1.8 Human and Cultural Geography

culture all the ideas, materials, and institutions that people have invented to use to live on Earth that are not directly part of our biological inheritance

Ethnicity, Culture, and Values

ethnic group a group of people who share a common ancestry and sense of common history, a set of beliefs, a way of life, a technology, and usually a common geographic location of origin

The Kurds in Southwest Asia are an example of the tenacity of this ethnic or cultural group identity. Long before the U.S. war in Iraq, the Kurds were asserting their right to create their own country in the territory where they have lived as nomadic herders since before the founding of Islam. Syria, Iraq, Iran, and Turkey now claim parts of the traditional Kurdish area. Many Kurds are now educated urban dwellers, living and working in modern settings in Turkey, Iraq, Iran, or even London and New York, yet they actively support the cause of establishing a Kurdish homeland. Although urban Kurds think of themselves as ethnic Kurds and are so regarded in the larger society, they do not follow the traditional Kurdish way of life. We could argue that these urban Kurds have a new identity within the Kurdish culture or ethnic group. Or they may be in a transcultural position, moving from one culture to another.

Another problem with the imprecision of the concept of culture is that it is often applied to a very large group that shares only the most general of characteristics. For example, one often hears the terms American culture, African American culture, or Asian culture. In each case, the group referred to is far too large to share more than a few broad characteristics.

multicultural society a society in which many culture groups live in close association

Values

Occasionally you will hear someone say, “After all is said and done, people are all alike,” or “People ultimately all want the same thing.” It is a heartwarming sentiment, but an oversimplification. True, we all want food, shelter, health, love, and acceptance; but culturally, people are not all alike, and that is one of the qualities that makes the study of geography interesting. We would be wise not to expect or even to want other people to be like us. It is often more fruitful to look for the reasons behind differences among people than to search hungrily for similarities. Cultural diversity has helped humans to be successful and adaptable animals. The various cultures serve as a bank of possible strategies for responding to the social and physical challenges faced by the human species. The reasons for differences in behavior from one culture to the next are usually complex, but they are often related to differences in values. Consider the following vignette that contrasts the values and norms (accepted patterns of behavior based on values) held by modern and urban individualistic cultures with those held by rural, community-oriented cultures.

VIGNETTE

One recent rainy afternoon, a beautiful 40-something Asian woman walked alone down a fashionable street in Honolulu, Hawaii. She wore high-heeled sandals, a flared skirt that showed off her long legs, and a cropped blouse that allowed a glimpse of her slim waistline. She carried a laptop case and a large fashionable handbag. Her long, shiny black hair was tied back. Everyone noticed and admired her because she exemplified an ideal Honolulu businesswoman: beautiful, self-assured, and rich enough to keep herself well-dressed.

In the village of this woman’s grandmother—whether it be in Japan, Korea, Taiwan, or rural Hawaii—the dress that exposed her body to open assessment and admiration by strangers of both sexes would signal that she lacked modesty. The fact that she walked alone down a public street—unaccompanied by her father, husband, or female relatives—might even indicate that she was not a respectable woman. That she at the advanced age of 40 was investing in her own good looks might be assessed as pathetic self-absorption. Thus a particular behavior may be admired when judged by one set of values and norms but may be considered questionable or even disreputable when judged by another. [Source: From Lydia Pulsipher’s field notes. For detailed source information, see Text Credit pages.]

If culture groups have different sets of values and standards, does that mean that there are no overarching human values or standards? This question increasingly worries geographers, who try to be sensitive both to the particularities of place and to larger issues of human rights. Those who lean too far toward appreciating difference could end up tacitly accepting inhumane behavior, such as the oppression of minorities or violence against women. Acceptance of difference does not preclude judgments of extreme customs or points of view. Nonetheless, although it is important to take a stand against cruelty of all sorts, deciding when and where to take that stand is rarely easy.

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Altruism

Recognizing all the ills that have emerged from racism and similar prejudices, we need not infer that human history has been marked primarily by conflict and exploitation or that these conditions are inevitable. Actually, humans have probably been so successful as a species because of a strong inclination toward altruism, the willingness to sacrifice one’s own well-being for the sake of others. It is probably our capacity for altruism that causes us such deep distress over the relatively infrequent occurrences of inhumane behavior.

