East Africa

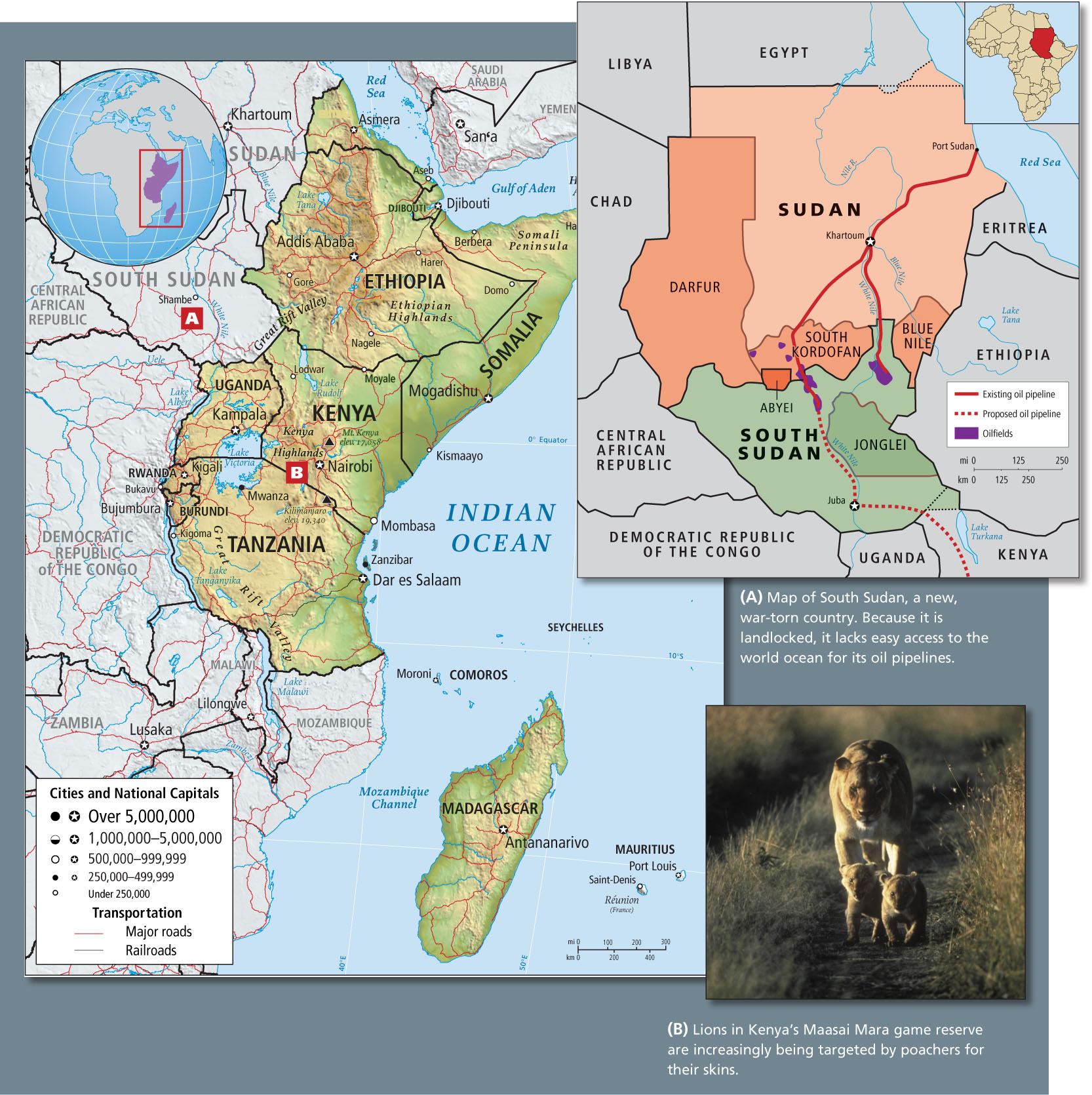

The subregion of East Africa (Figure 7.36) occupies the Horn of Africa, which reaches along the southern shore of the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden, and includes the countries of Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia, and the newly independent country of South Sudan. To the south of the Horn, the subregion includes the coastal countries of Kenya and Tanzania; the interior highland countries of Uganda, Rwanda, and Burundi in the Great Rift Valley; and the islands of Madagascar, Comoros, Seychelles, Mauritius, and Réunion in the Indian Ocean across the Mozambique Channel.

