17.6 Some Genes Are Regulated by Processes That Affect Translation or by Modifications of Proteins

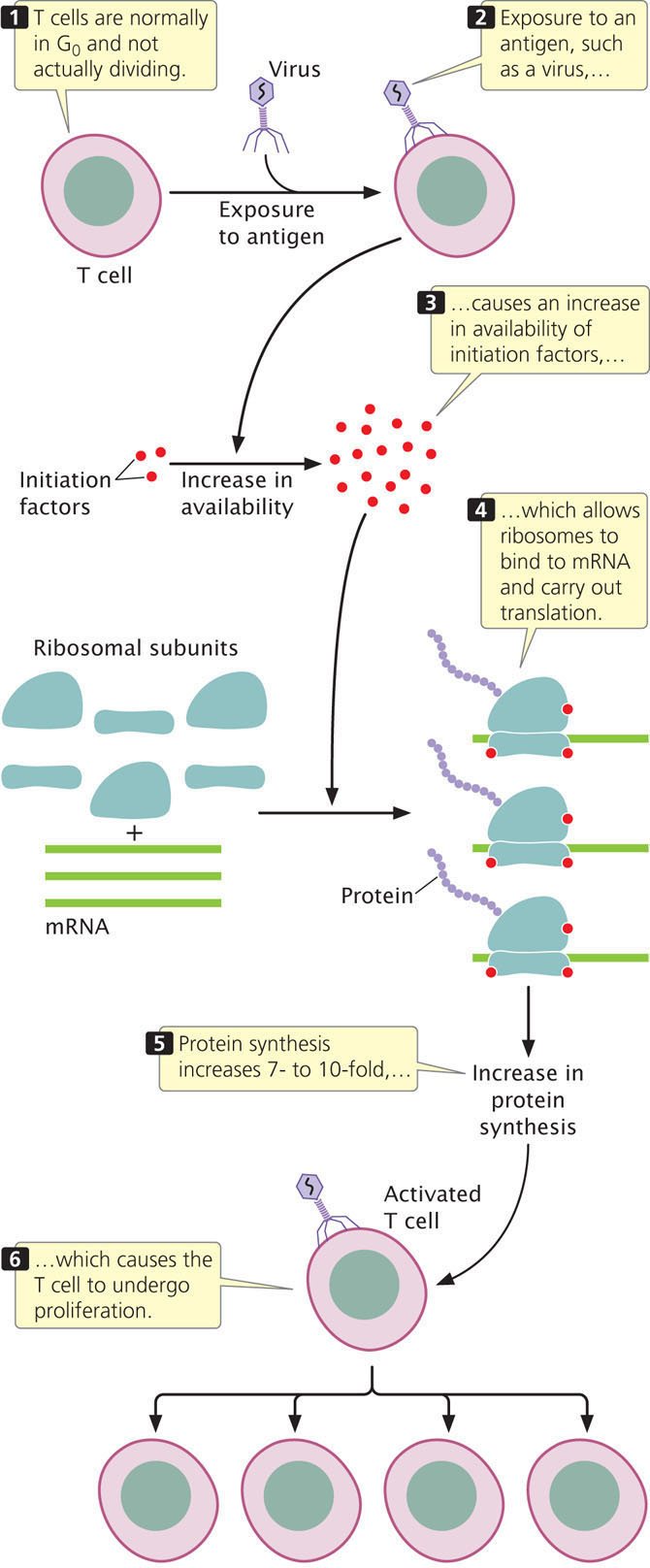

Ribosomes, aminoacyl tRNAs, initiation factors, and elongation factors are all required for the translation of mRNA molecules. The availability of these components affects the rate of translation and therefore influences gene expression. For example, the activation of T lymphocytes (T cells) is critical to the development of immune responses to viruses (see Chapter 22). T cells are normally in the G0 stage of the cell cycle and not actively dividing. On exposure to viral antigens, however, specific T cells become activated and undergo rapid proliferation (Figure 17.14). Activation includes a 7- to 10-fold increase in protein synthesis that causes cells to enter the cell cycle and proliferate. This burst of protein synthesis does not require an increase in mRNA synthesis. Instead, a global increase in protein synthesis is due to the increased availability of initiation factors taking part in translation—initiation factors that allow ribosomes to bind to mRNA and begin translation. This increase in initiation factors leads to more translation from the existing mRNA molecules, increasing the overall amount of protein synthesized. Similarly, insulin stimulates the initiation of overall protein synthesis by increasing the availability of initiation factors. Initiation factors exist in inactive forms and, in response to various cell signals, can be activated by chemical modifications of their structure, such as phosphorylation.

