428 Emotion and the brain, pp. 37, 39– Emotional intelligence, p. 240 Evolutionary science and human origins, pp. 128– Extrasensory perception, pp. 162– Fear of flying vs. probabilities, p. 225 Freud’s contributions, pp. 355– Gender bias in the workplace, p. 110 Genetic and environmental influences on schizophrenia, pp. 403– Group differences in intelligence, pp. 248– Hindsight bias, pp. 11– How do nature and nurture shape prenatal development?, pp. 70– How do twin and adoption studies help us understand the effects of nature and nurture?, pp. 74– How does the brain process language?, pp. 234– How much is gender socially constructed vs. biologically influenced?, pp. 111– How valid is the Rorschach inkblot test?, p. 355 Human curiosity, pp. 2, 3 Humanistic perspective, evaluating, p. 359 Hypnosis: dissociation or social influence?, pp. 157– |

Importance of checking fears against facts, p. 225 Interaction of nature and nurture in overall development, p. 68 Is dissociative identity disorder a real disorder?, pp. 407– Is psychotherapy effective?, pp. 426– Is repression a myth?, p. 356 Limits of case studies, naturalistic observation, and surveys, p. 16 Limits of intuition, pp. 10– Nature, nurture, and perceptual ability, pp. 151– Overconfidence, pp. 12, 226 Parenting styles, p. 87 Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), pp. 382– Powers and limits of parental involvement on development, pp. 93– Powers and perils of intuition, pp. 227– Problem- Psychic phenomena, pp. 3, 162– Psychology: a discipline for critical thought, pp. 11, 14, 16 |

Religious involvement and longevity, pp. 301– Scientific attitude, p. 3 Scientific method, pp. 12– Sexual desire and ovulation, p. 116 Similarities and differences in social power between men and women, pp. 109, 110 Stress and cancer, p. 290 Stress and health, p. 292 Subliminal sensation and persuasion, p. 136 Technology and “big data” observations, p. 15 The divided brain, pp. 48– Therapeutic lifestyle change, p. 431 The stigma of introversion, p. 361 The Internet as social amplifier, p. 326 Using more than 10 percent of our brain, p. 46 Using psychology to debunk popular beliefs, p. 8 Values and psychology, pp. 21– What does selective attention teach us about consciousness?, pp. 51– What factors influence sexual orientation?, pp. 121– What is the connection between the brain and the mind?, p. 38 Wording effects, pp. 15– |

Chapter 1 takes a unique, critical thinking approach to introducing students to psychology’s research methods. Understanding the weak points of our everyday intuition and common sense helps students see the need for psychological science. Critical thinking is introduced as a key term in this chapter (page 8).

“Thinking Critically About . . .” infographic features are found in each chapter. This feature models for students a critical approach to some key issues in psychology. For example, see “Thinking Critically About: The Stigma of Introversion” (Chapter 12) or “Thinking Critically About: The Internet as Social Amplifier” (Chapter 11).

Detective-

style stories throughout the text get students thinking critically about psychology’s key research questions. In Chapter 8, for example, we present as a puzzle the history of discoveries about where and how language happens in the brain. We guide students through the puzzle, showing them how researchers put all the pieces together.- Page xviii

“Try this” and “think about it” style discussions and side notes keep students active in their study of each chapter. We often encourage students to imagine themselves as participants in experiments. In Chapter 11, for example, students take the perspective of participants in a Solomon Asch conformity experiment and, later, in one of Stanley Milgram’s obedience experiments. We’ve also asked students to join the fun by taking part in activities they can try along the way. Here are two examples: In Chapter 5, they try out a quick sensory adaptation activity. In Chapter 9, they test the effects of maintaining different facial expressions.

2. Behavior Is a Biopsychosocial Event

Students will learn that we can best understand human behavior if we view it from three levels—

|

Coverage of culture and multicultural experience can be found on the following pages: |

|||

|

Academic achievement, pp. 249– Achievement motivation, p. B- Adolescence, onset and end of, pp. 94– Aggression, pp. 332– Animal learning, p. 231 Animal research, views on, p. 22 Beauty ideals, p. 337 Biopsychosocial approach, pp. 7, 68, 111– Body image, p. 406 Child raising, pp. 86– Cognitive development of children, p. 82 Collectivism, p. 319 Crime and stress hormone levels, p. 408 Cultural values child raising and, pp. 86– morality and, p. 90 psychotherapy and, p. 429 Culture defined, p. 9 emotional expression and, pp. 278– intelligence test bias and, p. 251 the self and, pp. 369– Deindividuation, p. 324 Depression and suicide, p. 400 risk of, p. 397 Developmental similarities across cultures, p. 68 Discrimination, pp. 327– Dissociative identity disorder, p. 407 Division of labor, p. 114 Divorce rate, p. 99 Dysfunctional behavior diagnoses, pp. 376– Eating disorders, p. 378 Enemy perceptions, p. 342 |