Across the subregion, the relatively dry coastal zones contrast with the more moist interior uplands; but further to the west, the drying effects of the Sahara affect South Sudan, Uganda, and western Tanzania. A vital and productive farming economy has long existed in the interior uplands; across the region today, nearly 80 percent of the population makes a living from farming. A service economy is beginning to grow in urban areas and tourism zones along the coast, in Madagascar, and around the national parks of Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania (see Figure 7.36B). Industry is only beginning to be developed, and is found primarily in Kenya and Tanzania. On the coast, where port cities have a thousand-year history of trade across the Arabian Sea and Indian Ocean, trade-related services are central to economies.

Conflict in the Horn of Africa

Africa’s ability to support its people is being tested in East Africa, where the growing population and the related increase in consumption are straining the region’s carrying capacity. The entire Horn of Africa has suffered periodic famines since the mid-1980s, caused by governments and political officials who have manipulated innumerable situations for personal gain, resulting in ineffective responses to naturally occurring droughts. The result in Somalia, Ethiopia, and now South Sudan, often referred to as failing states, has been an environment of chaos and lawlessness for ordinary citizens.

Newly Independent South Sudan

South Sudan occupies what was once the southern third of the oil-rich country of Sudan (covered in Chapter 6). The south of Sudan, which has a population mostly made up of darker-skinned Christians who have sub-Saharan origins, has always been culturally quite different from the more Arabic north. South Sudan was often handled roughly by the north and dismissed as unimportant and out of touch, although the south is where two-thirds of Sudan’s oil is located. After a long and bloody struggle over the oil, South Sudan won independence in 2011, but the border between the two countries is not yet agreed upon; South Sudan is landlocked and thus has no easy way to get its oil to the world market. The possession of the oil (and the accompanying right to use the oil) remains in contention. Private oil companies based in China and Malaysia have brokered a settlement with the intention of acquiring the oil and getting it to a Red Sea port in pipelines through Sudan.

The Role of Militant Islamists in the Horn

Militant Islamists—most prominently, Al Shabaab—have attempted to impose order and conformity in the Horn of Africa, but their rigid rules, especially those regarding women, have been oppressive. Furthermore, their rise has led to worry on the part of other nations that a new nexus of Islamist terrorism is evolving. In 1993, the United States, in an effort to quell the conflict, stepped in on the side of corrupt warlords. This resulted in the debacle in and around Mogadishu, Somalia, depicted in the 2001 film Black Hawk Down. The United States withdrew, and although conflict flared again in 2006 and 2009, by 2012, when Somalia held its first parliamentary elections in two decades, Al Shabaab was far less influential.

East African Piracy and Its Root Causes

In 2008, the world became aware of the dangers to global shipping posed by a band of pirates from Somalia. During that year, 40 commercial ships from multiple nations (Denmark, Japan, Ukraine, the United States, North Korea, Taiwan, India, China, and others) were attacked or seized. When the privately owned American ship Alabama was boarded in April 2009 and the captain taken prisoner, a serious discussion began on the root causes of the piracy phenomenon and how to stop it.

The article, “The Two Piracies in Somalia: Why the World Ignores the Other,” by Mohamed Abshir Waldo of Mombasa, Kenya (2009), is enlightening. Waldo explains that the long conflict in Somalia, which forced many farmers and herders into refugee camps and some into fishing for a living, was a big factor in the turn to piracy. But a more proximate cause was “fishing encroachment” by large commercial fishing fleets (from Italy, France, Spain, Greece, Russia, the Arabian Peninsula, and the Far East), in which traditional small-boat Somali fishers were displaced and harassed. Coastal villagers in Somalia also accused the foreign fishing fleets of purposefully polluting the seabeds and of violently seizing their boats. Western warships, providing security to the large commercial fishing fleets, further harassed Somali fishers. Eventually the fishers joined with unidentified criminal groups in East Africa to create this new “entrepreneurial” solution of high-seas piracy. An interactive BBC Web site, available at http://tinyurl.com/c5pmdr5, provides a map and helpful background information on piracy in East Africa.

Interior Valleys and Uplands

East Africa’s interior is dominated by the Great Rift Valley, an irregular series of tectonic rifts that curve inland from the Red Sea and extend southwest through Ethiopia and into the highland Great Lakes region where Lake Victoria forms the headwaters of the White Nile. The rifts then bend around the western edges of the subregion and extend into Mozambique to the south of the subregion (see Figure 7.36). The Great Rift Valley, which contains numerous archaeological sites that have shed light on the early evolution of humans and other large mammals, is today covered primarily with temperate and tropical savanna, although patches of forest remain on the high slopes and in southwestern Tanzania. In Ethiopia, deep river valleys, including that which holds the headwaters of the Blue Nile, drain the semiarid highlands. Rain falls during the summer, and conditions vary with elevation. For most rural people who make a living by herding cattle, finding water is always a concern, but in the moister central uplands of Ethiopia and Kenya and in the woodlands of southern Tanzania, herding and cultivation are combined in mixed farming. Animal manure is used to fertilize a wide variety of crops that are closely adapted to particularly fragile environments, and pastures and fields are rotated systematically. These ancient and specialized mixed-agriculture systems were ignored and disdained by European colonizers, and agronomists have only recently begun to appreciate the precision of African upland mixed agriculture, which is now threatened by civil disorder, development schemes, and population pressure.

