When an organism must reach toward the sun for the energy to make its own food, gravity can be the enemy. Plants compete with each other, and taller plants can leave shorter plants in the shade, with reduced access to sunlight. The body of a plant is one continuous structure, with the root system below ground and a portion called the shoot system above ground. The shoot is divided into two parts: stems and leaves. In some species, the shoot system also includes flowers and fruits, the reproductive structures, which we discuss in Chapter 18.

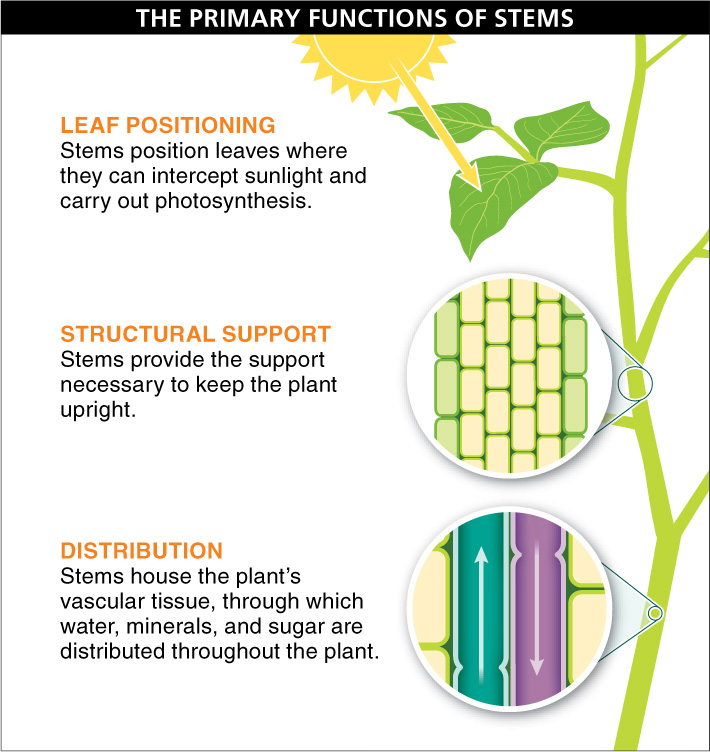

Serving as the backbone of the plant, the stem provides structural support for the plant. And in conjunction with the roots, the stem enables the plant to grow and orient its leaves toward the sun. The stem’s third function is housing the plant’s transport infrastructure—