Expressions of grief, p. 101 Family environment, p. 92 Family self, sense of, pp. 86– Father’s presence pregnancy and, p. 120 violence and, p. 333 Flow, pp. B- Foot- Framing, and organ donation, p. 227 Fundamental attribution error, p. 314 Gender roles, pp. 110, 113– Gender aggression and, pp. 108– communication and, p. 109 sex drive and, p. 116 General adaptation syndrome, p. 287 Groupthink, pp. 325– Happiness, pp. 303, 305, 306– HIV/AIDS, pp. 118, 290 Homosexuality, attitudes toward, p. 121 Identity formation, pp. 91– Individualism, pp. 314, 319, 324 ingroup bias, p. 329 moral development and, p. 90 Intelligence, p. 238 group differences in, pp. 248– test scores, p. 249 Intelligence testing, pp. 240– |

Interracial dating, p. 327 Job satisfaction, p. B- Just- Language development, p. 234 Leadership, p. B- Life cycle, p. 68 Marriage, pp. 338– Mating preferences, p. 126 Mental disorders and stress, p. 378 Mere exposure effect, p. 335 Migration, p. 267 Motivation, p. 260 Naturalistic observation, pp. 14– Need to belong, pp. 266– Obedience, p. 321 Obesity, p. 264 and sleep loss, p. 265 Optimism, p. 296 Ostracism, p. 267 Parent- Partner selection, p. 337 Peace, promoting, pp. 342– Personal control, p. 294 Personality traits, p. 360 Phobias, p. 382 Physical attractiveness, p. 337 Poverty, explanations of, p. 315 Power differences between men and women, pp. 109, 110 Prejudice, pp. 327– automatic, pp. 327– contact, cooperation, and, pp. 342– forming categories, p. 330 group polarization and, p. 325 racial, pp. 316, 327– subtle versus overt, pp. 327– unconscious, Supreme Court’s recognition of, p. 328 Prosocial behavior, pp. 188– Psychoactive drugs, pp. 393– Psychological disorders, pp. 376– treatment of, p. 429 |

Race- Racial similarities, pp. 249– Religious involvement and longevity, p. 301 Resilience, p. 438 Risk assessment, p. 224 Scapegoat theory, p. 329 Schizophrenia, pp. 403– Self- Self- Separation anxiety, p. 84 Serial position effect, p. 207 Sexual risk- Social clock variation, p. 100 Social influence, pp. 319, 321– Social loafing, p. 324 Social networking, p. 268 Social support, p. 302 Social trust, p. 86 Social- Stereotype threat, pp. 251– Stereotypes, pp. 327, 329 Substance use disorders, pp. 386– rates of, p. 386 Susto, p. 378 Taijin- Taste preference, p. 263 Terrorism, pp. 224, 225 Trauma, pp. 356, 426 Universal expressions, p. 8 Video game playing compulsive, p. 386 effects of, p. 334 Weight, p. 264 Well- |

|

Coverage of the psychology of women and men can be found on the following pages: |

||

|

Age and decreased fertility, p. 96 Aggression, pp. 108– testosterone and, p. 331 Alcohol use and sexual assault, p. 387 Alcohol use disorder, p. 387 Alcohol, women’s greater physical vulnerability, p. 387 Attraction, pp. 335– Beauty ideals, pp. 336– Bipolar disorder, p. 395 Body image, p. 406 Brain scans, and sex- Depression, pp. 396– among girls, p. 92 higher vulnerability of women, pp. 396– seasonal pattern, p. 394 Eating disorders, p. 108 Emotion, p. 277 ability to detect, p. 277 expressiveness, p. 277 identification of as masculine or feminine, p. 277 Empathy, p. 277 Father’s presence pregnancy rates and, p. 120 lower sexual activity and, p. 120 Freud’s views on gender identity development, p. 352 Gender, pp. 8– anxiety and, p. 396 biological influences on, pp. 111– changes in society’s thinking about, pp. 114, 128 social- workplace bias and, p. 110 |

