THE ROLE OF BACTERIA IN THE GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT

PROBIOTICS live, beneficial bacteria found in fermented foods that can restore or maintain a healthy balance of “friendly” bacteria in GI tract

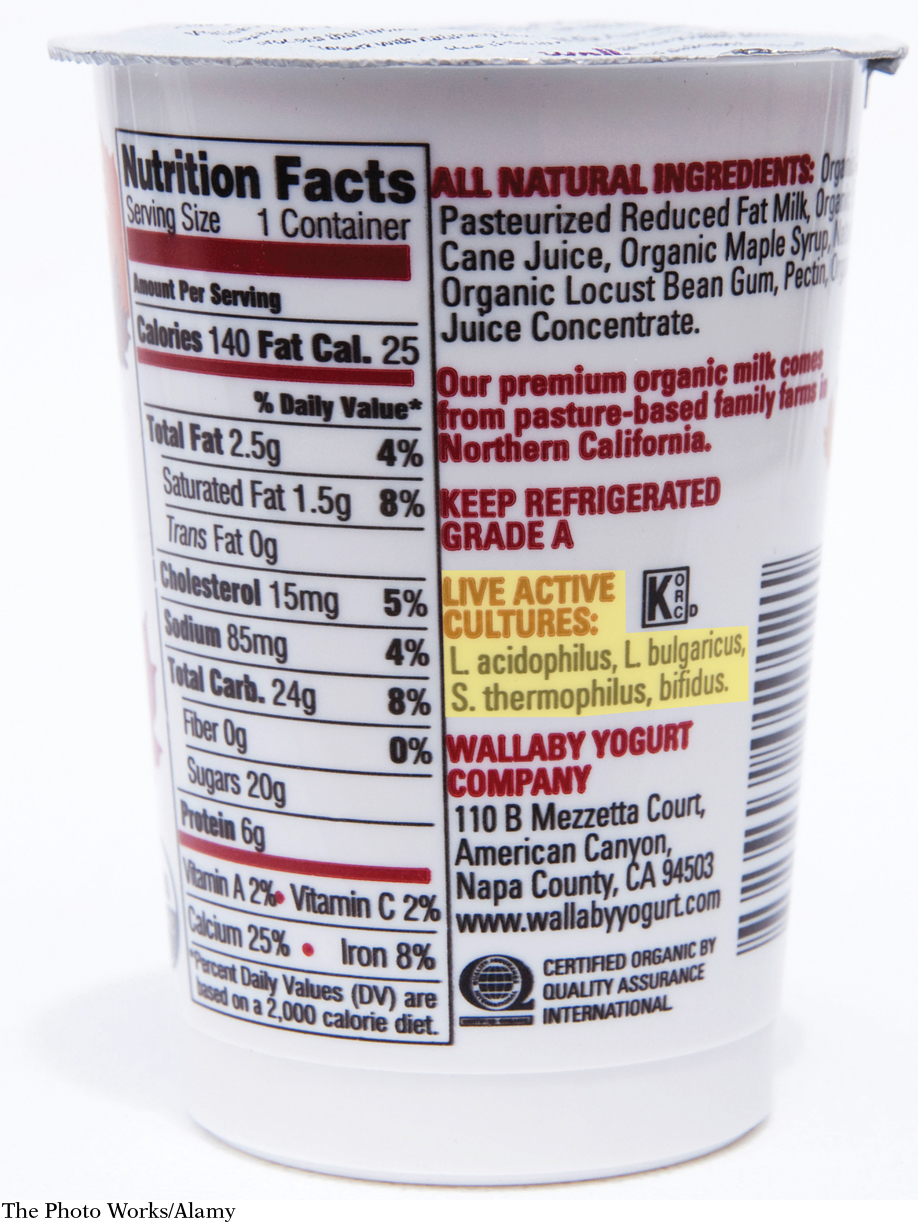

Some of the most helpful bacteria are known as probiotics—a word you may have seen on food or beverage labels. Food manufacturers highlight the probiotics in their products because these bacteria help restore or maintain a healthy balance of “friendly” bacteria in the GI tract. Although some manufacturers add probiotics to their products, probiotics are found naturally in fermented foods, such as dairy products like yogurts, buttermilk, and cottage cheese. Other fermented sources of probiotics include soy, tempeh, miso, and sauerkraut.

PREBIOTICS nondigestible carbohydrates broken down by colon bacteria that foster the growth of good bacteria

A healthy diet should also contain plenty of prebiotics, certain types of nondigestible carbohydrates that healthy bacteria use to boost their growth in the large intestine. (You can think of prebiotics as substances that “feed” or nourish good bacteria.) Eating prebiotics may prevent and treat diarrhea and colon cancer, boost the absorption of minerals, reduce levels of fat in the blood, and help control blood glucose. Some of these benefits may result from the short-

Scanning the prebiotic list above, you’ll notice that some of those foods—

Even though celiac disease does its damage in the small intestine, its effects are felt throughout the body. That’s because the immune cells that start attacking the villi of the small intestine eventually go somewhere else. “Celiac starts in the small intestine, but any organ in the body can be affected,” Fasano says. He has seen patients with celiac disease and no stomach problems, for instance, but who have anemia or damage to the liver. The pancreas can also be damaged by these immune cells, rendering it less able to produce hormones that regulate metabolism, such as insulin.

■ ■ ■