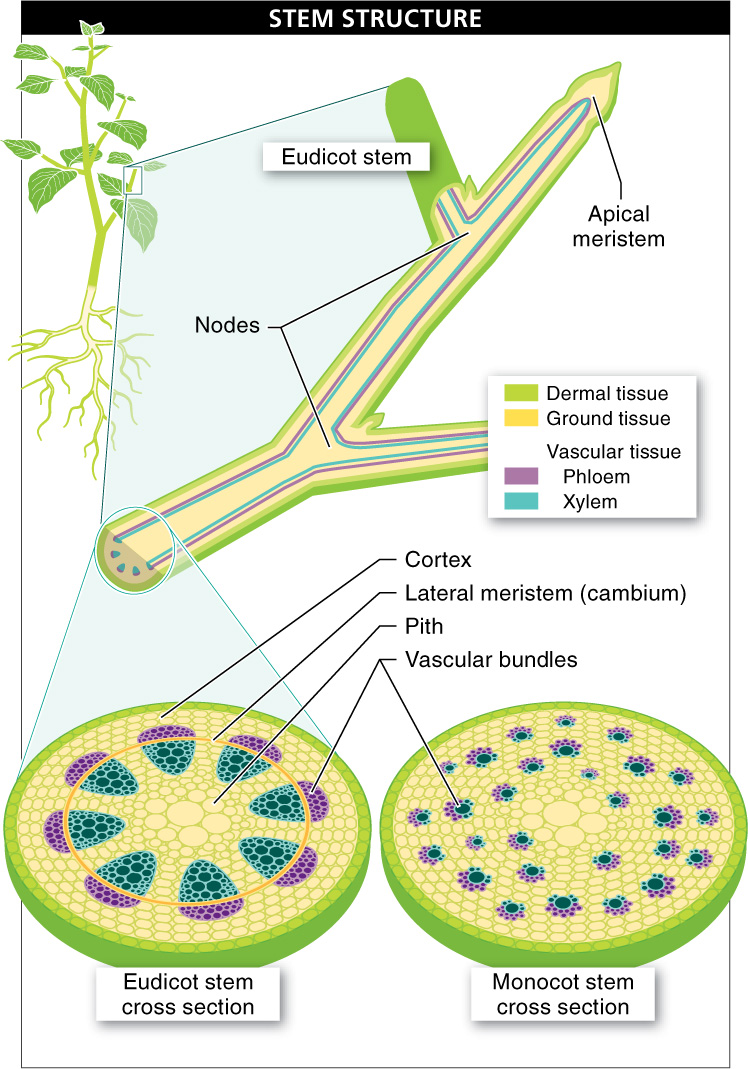

In plants, growth occurs in regions called meristems, made up of undifferentiated cells. These cells divide, often at very high rates, generating additional meristem cells along with cells that differentiate into epidermis, vascular tissue, or ground tissue. At the tip of a root or stem, the meristem is called an apical meristem, and division of cells there causes the root or stem to increase in length. Lateral meristems, on the other hand, consist of a layer of cells, called cambium, that cause a stem or root to become thicker, as opposed to longer, when they divide. We discuss plant growth in more detail in Chapter 18.

698

Stem growth and root growth are similar, except that stem growth has the added complexity that it is segmented (FIGURE 17-14). That is, the stem grows a bit and then produces nodes, little lumps of tissue from which leaves, flowers, cones, or additional stems (or even a branch) may grow.

The stems of flowering plants contain vascular bundles. (Recall that there are two types of pipelines through which sap, containing essential fluids and chemicals, is transported: water and minerals move through the xylem, and sugars move through the phloem.) As we saw in Section 17-