Gender differences, pp. 8– rumination and, p. 399 evolutionary perspectives on, pp. 124– intelligence and, pp. 248– sexuality and, p. 125 Gender discrimination, p. 328 Gender identity, development of, pp. 114– in transgender individuals, p. 115 Gender roles, p. 114 Gender schema theory, p. 114 Gender similarities, pp. 108– Gender typing, p. 114 Generalized anxiety disorder, p. 381 HIV/AIDS, women’s vulnerability to, p. 118 Hormones and sexual behavior, pp. 116– Human sexuality, pp. 116– Leadership styles, p. 110 Learned helplessness, pp. 398– Love companionate, pp. 338– passionate, p. 338 Marriage, pp. 98– Motor development, infant massage and, p. 77 Mating preferences, pp. 125– Maturation, pp. 88– Menarche, p. 88 Menopause, p. 96 Pain, women’s greater sensitivity to, p. 156 Physical attractiveness, pp. 336– Posttraumatic stress disorder, p. 383 |

Puberty, pp. 88– early onset of, p. 88 Relationship equity, p. 339 Responses to stress, p. 288 Schizophrenia, p. 402 Sex, pp. 8, 116– Sex and gender, p. 108 Sex chromosomes, p. 111 Sex drive, gender differences, pp. 117– Sex hormones, pp. 111, 116 Sex- Sexual activity and aging, p. 97 Sexual activity, teen girls’ regret, p. 119 Sexual arousal, gender and gay- Sexual intercourse among teens, pp. 119– Sexual orientation, pp. 121– Sexual response cycle, p. 116 Sexual response, alcohol- Sexual scripts, p. 333 Sexuality, natural selection and, pp. 125– Sexualization of girls, p. 120 Sexually explicit media, p. 333 Sexually transmitted infections, p. 118 Similarities and differences between men and women, pp. 108– Social clock, p. 100 Social connectedness, pp. 109– Social power, p. 109 Spirituality and longevity, p. 301 Substance use disorder and the brain, p. 387 Teen pregnancy, pp. 119– Violent crime, p. 108 Vulnerability to psychological disorders, p. 108 Women in psychology, pp. 2, 4 |

3. We Operate With a Two-Track Mind (Dual Processing)

Today’s psychological science explores our dual-

4. Psychology Explores Human Strengths as Well as Challenges

Students will learn about the many troublesome behaviors and emotions psychologists study, as well as the ways psychologists work with those who need help. Yet students will also learn about the beneficial emotions and traits that psychologists study, and the ways psychologists (some as part of the new positive psychology movement—

| Coverage of positive psychology topics can be found in the following chapters: | |

| Topic | Chapter |

|---|---|

| Altruism/compassion | 3, 8, 11, 12, 14 |

| Coping | 10 |

| Courage | 11 |

| Creativity | 6, 8, 11, 12 |

| Emotional intelligence | 9, 11 |

| Empathy | 3, 6, 10, 11, 14 |

| Flow | 10, App B |

| Gratitude | 9, 10 |

| Happiness/life satisfaction | 3, 9, 10, 11 |

| Humility | 11 |

| Humor | 10 |

| Justice | 3, 11 |

| Leadership | 11, 12, App B |

| Love | 3, 4, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 |

| Morality | 3 |

| Optimism | 10, 12 |

| Personal control | 10 |

| Resilience | 3, 10, 11, 14 |

| Self- |

3, 8, 9, 12, App B |

| Self- |

10 |

| Self- |

10, 12 |

| Self- |

3, 4, 9, 11, 12 |

| Spirituality | 3, 4, 10 |

| Toughness (grit) | 8, App B |

| Wisdom | 3, 8, 12 |

Everyday Life Applications

Throughout this text, as its title suggests, we relate the findings of psychology’s research to the real world. This edition includes:

chapter-

ending “In Your Everyday Life” questions, helping students make the concepts more meaningful (and memorable). “Assess Your Strengths” personal self-

assessments in LaunchPad, allowing students to actively apply key principles to their own experiences. fun notes and quotes in small boxes throughout the text, applying psychology’s findings to sports, literature, world religions, music, and more.

an emphasis throughout the text on critical thinking in everyday life, including the “Statistical Reasoning in Everyday Life” appendix, helping students to become more informed consumers and everyday thinkers.

Scattered throughout this book, students will find interesting and informative review notes and quotes from researchers and others that will encourage them to be active learners and to apply their new knowledge to everyday life.

added emphasis on clinical applications. Psychology in Everyday Life offers a great sensitivity to clinical issues throughout the text. For example, Chapter 13, Psychological Disorders, includes lengthy coverage of substance-

related disorders, with guidelines for determining substance use disorder. See TABLE 5 for a listing of coverage of clinical psychology concepts and issues throughout the text.

