Economic and Political Issues

Geographic Insight 3

Globalization and Development: Globalization, coupled with a greater focus on neighboring Asia (rather than on long-time connections with Europe), has transformed patterns of trade and economic development across Oceania.

The forces of globalization, driven largely by Asia’s growing affluence and enormous demand for resources, are shifting trade, migration, and tourism patterns within Oceania.

Globalization, Development, and Oceania’s New Asian Orientation

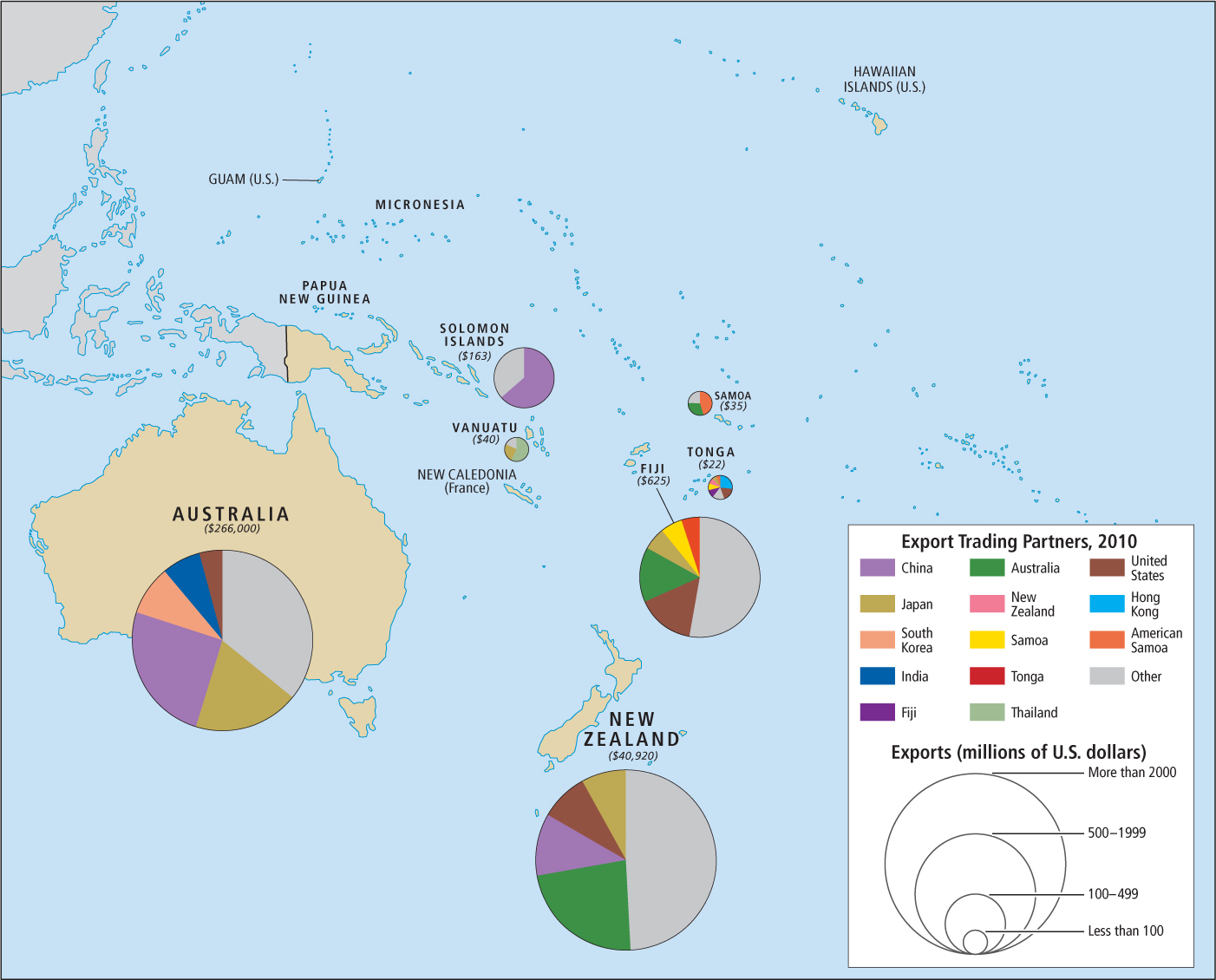

One could say that globalization in Oceania began when the first European explorers came into the region, beginning the trend of influence by outsiders (primarily Europeans) on settlement, culture, and economics. More recently, the United States has exerted a powerful influence on trade and politics in the region. For the past several decades, however, globalization has reoriented this region toward Asia, which buys more than 76 percent of Australia’s exports (mainly coal, iron ore, and other minerals). In 2011, China and India each purchased major shares of Australia’s coal deposits, not just the output of mines. Both countries use coal to generate energy and are trying to secure future access to more coal. Asia also buys nearly 35 percent of New Zealand’s exports (mainly meat, wool, and dairy products), as well as many other products and services from islands across Oceania (Figure 11.15).

