2.4 HUMAN GEOGRAPHY

HUMAN PATTERNS OVER TIME

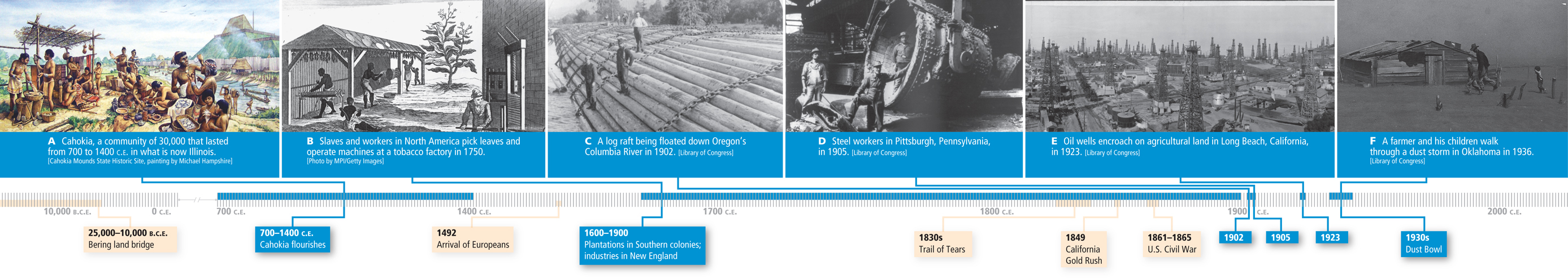

In prehistoric times, humans came from Eurasia via Alaska, dispersing to the south and east. Beginning in the 1600s, waves of European immigrants and enslaved Africans spread over the continent, primarily from east to west. Today, immigrants are coming mostly from all of Asia and from Middle and South America, arriving mainly in the Southwest and West, where immigrant populations are at their most concentrated. In addition, internal migration is still a defining characteristic of life for most North Americans, who are among the world’s most mobile people. The average North American moves nearly 12 times in a lifetime.

The Peopling of North America

Recent evidence suggests that humans first came to North America from northeastern Asia at least 25,000 years ago and perhaps earlier, most arriving during an ice age. At that time, the global climate was cooler, polar ice caps were thicker, and sea levels were lower. The Bering land bridge, a huge, low landmass more than 1000 miles (1600 kilometers) wide, connected Siberia to Alaska. Bands of hunters crossed by foot or small boats into Alaska and traveled down the west coast of North America.

The Original Settling of North America By 15,000 years ago, humans had reached nearly to the tip of South America and had moved deep into that continent. By 10,000 years ago, global temperatures began to rise. As the ice caps melted, sea levels rose and the Bering land bridge was submerged beneath the sea.

Over thousands of years, the people settling in the Americas domesticated plants, created paths and roads, cleared forests, built permanent shelters, and sometimes created elaborate social systems. About 3000 years ago, corn was introduced from Mexico (into what is now the southwestern U.S. desert), as were other Mexican domesticated crops, particularly squash and beans. Such food crops are thought to have been closely linked to settled life and to North America’s prehistoric population growth.

These foods provided surpluses that allowed some community members to engage in activities other than agriculture, hunting, and gathering, making possible large, city-

THINKING GEOGRAPHICALLY

Use the Visual History above to answer these questions.

Scroll to see the full graphic.

Question 2.10

A How did food crops such as corn, beans, and squash influence the development of settlements like Cahokia?

Question 2.11

B Why did the plantation system inhibit the establishment of roads, communication networks, and small enterprises that could have boosted other forms of economic activity in the Southern colonies?

Question 2.12

C What features of the economy of the Pacific Northwest today might surprise these men?

Question 2.13

D How did the steel industry stimulate development in the “economic core” of North America?

Question 2.14

E What is the evidence of economic diversification in this photo?

Question 2.15

F What were the causes of the Dust Bowl?