699

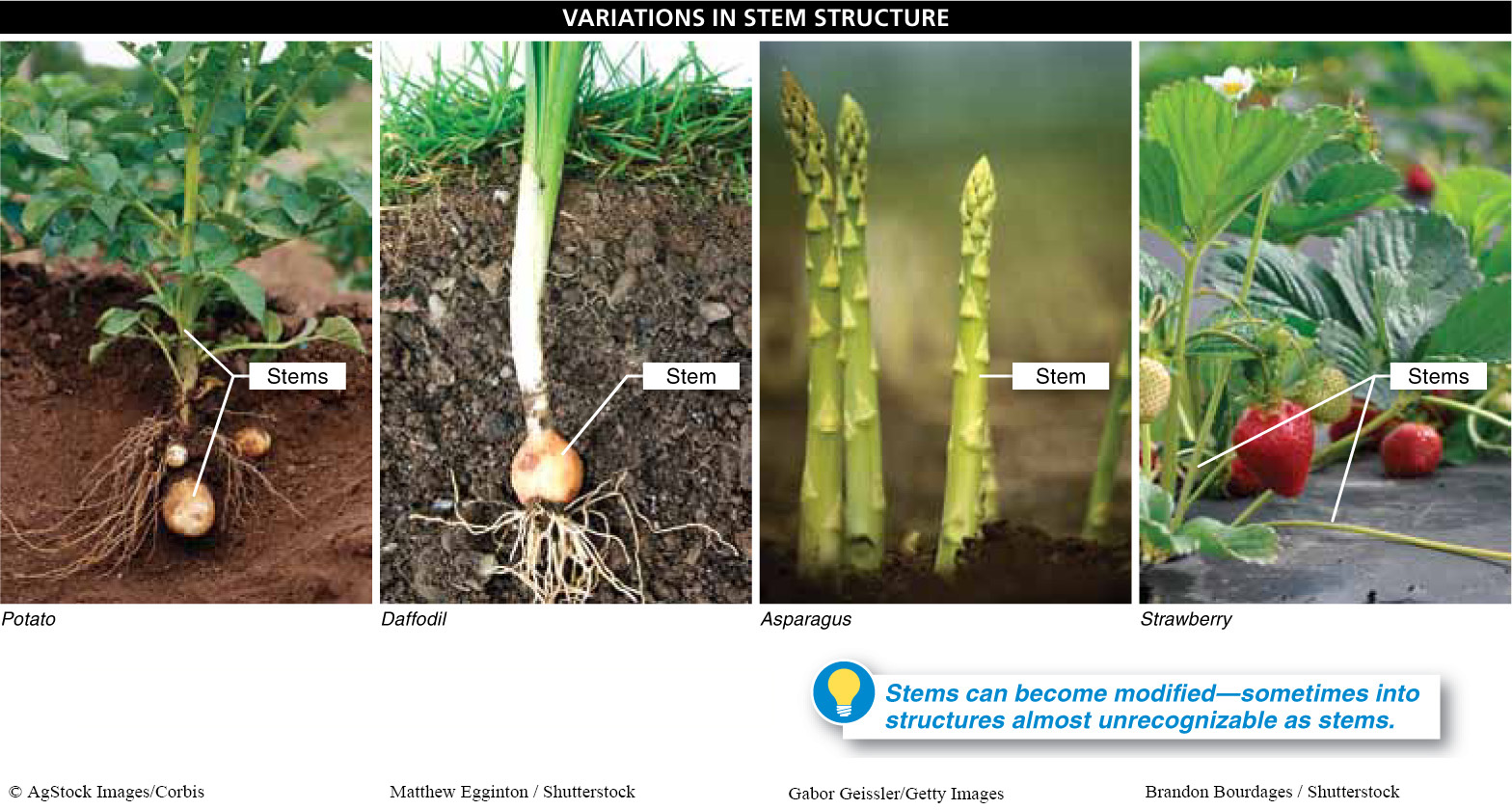

If we started slicing up the stems of all the plants around us, it would quickly become clear that there isn’t one single design for all stems. Although the stems of all flowering plants are variations on the two themes described here, they vary tremendously (FIGURE 17-15). Most of the bulbs that gardeners plant each year, such as those for daffodils and lilies, are stems. Many modified leaves are attached to the bulb stems, forming the bulk of the bulb, and, after planting, the roots emerge from the bottom.

Some of our favorite foods come from modified stem tissue. Asparagus spears, for example, are fleshy stems. If you look closely, you can see what appear to be scales along the spear and at the tip. These are actually very tiny leaves that haven’t branched off very far from the stem. Broccoli and cauliflower also include modified stem. Also, the horizontal runners of a strawberry plant are stems, from which roots emerge at regular intervals to anchor the plant and stems to the ground. And growing underground, potatoes, too, are highly modified branching stems—

As stems grow and branch, they increase in girth and length, becoming stronger and better able to position leaves where they can have adequate exposure to the sun for making food through photosynthesis. In the next chapter, we investigate the process by which stems develop into tree trunks and, in doing so, produce wood—

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE 17.5

Stems serve three chief functions in plants: (1) they put leaves in positions where they can intercept sunlight and carry out photosynthesis; (2) they provide structural support for the plant; and (3) they contain the xylem and phloem, through which water, minerals, and sugars are distributed throughout the plant body.

You slice into the stems of two different flowering plants. You observe that one has vascular bundles arranged in a ring, much like a clock face, whereas the other has vascular bundles randomly dispersed throughout the stem. What can you conclude about each plant?

This is indicative of the two major groups of flowering plants: eudicots have a ring of vascular bundles (like a clock face), whereas monocots have vascular bundles randomly dispersed throughout the stem.