Asia is also increasingly the source of the region’s imports. Because there is little manufacturing in Oceania, most manufactured goods are imported from China, Japan, South Korea, Singapore, and Thailand—Oceania’s leading trading partners. Both Australia and New Zealand have free trade agreements either completed or in continuous negotiation with Asia’s two largest economies, China and Japan.

The Pacific islands are further along in their reorientation toward Asia than are Australia and New Zealand. Not only are coconut, forest, and fish products from the Pacific islands sold to Asian markets, but Asian companies increasingly own these industries on the various islands. Fishing fleets from Asia regularly ply the offshore waters of Pacific island nations. Asians also dominate the Pacific island tourist trade, both as tourists and as investors in tourism infrastructure. And increasing numbers of Asians are taking up residence in the Pacific islands, exerting widespread economic and social influence.

The Stresses of Asia’s Economic Development “Miracle” on Australia and New Zealand

For Australia and New Zealand, Asia’s global economic rise has meant not only increased trade but also increased competition with Asian economies in foreign markets. Throughout Oceania, local industries used to enjoy protected or preferential trade with Europe. They have lost that advantage because EU regulations stemming from the EU’s membership in the World Trade Organization prohibit such arrangements. No longer protected in their trade with Europe, local industries now face stiff competition from larger companies in Asia that benefit from much cheaper labor.

Australia and New Zealand are somewhat unusual in having achieved broad prosperity largely on the basis of exporting raw materials over a long period of time and to a wide range of customers (see Figures 11.14E and 11.15). Preferential trade with Europe allowed higher profits for many export industries. Very important is the fact that strong labor movements in Australia and New Zealand meant that these industries’ profits were more equitably distributed throughout society than the profits in other raw materials–based economies in Middle and South America and sub-Saharan Africa. Australian coal miners’ unions successfully agitated not just for good wages, but also for the world’s first 35-hour workweek. Other labor unions won a minimum wage, pensions, and aid to families with children long before such programs were enacted in many other industrialized countries. For decades, these arrangements were highly successful. Both Australia and New Zealand enjoyed living standards comparable to those in North America but with a more egalitarian distribution of income. However, since the 1970s, competition from Asian companies has meant that increasing numbers of workers in Australia and New Zealand have lost jobs and seen their hard-won benefits scaled back or eliminated.

Competition from Asian companies also led to lower corporate profits in Oceania. As corporate profits fell, so did government tax revenues, which necessitated cuts to previously high rates of social spending on welfare, health care, and education. The loss of social support, especially for those who have lost jobs, has contributed to rising poverty in recent years. Australia now has the second-highest poverty rate in the industrialized world. (The United States has the highest.)

Maintaining Raw Materials Exports as Service Economies Develop

The shift toward trading more with Asia than with Europe or North America has had little effect on Oceania’s dependence on exporting unprocessed raw materials, because most Asian economies have a much greater need to import raw materials (rather than manufactured goods). Nevertheless, although their dollar contribution to national economies remains high, industries that export raw materials are of decreasing prominence in the economies of Australia and New Zealand, in that they now employ fewer people because of mechanization. This shift to lower labor requirements has been essential for these industries to stay globally competitive with other countries that use much cheaper labor.

Today, the economies of both Australia and New Zealand are dominated by diverse and growing service sectors, which have links to the region’s export sectors. Extracting minerals and managing herds and cropland have become technologically sophisticated enterprises that depend on many supporting services and an educated workforce. Australia is now a world leader in providing technical and other services to mining companies, sheep farms, and winemakers. Meanwhile, New Zealand’s well-educated workforce and well-developed marketing infrastructure have helped it break into luxury markets for dairy products, meats, and fruits. Perhaps the most visible success has been New Zealand’s global marketing of the indigenous kiwifruit. (In fact, kiwi is now a slang term for anyone from New Zealand.)