Coastal Lowlands

To the east and south of the Ethiopian highlands is a broad, arid apron that descends to the Gulf of Aden and the Indian Ocean. Along the coasts of the Horn of Africa are large stretches of sand and salt deserts, a few rivers, and a few port cities. In Somalia, which occupies the low, arid coastal territory in the Horn, people eke out a meager living through cultivation around oases and herding in the dry grasslands. Somalia’s 8 million people, virtually all Muslim and ethnically Somali, are aligned in six principal clans. Islamic fundamentalists, clan-based warlords, and political adventurers have engaged in a violent rivalry for power over the last few decades. The resulting turmoil has driven many cultivators from their lands and has blocked access to some lands that are crucial to the food production system, so the land that is still available is being overused. Thus it is primarily politics, not rapid population growth, that has increased pressure on arable land in all countries of the Horn of Africa. Nonetheless, at present rates of growth, populations in the Horn are expected to double and even triple by 2050, and conditions will make it difficult to accommodate the increase.

East Africa’s shores from southern Somalia southward (known regionally as the Swahili Coast) have long attracted traders from around the Indian Ocean—from China, Indonesia, Malaysia, India, Persia (Iran), Arabia, and elsewhere in Africa. The result has been a grand blending of peoples, cultures, languages, plants, and animals. In the sixth century, Arab traders brought Islam to East Africa, where it remains an important influence in the north and along the coast. Traders, speaking the lingua franca of Swahili, established networks that linked the coast with the interior. These networks penetrated deeply into the farming and herding areas of the savanna and into the semifeudal cultures of the highland lake country. Today, trade across the Indian Ocean continues. Arab countries are East Africa’s most important trading partners, but Asia, China, India, and Japan are increasingly important to East African trade; trade with Indonesia and Malaysia is also increasing. East Africa, which needs more industrialization, exports mostly agricultural products (live animals, hides, bananas, coffee, cashews, processed food, tobacco, and cotton) and imports machinery, transportation and communication equipment, industrial raw materials, and consumer goods.

Contested Space in Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania

Kenya and Tanzania are modestly industrialized countries in East Africa that remain largely dependent on agricultural exports, like cacao, and some finished products: tea, coffee, beer, horticultural products, and processed food, as well as cement and petroleum products. Both countries are regional hubs of trade, yet both are among the poorest countries in the world.

Beginning in ancient times, traders dealt in slaves, ivory, and rare animals, items that can no longer be legally traded. British colonists took over in the early nineteenth century when the old trading economy was failing. The British relocated native highland farmers in Kenya, such as the Kikuyu, to make way for coffee plantations; in the savannas of Kenya and Tanzania, they displaced pastoralists, such as the Masai. Some of the lands of the Masai became game reserves designed to protect the savanna wildlife for the use of European hunters and tourists.

National Parks as Protectors of Africa’s Wild Heritage

Today, the former colonial game reserves of Kenya and Tanzania are among the finest national parks in Africa, offering protection to wild elephants, giraffes, zebras, and lions, as well as to many less spectacular but no less significant species (see Figure 7.36B). Tourism, mostly in the form of visits to these parks, accounts for 20 percent of foreign exchange earnings; in 2013, it brought both Kenya and Tanzania approximately $1.13 billion. The future of the parks is precarious, however, because of competing demands for the land by herders and cultivators and the indigenous tendency to view wild animals as a useful, consumable resource (bushmeat, ivory). In Kenya, a living elephant is worth close to U.S.$15,000 a year in income from tourists who come to see it. Nonetheless, some still view hunting elephants for their ivory as a profitable activity, even though a hunter earns no more than $1000 per dead animal.

A more sinister, very recent development, reported by Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Jeffrey Gettleman, is the organized slaughter of elephants in the zone where Congo, South Sudan, Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania come together. Thousands have been killed, their ivory stolen, and their bodies left to rot by poachers who are apparently using helicopters. Gettleman reported that the ivory trade is fueled largely by Chinese demand, but the perpetrators involve military rogues from all the countries in this zone, as well as the Janjaweed in Darfur and Al Shabaab in Somalia.