See inside the front and back covers (or at the beginning of the e-

|

Coverage of clinical psychology can be found on the following pages: |

|||

|

Abused children, risk of psychological disorder among, p. 174 Alcohol use and aggression, p. 332 Alzheimer’s disease, pp. 33, 195, 264 Anxiety disorders, pp. 380– Autism spectrum disorder, pp. 80– Aversive conditioning, pp. 421– Behavior modification, p. 422 Behavior therapies, pp. 419– Big Five, use in understanding personality disorders, p. 362 Bipolar disorder, pp. 395– Brain damage and memory loss, p. 208 Brain scans, p. 38 Brain stimulation therapies, pp. 434– Childhood trauma, effect on mental health, p. 86 Client- Client- Clinical psychologists, pp. 5– Cognitive therapies, pp. 422– eating disorders and, pp. 423– Culture and values in psychotherapy, p. 429 |

Depression: adolescence and, p. 92 heart disease and, pp. 291– homosexuality and, p. 121 mood- outlook and, p. 399 self- social exclusion and, p. 93 unexpected loss and, p. 101 Dissociative and personality disorders, pp. 406– Dissociative identity disorder, therapist’s role, pp. 407– Drug therapies, pp. 18– DSM- Eating disorders, pp. 405– Emotional intelligence, p. 240 Evidence- Exercise, therapeutic effects of, pp. 298– Exposure therapies, pp. 420– Generalized anxiety disorder, p. 381 Grief therapy, p. 101 Group and family therapies, p. 425 Historical treatment of mental illness, p. 416 Hospitals, clinical psychologists and, p. 416 |

Humanistic therapies, pp. 418– Hypnosis and pain relief, pp. 157– Intelligence scales and stroke rehabilitation, p. 242 Lifestyle change, therapeutic effects of, p. 431 Loss of a child, psychiatric hospitalization and, p. 101 Major depressive disorder, pp. 394– Medical model of mental disorders, p. 378 Neurotransmitter imbalances and related disorders, pp. 33– Nurturing strengths, pp. 358– Obsessive- Operant conditioning, p. 422 Ostracism, pp. 267– Panic disorder, pp. 381– Person- Personality inventories, pp. 361– Personality testing, pp. 361– Phobias, p. 382 Physical and psychological treatment of pain, pp. 155– Posttraumatic stress disorder, pp. 382– Psychiatric labels and bias, pp. 379– Psychoactive drugs, types of, pp. 385– |

Psychoanalysis, pp. 416– Psychodynamic theory, pp. 350– Psychodynamic therapy, pp. 417– Psychological disorders, pp. 375– are those with disorders dangerous?, pp. 409– classification of, pp. 379– gender differences in, p. 108 preventing, and building resilience, pp. 436– Psychotherapy, pp. 416– effectiveness of, pp. 426– Rorschach inkblot test, p. 355 Savant syndrome, pp. 238– Schizophrenia, pp. 401– parent- risk of, pp. 403– Self- Self- Sex- Sleep disorders, pp. 58– Spanked children, risk for aggression among, p. 181 Substance use disorders and addictive behaviors, pp. 385– Suicide, pp. 400– Testosterone replacement therapy, p. 116 Tolerance, withdrawal, and addiction, p. 386 |

Study System Follows Best Practices From Learning and Memory Research

This text’s learning system harnesses the testing effect, which documents the benefits of actively retrieving information through self-

In addition, each main section of text begins with a numbered question that establishes a learning objective and directs student reading. The Chapter Review section repeats these questions as a further self-

Retrieve + Remember

Question 401.1

•What does a good theory do?

ANSWER: 1. It organizes observed facts. 2. It implies hypotheses that offer testable predictions and, sometimes, practical applications. 3. It often stimulates further research.

Question 401.2

•Why is replication important?

ANSWER: When others are able to repeat (replicate) studies and produce similar results, psychologists can have more confidence in the original findings.

FIGURE 4 Sample of Retrieve + Remember feature

Each chapter closes with In Your Everyday Life questions, designed to help students make the concepts more personally meaningful, and therefore more memorable. These questions are also well designed to function as group discussion topics. The text offers hundreds of interesting applications to help students see just how applicable psychology’s concepts are to everyday life.

These features enhance the Survey-

Our LearningCurve formative quizzing in LaunchPad is built on these principles as well, allowing students to develop a personalized learning plan.

Multimedia for Psychology in Everyday Life, Fourth Edition

Psychology in Everyday Life, Fourth Edition, boasts impressive multimedia options. For more information about any of these choices, visit our online catalog at MacmillanLearning.com/

LaunchPad

LaunchPad (LaunchPadWorks.com) was carefully designed to solve key challenges in the course (see FIGURE 5). LaunchPad gives students everything they need to prepare for class and exams, while giving instructors everything they need to quickly set up a course, shape the content to their syllabus, craft presentations and lectures, assign and assess homework, and guide the progress of individual students and the class as a whole.