Economic Change in the Pacific Islands

In general, the Pacific islands are also shifting away from extractive industries, such as mining and fishing, and toward service industries such as tourism and government. On many islands, self-sufficiency and resources from abroad cushion the stress of economic change. Many households still construct their own homes and rely on fishing and subsistence cultivation for much of their food supply. On the islands of Fiji, for example, part-time subsistence agriculture engages more than 60 percent of the population, although it accounts for just under 17 percent of the economy. Remittances sent home from the thousands of Pacific Islanders working abroad are essential to many Pacific island economies and account for more than half of all income on some islands. However, remittances rarely make it into official statistics.

MIRAB economy an economy based on migration, remittance, aid, and bureaucracy

subsistence affluence a lifestyle whereby people are self-sufficient with regard to most necessities and have some opportunities to earn cash for travel and occasional purchases of manufactured goods

The Advantages and Stresses of Tourism

Tourism is a growing part of the economy throughout Oceania, with tourists coming largely from Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Southeast Asia, the Americas, and Europe (Figure 11.16). In 2008 (the latest year for which complete figures are available), 17.7 million tourists arrived in Oceania. Of the tourists visiting Oceania, 23 percent came from Asia—16 percent from Japan alone; just 11 percent came from Europe, down from 17 percent in recent years; 33 percent came from North America; 19 percent were from within Oceania; and 12 percent came from other locations.

In some Pacific island groups, the number of tourists far exceeds the island population. Guam, for example, annually receives tourists in numbers equivalent to five times its population. Palau and the Northern Mariana Islands annually receive more than four times their populations. Such large numbers of visitors, expecting to be entertained and graciously accommodated, can place a special stress on local inhabitants. And although they bring money to the islands’ economies, these visitors create problems for island ecology, place extra burdens on water and sewer systems, and require a standard of living that may be far out of reach for local people. Perhaps nowhere in the region are the issues raised by tourism clearer than in Hawaii.

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Subsistence Affluence Practices Could Go Global

Many of the qualities of subsistence affluence practiced by Pacific Islanders, including local self-sufficiency and resource conservation strategies, have the potential for being elaborated upon and adapted elsewhere in the region and across the world.

A Case Study: Conflict over Tourism in Hawaii

Since the 1950s, travel and tourism have been the largest industries in Hawaii, producing nearly 18 percent of the gross state product in 2008. Tourism is related in one way or another to nearly 75 percent of all jobs in the state. (By comparison, travel and tourism account for 9 percent of GDP worldwide.) In 2008, tourism employed one out of every six Hawaiians and accounted for 25 percent of state tax revenues.

Dramatic fluctuations in tourist visits, often driven by forces far removed from Oceania, can wreak havoc on local economies. Decreases in tourism affect not just tourist facilities but supporting industries, too. For example, construction thrives by building condominiums, hotels, resorts, and retirement facilities. The Asian recession of the late 1990s, the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, and the global recession of 2008–2009 all affected Hawaii’s economy by creating dramatic slumps in tourist visits. In 2011, however, Hawaii’s tourism industry rebounded: more than 7 million visitors arrived that year, up 11 percent over 2009.

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

APEC, a Regional Economic Association with a Broader View

APEC, which stands for “Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation,” is a forum for 21 “Pacific Rim” countries to discuss economic issues. However, in recent years it has extended its focus to address issues such as securing the Asia–Pacific food supply, reducing vulnerability to global climate change, finding energy-efficient means of transportation, developing financial institutions for small businesses, and training teams to handle pandemics. While APEC has no means of compelling its member countries to act, it is raising the profile of many crucial long-term concerns for Oceania.

Sometimes mass tourism can seem like an invading force to ordinary citizens. For example, an important segment of the Honolulu tourist infrastructure—hotels, golf courses, specialty shopping centers, import shops, and nightclubs—is geared to visitors from Japan, and many such facilities are owned by Japanese investors. Hawaiian citizens and other non-Japanese shoppers and vacationers can feel out of place.