Religion and Belief Systems

The religions of the world are formal and informal institutions that embody value systems. Most have roots deep in history, and many include a spiritual belief in a higher power (such as God, Yahweh, or Allah) as the underpinning for their value systems. Today religions often focus on reinterpreting age-old values for the modern world. Some formal religious institutions—such as Islam, Buddhism, and Christianity—proselytize; that is, they try to extend their influence by seeking converts. Others, such as Judaism and Hinduism, accept converts only reluctantly. Informal religions, often called belief systems, have no formal central doctrine and no firm policy on who may or may not be a practitioner. The fact that many people across the world combine informal religious beliefs with their more formal religious practices, of whatever persuasion, accounts for the very rich array of personal beliefs found on Earth today.

Religious beliefs are often reflected in the landscape. For example, settlement patterns often demonstrate the central role of religion in community life: village buildings may be grouped around a mosque, a temple, a synagogue, or a church, and the same can be said for urban neighborhoods. In some places, religious rivalry is a major feature of the landscape. Certain spaces may be clearly delineated for the use of one group or another, as in Northern Ireland’s Protestant and Catholic neighborhoods.

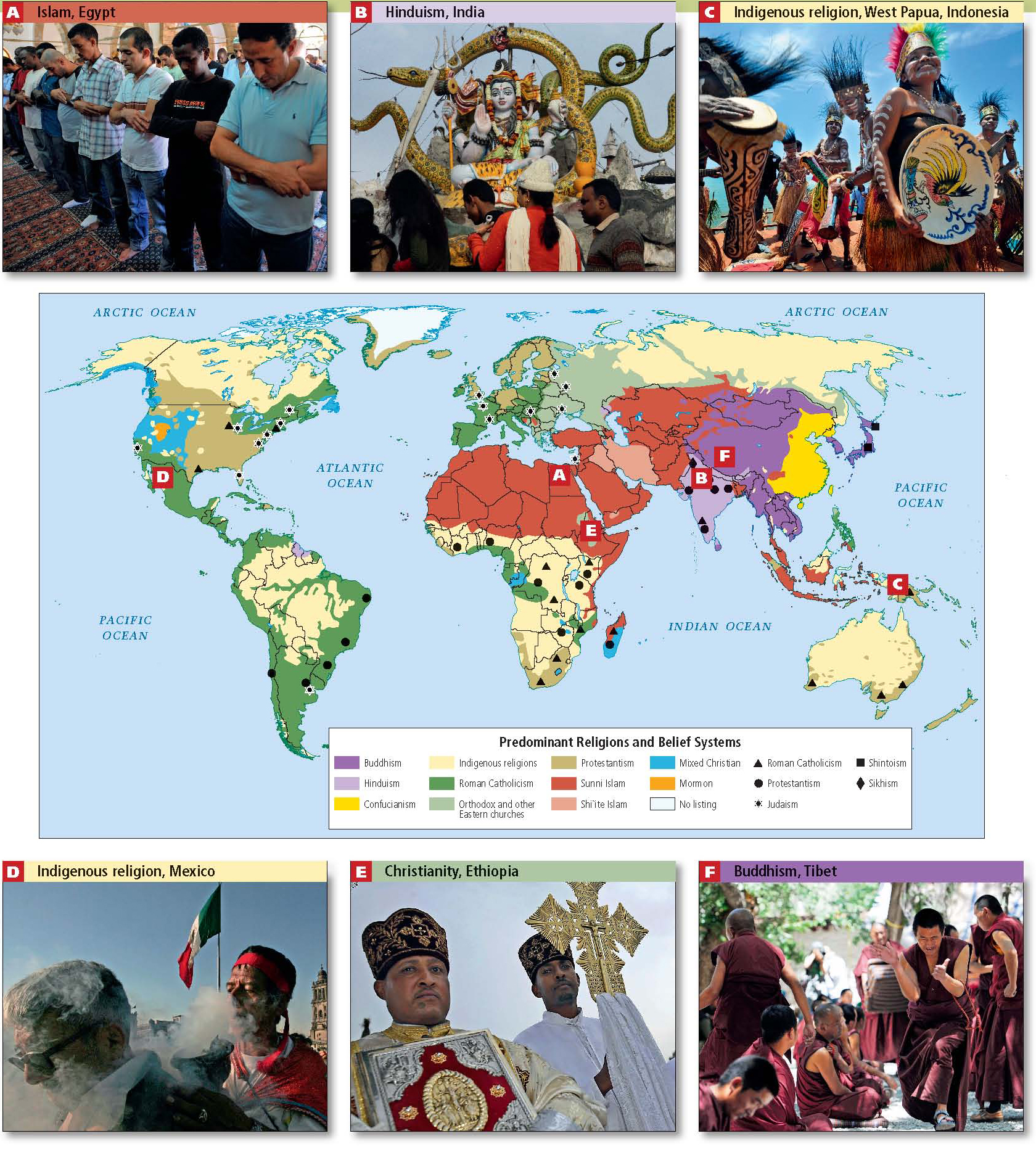

Religion has also been used to wield power. For example, during the era of European colonization, religion (Christianity) was a way to impose a change of attitude on conquered people. And the influence lingers. Figure 1.30A–F shows the distribution of the major religious traditions on Earth today; it demonstrates some of the religious consequences of colonization. Note, for instance, the distribution of Roman Catholicism in the parts of the Americas, Africa, and Southeast Asia, all places colonized by European Catholic countries.

Religion can also spread through trade contacts. In the seventh and eighth centuries, Islamic people used a combination of trade and political power (and less often, actual conquest) to extend their influence across North Africa, throughout Central Asia, and eventually into South and Southeast Asia (see Figure 6.14 map).

Language

Language is one of the most important criteria used in delineating cultural regions. The modern global pattern of languages reflects the complexities of human interaction and isolation over several hundred thousand years. Between 2500 and 3500 languages are spoken on Earth today, some by only a few dozen people in isolated places. Many languages have several dialects—regional variations in grammar, pronunciation, and vocabulary.

The geographic pattern of languages has continually shifted over time as people have interacted through trade and migration. The pattern changed most dramatically around 1500, when the languages of European colonists began to replace the languages of the people they conquered. For this reason, English, Spanish, Portuguese, or French are spoken in large patches of the Americas, Africa, Asia, and Oceania. Today, with increasing trade and instantaneous global communication, a few languages have become dominant. English is now the most important language of international trade, but Arabic, Spanish, Chinese, Hindi, and French are also widely used (see Figure 1.31). At the same time, other languages are becoming extinct because children no longer learn them within families.