An interactive e-

Book integrates the text and all student media, including the “Assess Your Strengths” activities, “Immersive Learning: How Would You Know?” activities, and PsychSim 6 tutorials.LearningCurve adaptive quizzing gives individualized question sets and feedback based on each student’s correct and incorrect responses. All the questions are tied back to the e-

Book to encourage students to read the book in preparation for class time and exams. PsychSim 6 has arrived! Tom Ludwig’s (Hope College) fabulous new tutorials further strengthen LaunchPad’s abundance of helpful student activity resources.

The new Video Assignment Tool makes it easy to assign and assess video-

based activities and projects, and provides a convenient way for students to submit video coursework. LaunchPad Gradebook gives a clear window on performance for the whole class, for individual students, and for individual assignments.

A streamlined interface helps students manage their schedule of assignments, while social commenting tools let them connect with classmates, and learn from one another. 24/7 help is a click away, accessible from a link in the upper right-

hand corner. Page xxiiiWe [DM and ND] curated optional pre-

built chapter units, which can be used as is or customized. Or choose not to use them and build your course from scratch.Book-

specific instructor resources include PowerPoint sets, textbook graphics, lecture and activity suggestions, test banks, and more.LaunchPad offers easy LMS integration into your school’s learning management system.

Faculty Support and Student Resources

Instructor’s Resources available in LaunchPad

Lecture Guides available in LaunchPad

Macmillan Community (Community.Macmillan.com) Created by instructors for instructors, this is an ideal forum for interacting with fellow educators—

including Macmillan authors— in your discipline. Join ongoing conversations about everything from course prep and presentations to assignments and assessments to teaching with media, keeping pace with— and influencing— new directions in your field. Includes exclusive access to classroom resources, blogs, webinars, professional development opportunities, and more. Enhanced course management solutions (including course cartridges)

e-

Book in various available formats

Video and Presentation

The Video Collection is now the single resource for all videos for introductory psychology from Worth Publishers. Available on flash drive and in LaunchPad, this includes more than 130 clips.

Interactive Presentation Slides for Introductory Psychology is an extraordinary series of PowerPoint® lectures. This is a dynamic, yet easy-

to- use way to engage students during classroom presentations of core psychology topics. This collection provides opportunities for discussion and interaction, and includes an unprecedented number of embedded video clips and animations.

Assessment

LearningCurve quizzing in LaunchPad

Diploma Test Banks, downloadable from LaunchPad and our online catalog

Chapter Quizzes in LaunchPad

Clicker Question Presentation Slides now in PowerPoint®

Study Guide, by Richard O. Straub

Pursuing Human Strengths: A Positive Psychology Guide, Second Edition, by Martin Bolt and Dana S. Dunn

Critical Thinking Companion, Third Edition, by Jane S. Halonen and Cynthia Gray

FABBS Foundation’s Psychology and the Real World: Essays Illustrating Fundamental Contributions to Society, Second Edition, edited by Morton Ann Gernsbacher and James R. Pomerantz

The Horse That Won’t Go Away: Clever Hans, Facilitated Communication, and the Need for Clear Thinking, by Scott O. Lilienfeld, Susan A. Nolan, and Thomas Heinzen

The Psychology Major’s Companion: Everything You Need to Know to Get Where You Want to Go, by Dana S. Dunn and Jane S. Halonen

The Worth Expert Guide to Scientific Literacy: Thinking Like a Psychological Scientist, by Kenneth D. Keith and Bernard C. Beins

Collaboration in Psychological Science: Behind the Scenes, by Richard Zweigenhaft and Eugene Borgida

APA Assessment Tools

In 2011, the American Psychological Association (APA) approved the new Principles for Quality Undergraduate Education in Psychology. These broad-

APA’s more specific 2013 Learning Goals and Outcomes, from their Guidelines for the Undergraduate Psychology Major, Version 2.0, were designed to gauge progress in students graduating with psychology majors. (See apa.org/

Some instructors are eager to know whether a given text for the introductory course helps students get a good start at achieving these APA benchmarks. TABLE 6 outlines the way Psychology in Everyday Life, Fourth Edition, could help you to address the 2013 APA Learning Goals and Outcomes in your department. In addition, the Test Bank questions for Psychology in Everyday Life, Fourth Edition, are all keyed to these APA Learning Goals and Outcomes.