Another example of the impositions of mass tourism is the demand by tourists for golf courses on many of the Hawaiian Islands, which resulted in what Native (indigenous) Hawaiians view as desecration of sacred sites. Land that in precolonial times was communally owned, cultivated, and used for sacred rituals was confiscated by the colonial government and more recently sold to Asian golf course developers. Now the only people with access to the sacred sites are fee-paying tourist golfers. As of 2012 there were more than 90 golf courses in Hawaii, and the golf industry alone contributed $1.6 billion to the state’s economy—more than twice the amount from agriculture. Golf’s total impact is $2.5 billion, which represents about 12.5 percent of the state’s tourism sector income. Relocation to Hawaii by retired Americans looking for a sunny spot—often called residential tourism—has also had an effect on property values and the use of sacred lands by local citizens. [Source: Hawaii Tourism Authority; and a field report from Conrad M. Goodwin and Lydia Pulsipher. For detailed source information, see Text Credit pages.]

Sustainable Tourism

Some Pacific islands have attempted to deal with the pressures of tourism by adopting the principle of sustainable tourism, which aims to decrease tourism’s imprint and minimize disparities between hosts and visitors. Samoa, for example, has created the Samoan Tourism Authority in conjunction with the South Pacific Regional Environment Programme. (Samoa refers to the independent country that was formerly known as Western Samoa; that country is politically distinct from American Samoa, a U.S. territory.) With financial aid from New Zealand, the Authority develops and monitors sustainable tourism components (beaches, wetlands, and forested island environments) and provides knowledge-based tourism experiences for visitors (information-rich explanations of political, social, and environmental issues).

The Future: Diverse Global Orientations?

Despite the powerful forces pushing Oceania toward Asia, important factors still favor strong ties with Europe and North America. In spite of increasing trade links and recent efforts by China to expand diplomatic and cultural relations with Australia, both Australia and New Zealand remain staunch military allies of the United States. Over the years, both have participated in U.S.-led wars in Korea, Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq. In 2012, in an apparent effort to check the growing influence of the Chinese military in the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean, the Australian government gave the U.S. Marine Corps access to a large tract of land near Darwin (located in Australia’s Northern Territory). The United States and Australia also opened discussions regarding the use of the Cocos Islands (Australian possessions in the Indian Ocean) for reconnaissance purposes.

In some of the Pacific islands, strong links to Europe and North America are also upheld by continuing administrative control. In Micronesia, the United States governs Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands; in Polynesia, American Samoa is a U.S. territory. Just as the Hawaiian Islands are a U.S. state, the 120 islands of French Polynesia—including Tahiti and the rest of the Society Islands, the Marquesas Islands, and the Tuamotu Archipelago—are Overseas Lands of France. Any desire people in these possessions have for independence has not been sufficient to override the financial benefits of aid, subsidies, and investment money provided by France and the United States.

In 1989, the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperative (APEC), composed of 21 members (Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, China, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, Peru, the Philippines, Russia, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand, the United States, and Vietnam) was organized to enhance economic prosperity and strengthen the Asia–Pacific community. APEC is the only intergovernmental group in the world that operates on the basis of nonbinding commitments and open dialogue among all participants. Unlike the WTO or NAFTA or even the European Union (after which it is partially patterned), APEC does not oblige its members to participate in any treaties. Decisions made within APEC are reached by consensus (meaning discussions continue and agreements are adjusted until all consent) and commitments are undertaken on a voluntary basis. APEC’s member economies account for approximately 40 percent of the world’s population, just over 50 percent of global production, and more than 40 percent of global trade.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Geographic Insight 3Globalization and Development Globalization is reorienting Oceania (especially Australia and New Zealand) toward Asia as a major destination for exports and an increasing source of Oceania’s imports and tourists.

Geographic Insight 3Globalization and Development Globalization is reorienting Oceania (especially Australia and New Zealand) toward Asia as a major destination for exports and an increasing source of Oceania’s imports and tourists. Service industries are becoming the dominant income source for most of the region’s economies, although extractive industries remain important; subsistence is a crucial economic supplement.

Service industries are becoming the dominant income source for most of the region’s economies, although extractive industries remain important; subsistence is a crucial economic supplement. Tourism is a significant and growing part of the economies in Oceania, but it can produce stresses.

Tourism is a significant and growing part of the economies in Oceania, but it can produce stresses. Oceania is the center of a unique attempt (APEC) to forge international cooperation on food security, climate change, and energy-efficient transportation.

Oceania is the center of a unique attempt (APEC) to forge international cooperation on food security, climate change, and energy-efficient transportation.