Agriculture and Parks Vie for Land and Water

After Kenya’s independence from Britain in the early 1960s, government policies resettled African farmers on highland plantations formerly owned by Europeans, giving the country a strong base in export agriculture through the production of coffee, tea, sugarcane, corn, and sisal. Nomadic pastoralists fared less well than farmers because national parks were established on their lands and park managers, unfamiliar with local ecology, inadvertently encouraged the spread of tsetse fly infestations to the local pastoralist herds. The pastoralists and cultivators also vie for scarce water—the herders need regular sources of water for their animals, while the cultivators are increasingly irrigating their crops. Taking note of income from export agriculture, the government has sided with the farmers, even to the point of policing from armed helicopters the water gathering by nomadic herders.

In both Kenya and Tanzania, dependence on export agriculture has put both livelihoods and valuable national parks at risk. Rapid population growth since the mid-twentieth century is part of the problem. In 1946, Kenya had just 5 million people; by 2012, it had 43 million. In the past, this primarily arid land could adequately support relatively small populations when managed according to traditional herding and subsistence cultivation practices. Today, the land’s carrying capacity is severely stressed because population pressure is forcing farmers to plow and herders to overgraze wildland buffer zones surrounding the parks. Hungry people have begun to poach park animals for food, and there is now a large underground trade in bushmeat and ivory.

The Islands

Madagascar, lying across the Mozambique Channel from East Africa (see the Figure 7.36 map), is the fourth-largest island in the world; only Greenland, New Guinea, and Borneo are larger. Its unique plant and animal life is the result of diffusion (transmission by natural or cultural processes) from mainland Africa and Asia and subsequent evolution in isolation on the island. Although the island has undergone much change over the last few centuries, it remains an amazing evolutionary time capsule that is highly prized by biologists. They debate the exact features of the natural dispersal and evolutionary processes, and the role played by human occupants who came in ancient times from Africa and other places around the Indian Ocean, including Southeast Asia. Madagascar is increasingly attractive to tourists and developers, and is greatly threatened by environmental degradation (Figure 7.37).

The other East African island nations—the Comoros, the Seychelles, and Mauritius—are much smaller and less physically complex than Madagascar. All of the islands have a cosmopolitan ethnic makeup, the result of thousands of years of trade across the Mozambique Channel and the Indian Ocean. Further cultural mixing in the islands took place during European (primarily French and British) colonization. During the colonial era, these islands supported large European-owned plantations worked by laborers brought in from Asia and the African mainland. More recently, tourism has been added to the economic and biological diffusion mix. Most visitors come from the African mainland, from Asian countries surrounding the Indian Ocean, and from Europe.

Madagascar, with 22 million people, half of whom live on less than $1 a day, underwent IMF structural adjustment policies in the 1990s that failed to alleviate poverty. The island’s political leaders tend to be wealthy businessmen with little sense of the biological treasure that Madagascar is or of the necessity to address poverty and social welfare issues. In 2009, Andry Rajoelina—a former disc jockey, now a media magnate—staged a coup, with the aid of the military, against the democratically elected government that had been making progress on ecological and development fronts. His coup was not accepted, and 7 months of bloody fighting left more than 100 dead and halved tourism arrivals. In August 2009, a power-sharing agreement was reached. Elections, originally scheduled for 2011, were postponed until 2013.

THINGS TO REMEMBER

A physically diverse subregion, East Africa extends south from Eritrea to Tanzania on Africa’s east coast and includes the off-coast islands in the Indian Ocean.

A physically diverse subregion, East Africa extends south from Eritrea to Tanzania on Africa’s east coast and includes the off-coast islands in the Indian Ocean. The entire Horn of Africa has suffered periodic famines since the mid-1980s, caused by governments and political officials who have manipulated innumerable situations for personal gain, resulting in ineffective responses to naturally occurring droughts. South Sudan, a new country, has begun life with multiple challenges.

The entire Horn of Africa has suffered periodic famines since the mid-1980s, caused by governments and political officials who have manipulated innumerable situations for personal gain, resulting in ineffective responses to naturally occurring droughts. South Sudan, a new country, has begun life with multiple challenges. The former colonial game reserves of Kenya and Tanzania are among the finest national parks in Africa, offering protection to wild elephants, giraffes, zebras, lions, and many less spectacular but no less significant species. The rapid growth of the human population is resulting in competition over land use in both countries. Also, high-tech poaching, especially of elephants, is escalating.

The former colonial game reserves of Kenya and Tanzania are among the finest national parks in Africa, offering protection to wild elephants, giraffes, zebras, lions, and many less spectacular but no less significant species. The rapid growth of the human population is resulting in competition over land use in both countries. Also, high-tech poaching, especially of elephants, is escalating. The islands of East Africa have a cosmopolitan ethnic makeup, the result of thousands of years of trade across the Mozambique Channel and the Indian Ocean.

The islands of East Africa have a cosmopolitan ethnic makeup, the result of thousands of years of trade across the Mozambique Channel and the Indian Ocean.