| Relevant Feature from Psychology in Everyday Life, Fourth Edition | APA Learning Goals | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Base in Psychology | Scientific Inquiry and Critical Thinking | Ethical and Social Responsibility in a Diverse World | Communication | Professional Development | |

| Text content | • | • | • | • | • |

| Four Big Ideas in Psychology as integrating themes | • | • | • | • | |

| “Thinking Critically About” features | • | • | • | • | |

| Learning Objective Questions previewing main sections | • | • | • | ||

| Retrieve + Remember sections throughout | • | • | • | • | • |

| In Your Everyday Life questions at end of each chapter | • | • | • | • | • |

| “Try this”-style activities integrated throughout | • | • | • | • | |

| Chapter Tests | • | • | • | ||

| Statistical Reasoning in Everyday Life appendix | • | • | • | ||

| Psychology at Work appendix | • | • | • | • | • |

| Subfields of Psychology appendix, with Careers in Psychology online appendix | • | • | • | ||

| LaunchPad with LearningCurve formative quizzing | • | • | • | • | • |

| “Assess Your Strengths” feature in LaunchPad | • | • | • | • | • |

| “Immersive Learning: How Would You Know?” activities in LaunchPad | • | • | • | • | • |

An APA working group in 2013 drafted guidelines for Strengthening the Common Core of the Introductory Psychology Course (tinyurl.com/

MCAT Now Includes Psychology

Since 2015, the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT) has devoted 25 percent of its questions to the “Psychological, Social, and Biological Foundations of Behavior,” with most of those questions coming from the psychological science taught in introductory psychology courses. From 1977 to 2014, the MCAT focused on biology, chemistry, and physics. Hereafter, reported the Preview Guide for MCAT 2015, the exam will also recognize “the importance of socio-

| MCAT 2015 | Psychology in Everyday Life, Fourth Edition, Correlations | |

|---|---|---|

| Content Category 6C: Responding to the world | Page Number | |

| Emotion | Emotion: Arousal, Behavior, and Cognition; Embodied Emotion; Expressed and Experienced Emotion | 270– |

| Three components of emotion (i.e., cognitive, physiological, behavioral) | Emotion: Arousal, Behavior, and Cognition | 270– |

| Universal emotions (e.g., fear, anger, happiness, surprise, joy, disgust, and sadness) | The Basic Emotions | 273– |

| Culture and Emotion— |

278– |

|

| Adaptive role of emotion | Emotion as the body’s adaptive response | 270 |

| Emotions and the Autonomic Nervous System | 274 | |

| Theories of emotion | ||

| James- |

James- |

271 |

| Cannon- |

Cannon- |

271 |

| Schachter- |

Schachter and Singer Two- |

271– |

| The role of biological processes in perceiving emotion | Emotions and the Autonomic Nervous System | 274 |

| Brain regions involved in the generation and experience of emotions | The Physiology of Emotions | 274 |

| Zajonc, LeDoux, and Lazarus: Emotion and the Two- |

272– |

|

| The role of the limbic system in emotion | Emotions and the Autonomic Nervous System | 274 |

| Physiological differences among specific emotions | 274– |

|

| Emotion and the autonomic nervous system | Emotions and the Autonomic Nervous System | 274 |

| Physiological markers of emotion (signatures of emotion) | The Physiology of Emotions | 274– |

| Stress | Stress, Health, and Human Flourishing | 284– |

| The nature of stress | Stress: Some Basic Concepts | 286– |

| Appraisal | Stress appraisal | 286 |

| Different types of stressors (i.e., cataclysmic events, personal) | Stressors— |

286– |

| Effects of stress on psychological functions | Stress Reactions— |

287– |

| Stress outcomes/response to stressors | Stress Reactions— |

287– |

| Physiological | Stress Reactions— |

287– |

| Stress Effects and Health | 288– |

|

| Emotional | Stress and Heart Disease— |

290– |

| Coping With Stress | 293– |

|

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder | 382– |

|

| Behavioral | Stress Reactions— |

287– |

| Coping With Stress | 293– |

|

| Managing stress (e.g., exercise, relaxation techniques, spirituality) | Managing Stress Effects— |

298– |

In Appreciation

Aided by input from thousands of instructors and students over the years, this has become a better, more effective, more accurate book than two authors alone (these authors at least) could write. Our indebtedness continues to the innumerable researchers who have been so willing to share their time and talent to help us accurately report their research, and to the hundreds of instructors who have taken the time to offer feedback.

Our gratitude extends to the colleagues who contributed criticism, corrections, and creative ideas related to the content, pedagogy, and format of this new edition and its teaching package. For their expertise and encouragement, and the gift of their time to the teaching of psychology, we thank the reviewers and consultants listed here.