Mechanisms also exist for the regulation of translation of specific mRNAs. The initiation of translation in some mRNAs is regulated by proteins that bind to an mRNA’s 5′ UTR and inhibit the binding of ribosomes, similar to the way in which repressor proteins bind to operators and prevent the transcription of structural genes. The translation of some mRNAs is affected by the binding of proteins to sequences in the 3′ UTR.

Many eukaryotic proteins are extensively modified after translation by the selective cleavage and trimming of amino acids from the ends, by acetylation, or by the addition of phosphate groups, carboxyl groups, methyl groups, or carbohydrates to the protein. These modifications affect the transport, function, and activity of the proteins.

CONCEPTS

The initiation of translation may be affected by proteins that bind to specific sequences at the 5′ end of mRNA. The availability of ribosomes, tRNAs, initiation and elongation factors, and other components of the translational apparatus may affect the rate of translation. Translation of some mRNAs is regulated by proteins that bind to the 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions of the mRNA.

CONNECTING CONCEPTS

Now that we have considered the major types of gene regulation in bacteria (Chapter 16) and eukaryotes (this chapter), let’s consider some of the similarities and differences in bacterial and eukaryotic gene control.

- Much of gene regulation in bacterial cells is at the level of transcription (although it does exist at other levels). Gene regulation in eukaryotic cells takes place at multiple levels, including chromatin structure, transcription, mRNA processing, RNA stability, RNA interference, and posttranslational control.

- Complex biochemical and developmental events in bacterial and eukaryotic cells may require a cascade of gene regulation, in which the activation of one set of genes stimulates the activation of another set.

- Much of gene regulation in both bacterial and eukaryotic cells is accomplished through proteins that bind to specific sequences in DNA. Regulatory proteins come in a variety of types, but most can be characterized according to a small set of DNA-binding motifs.

- Chromatin structure plays a role in eukaryotic (but not bacterial) gene regulation. In general, condensed chromatin represses gene expression; chromatin structure must be altered before transcription can take place. Chromatin structure is altered by the chromatin-remodeling proteins, modification of histone proteins, and DNA methylation.

- Modifications to chromatin structure in eukaryotes may lead to epigenetic changes, which are changes that affect gene expression and are passed on to other cells or future generations.

- In bacterial cells, genes are often clustered in operons and are coordinately expressed by transcription into a single mRNA molecule. In contrast, many eukaryotic genes have their own promoters and are transcribed independently. Coordinated regulation in eukaryotic cells often takes place through common response elements, present in the promoters and enhancers of the genes. Different genes that have the same response element in common are influenced by the same regulatory protein.

- Regulatory proteins that affect transcription exhibit two basic types of control: repressors inhibit transcription (negative control); activators stimulate transcription (positive control). Both negative control and positive control are found in bacterial and eukaryotic cells.

- The initiation of transcription is a relatively simple process in bacterial cells, and regulatory proteins function by blocking or stimulating the binding of RNA polymerase to DNA. In contrast, eukaryotic transcription requires complex machinery that includes RNA polymerase, general transcription factors, and transcriptional activators, which allows transcription to be influenced by multiple factors.

- Some eukaryotic transcriptional regulatory proteins function at a distance from the gene by binding to enhancers, causing the formation of a loop in the DNA, which brings the promoter and enhancer into close proximity. Some distant-acting sequences analogous to enhancers have been described in bacterial cells, but they appear to be less common.

- The greater time lag between transcription and translation in eukaryotic cells compared with that in bacterial cells allows mRNA stability and mRNA processing to play larger roles in eukaryotic gene regulation.

- RNA molecules (antisense RNA) may act as regulators of gene expression in bacteria. Regulation by siRNAs and miRNAs, which is extensive in eukaryotes, is absent from bacterial cells.

These similarities and differences in gene regulation of bacteria and eukaryotes are summarized in Table 17.2.

| Characteristic | Bacterial Gene Control | Eukaryotic Gene Control |

|---|---|---|

| Levels of regulation | Primarily transcription | Many levels |

| Cascades of gene regulation | Present | Present |

| DNA binding proteins | Important | Important |

| Role of chromatin structure | Absent | Important |

| Presence of operons | Common | Uncommon |

| Negative and positive control | Present | Present |

| Initiation of transcription | Relatively simple | Relatively complex |

| Enhancers | Less common | More common |

| Transcription and translation | Occur simultaneously | Occur separately |

| Regulation by small RNAs | Rare | Common |