Race

race a social or political construct that is based on apparent characteristics such as skin color, hair texture, and face and body shape, but that is of no biological significance

Some of the easily visible features of particular human groups evolved to help them adapt to environmental conditions. For example, biologists have shown that darker skin (containing a high proportion of protective melanin pigment) evolved in regions close to the equator, where sunlight is most intense (see Figure 1.32; see also Figure 1.27). All humans need the nutrient vitamin D, and sunlight striking the skin helps the body absorb vitamin D. Too much of the vitamin, however, can result in improper kidney functioning. Dark skin absorbs less vitamin D than light skin and thus would be a protective adaptation in equatorial zones. In higher latitudes, where the sun’s rays are more dispersed, light skin facilitates the sufficient absorption of vitamin D; darker-skinned people at these higher latitudes may need to supplement vitamin D to be sure they get enough, since D deficiencies can result in several health risks. Meanwhile, light-skinned people with little protective melanin in their skin—if they live in equatorial or high-intensity sunlit zones (parts of Australia, for example)—will need to protect against too much vitamin D, serious sunburn, and skin cancer. Similar correlations have been observed between skin color, sunlight, and another essential vitamin, folate, which if deficient can result in birth defects.

Over time, race has acquired enormous social and political significance as humans from different parts of the world have encountered each other in situations of unequal power. Racism—the belief that genetic factors, usually visually apparent ones such as skin color, are a primary determinant of human abilities and even cultural traits—has often been invoked to justify the enslavement of particular groups, or confiscation of their land and resources. Racism is insidious and hard to stamp out, in part because in the eyes of many, of all skin tones, whiteness is considered the “normal condition,” while all other colors are simply nonwhite. Race and its implications in North America will be covered in Chapter 2, and the topic will be discussed in several other world regions as well (see also a TED—Technology, Entertainment, and Design—talk by anthropologist Nina Jablonski, at http://tinyurl.com/l7wg7m).

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Human geographers are interested in the economic, social, and cultural practices of a people and in the spatial patterns these practices create.

Human geographers are interested in the economic, social, and cultural practices of a people and in the spatial patterns these practices create. Cultural geography seeks to understand human variability on Earth through a variety of lenses: culture and ethnicity, religion, language, and race.

Cultural geography seeks to understand human variability on Earth through a variety of lenses: culture and ethnicity, religion, language, and race. Race is biologically meaningless, yet it has acquired enormous social and political significance. Evolutionary science and the study of social history can aid in dispelling racist misconceptions.

Race is biologically meaningless, yet it has acquired enormous social and political significance. Evolutionary science and the study of social history can aid in dispelling racist misconceptions.