Matthew Alcala Santa Ana College

Burton Beck Pensacola State College

LaQuisha Beckum De Anza College

Gina Bell Santa Barbara City College

Bucky Bhadha Pasadena City College

Gerald Braasch McHenry County College

T. L. Brink Cosumnes River College

Eric Bruns Campbellsville University

Carrie Canales West Los Angeles College

Michael Cassens Irvine Valley College

Wilson Chu Cerritos College

Jeffrey Cooley University of Wisconsin–

Amy Cunningham San Diego Mesa College

Robert DuBois Waukesha County Technical College

Michael Fantetti Western New England University

Jessica Fede Johnson and Wales University

Perry Fuchs University of Texas at Arlington

Marcus Galle University of Texas Rio Grande Valley

Caroline Gee Saddleback College

Emily Germain Southern Wesleyan University

Pavithra Giridharan Middlesex Community College

Allyson Graf Elmira College

Philippe Gross Kapi’olani Community College

Christopher Hayashi Southwestern College

Ann Hennessey Los Angeles Pierce College

Julia Hoigaard Fullerton College

Lindsay Holland Chattanooga State Community College

Michael Huff College of the Canyons

Lynn Ingram University of North Carolina, Wilmington

Linda Johnson Butte College

Andrew Kim Citrus College

Kristie Knows His Gun George Fox University

Misty Kolchakian Mt. San Antonio College

Linda Krajewski Norco College

Marika Lamoreaux Georgia State University

Kelly Landman Delaware County Community College

Karen Markowitz Grossmont College

Jan Mendoza Golden West College

Peter Metzner Vance-

Josh Muller College of the Sequoias

Hayley Nelson Delaware County Community College

David Oberleitner University of Bridgeport

Susan O’Donnell George Fox University

Ifat Pelad College of the Canyons

Lien Pham Orange Coast College

Debra Phoenix Maher Orange Coast College

Jack Powell University of Hartford

Joseph Reish Tidewater Community College

Ja Ne’t Rommero Mission College

Edie Sample Metropolitan Community College-

Meridith Selden Yuba College

Aya Shigeto Nova Southeastern University

Michael Skibo Westchester Community College

Bradley Stern Cosumnes River College

Leland Swenson California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo

Shawn Ward Le Moyne College

Jane Whitaker University of the Cumberlands

Judith Wightman Kirkwood Community College

Ellen Wilson University of Wisconsin–

We appreciate the guidance offered by the following teaching psychologists, who reviewed and offered helpful feedback on the development of our “Assess Your Strengths” LaunchPad activities, or on our new “Immersive Learning: How Would You Know?” feature in LaunchPad. (See LaunchPadWorks.com.)

“Assess Your Strengths” Activity Reviewers

Malinde Althaus, Inver Hills Community College

TaMetryce Collins, Hillsborough Community College, Brandon

Lisa Fosbender, Gulf Coast State College

Kelly Henry, Missouri Western State University

Brooke Hindman, Greenville Technical College

Natalie Kemp, University of Mount Olive

David Payne, Wallace Community College

Tanya Renner, Kapi’olani Community College

Lillian Russell, Alabama State University, Montgomery

Amy Williamson, Moraine Valley Community College

“Immersive Learning: How Would You Know?” Activity Reviewers

Pamela Ansburg, Metropolitan State University of Denver

Makenzie Bayles, Jacksonville State University

Lisamarie Bensman, University of Hawai’i at Manoa

Jeffrey Blum, Los Angeles City College

Pamela Costa, Tacoma Community College

Jennifer Dale, Community College of Aurora

Michael Devoley, Lone Star College, Montgomery

Rock Doddridge, Asheville-

Kristen Doran, Delaware County Community College

Nathaniel Douda, Colorado State University

Celeste Favela, El Paso Community College

Nicholas Fernandez, El Paso Community College

Nathalie Franco, Broward College

Sara Garvey, Colorado State University

Nichelle Gause, Clayton State University

Michael Green, Lone Star College, Montgomery

Christine Grela, McHenry County College

Rodney Joseph Grisham, Indian River State College

Toni Henderson, Langara College

Jessica Irons, James Madison University

Darren Iwamoto, Chaminade University of Honolulu

Jerwen Jou, University of Texas, Pan American

Rosalyn King, Northern Virginia Community College, Loudoun Campus

Claudia Lampman, University of Alaska, Anchorage

Mary Livingston, Louisiana Tech University

Christine Lofgren, University of California, Irvine

Thomas Ludwig, Hope College

Theresa Luhrs, DePaul University

Megan McIlreavy, Coastal Carolina University

Elizabeth Mosser, Harford Community College

Robin Musselman, Lehigh Carbon Community College

Kelly O’Dell, Community College of Aurora

William Keith Pannell, El Paso Community College

Eirini Papafratzeskakou, Mercer County Community College

Jennifer Poole, Langara College

James Rodgers, Hawkeye Community College

Regina Roof-

Lisa Routh, Pikes Peak Community College

Conni Rush, Pittsburg State University

Randi Smith, Metropolitan State University of Denver

Laura Talcott, Indiana University, South Bend

Cynthia Turk, Washburn University

Parita Vithlani, Harford Community College

David Williams, Spartanburg Community College

We offer thanks to the three dozen instructors who thoughtfully responded to our new edition planning survey, from the following schools:

Allan Hancock College

Antelope Valley College

Bakersfield College

Barstow Community College

Bristol Community College

California State University, Chico

California State University, Long Beach

Cerritos College

Chaffey College

Chandler Gilbert Community College

Dallas County Community College

John Carroll University

Johnson & Wales University

Lincoln University

Middlesex Community College

North Lake College

Northampton Community College

Northern Essex College

Northern Kentucky University

Paradise Valley Community College

Pensacola State College

Rowan University

Sierra College

Suffolk County Community College

Tennessee State University

University of Wisconsin-

Upper Iowa University

Utica College

Valdosta State University

Yuba College

And we appreciate the input from the students who helped us select the best of the application questions from the text, to appear inside the front and back covers of this new edition. Those students represent the following schools:

College of St. Benedict

Cornell University

Creighton University

Fordham University

George Washington University

Hofstra University

Hope College

James Madison University

State University of New York at Geneseo

University of Kentucky

University of New Hampshire

At Worth Publishers a host of people played key roles in creating this fourth edition.

Noel Hohnstine and Laura Burden coordinated production of the huge media component for this edition, including the fun Assess Your Strengths activities. Betty Probert effectively edited and produced print and media supplements and, in the process, also helped fine-

Tracey Kuehn, Director of Content Management Enhancement, displayed tireless tenacity, commitment, and impressive organization in leading Worth’s gifted artistic production team and coordinating editorial input throughout the production process. Project Editor Won McIntosh and Senior Production Supervisor Sarah Segal masterfully kept the book to its tight schedule, and Director of Design Diana Blume and Senior Design Manager Blake Logan skillfully created the beautiful new design program.

As you can see, although this book has two authors it is a team effort. A special salute is due to two of our book development editors, who have invested so much in creating Psychology in Everyday Life. My [DM] longtime editor Christine Brune saw the need for a very short, accessible, student-

To achieve our goal of supporting the teaching of psychology, this teaching package not only must be authored, reviewed, edited, and produced, but also made available to teachers of psychology, with effective guidance and professional and friendly servicing close at hand. For their exceptional success in doing all this, our author team is grateful to Macmillan Learning’s professional sales and marketing team. We are especially grateful to Executive Marketing Manager Kate Nurre, Senior Marketing Manager Lindsay Johnson, and Learning Solutions Specialist Nicki Trombley both for their tireless efforts to inform and guide our teaching colleagues about our efforts to assist their teaching, and for the joy of working with them.

At Hope College, the supporting team members for this edition included Kathryn Brownson, who researched countless bits of information and edited and proofed hundreds of pages. Kathryn is a knowledgeable and sensitive adviser on many matters, and Sara Neevel is our high-

Again, I [DM] gratefully acknowledge the editing assistance and mentoring of my writing coach, poet Jack Ridl, whose influence resides in the voice you will be hearing in the pages that follow. He, more than anyone, cultivated my delight in dancing with the language, and taught me to approach writing as a craft that shades into art. Likewise, I [ND] am grateful to my intellectual hero and mentor, Roy Baumeister, who taught me how to hone my writing and embrace the writing life.

After hearing countless dozens of people say that this book’s resource package has taken their teaching to a new level, we reflect on how fortunate we are to be a part of a team in which everyone has produced on-

And we have enjoyed our ongoing work with each other! It has been a joy for me [DM] to welcome Nathan into this project. Nathan’s fresh insights and contributions are enriching this book as we work together on each chapter. With support from our wonderful editors, this is a team project. In addition to our work together on the textbook, Nathan and I contribute to the monthly Teaching Current Directions in Psychological Science column in the APS Observer (tinyurl.com/

Finally, our gratitude extends to the many students and instructors who have written to offer suggestions, or just an encouraging word. It is for them, and those about to begin their study of psychology, that we have done our best to introduce the field we love.

* * *

The day this book went to press was the day we started gathering information and ideas for the next edition. Your input will influence how this book continues to evolve. So, please, do share your thoughts.

Hope College

Holland, Michigan 49422-

DavidMyers.org

myers@hope.edu

@DavidGMyers

University of Kentucky

Lexington, Kentucky 40506-

NathanDeWall.com

nathan.dewall@uky.edu

@cndewall