The Arrival of the Europeans North America was completely transformed by the sweeping occupation of the continent by Europeans. In the sixteenth century, Italian, Portuguese, and English explorers came ashore along the Eastern Seaboard of North America, and the Spanish explorer Hernando De Soto made his way from Florida deep into the heartland of the continent in the 1540s. In the early seventeenth century, the British established colonies along the Atlantic coast in what is now Virginia (1607) and Massachusetts (1620). The Dutch explored the Atlantic Seaboard looking for trading opportunities, and the French explored the northern interior of the continent, entering via the St. Lawrence River. Assisted by enslaved Africans, colonists and settlers from northern Europe built villages, towns, port cities, and plantations along the eastern coast over the next two centuries. By the mid-

Disease, Technology, and Native Americans The rapid expansion of European settlement was facilitated by the vulnerability of Native American populations to European diseases. Having been isolated from the rest of the world for many years, Native Americans had no immunity to diseases such as measles and smallpox. Transmitted by Europeans and Africans who had built up immunity to them, these diseases killed up to 90 percent of Native Americans within the first 100 years of contact. It is now thought that diseases spread by early expeditions, such as De Soto’s into Florida, Georgia, Tennessee, and Arkansas, so decimated populations in the North American interior that fields and villages were abandoned, the forest grew back, and later explorers erroneously assumed the land had never been occupied.

Technologically advanced European weapons, trained dogs, and horses also took a large toll. Often the Native Americans had only bows and arrows. Some Native Americans in the Southwest acquired horses from the Spanish and learned to use them in warfare against the Europeans, but their other technologies could not compete. Numbers reveal the devastating effect of European settlement on Native American populations. Roughly 18 million Native Americans lived in North America in 1492. By 1542, after just a few Spanish expeditions, only half that number survived. By 1907, slightly more than 400,000, or a mere 2 percent, remained.

The European Transformation

European settlement erased many of the landscapes familiar to Native Americans and imposed new ones that fit the varied physical and cultural desires of the new occupants.

The Southern Settlements European settlement of eastern North America began with the Spanish in Florida in the mid-

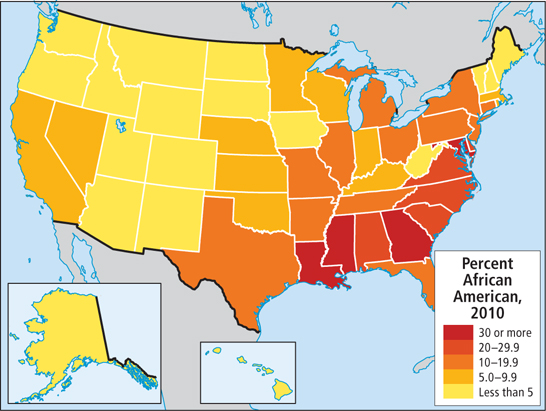

To secure a large, stable labor force, Europeans brought enslaved Africans into North America beginning in 1619. Within 50 years, enslaved Africans were the dominant labor force on some of the larger Southern plantations (see Figure 2.9B). By the start of the Civil War in 1861, enslaved people made up about one-

The plantation system consolidated wealth in the hands of a small class of landowners who made up just 12 percent of Southerners in 1860. Planter elites kept taxes low and invested money from their exported crops in Europe or the more prosperous northern colonies, instead of in infrastructure at home. As a result, the road, rail, communication networks, and other facilities necessary for further economic growth in the South were rarely built.

infrastructure road, rail, and communication networks and other facilities necessary for economic activity

More than half of Southerners were poor white farmers. Both they and the general slave population lived simply and their meager consumption did not provide much demand for goods. Because of this, there were few market towns and almost no industries. Plantations tended to import from Europe and the northern United States whatever they couldn’t produce for themselves. So instead of generating a multiplier effect, enabling local enterprises like small shops, garment making, small restaurants and bars, manufacturing, and transportation and repair services to expand as a result of “spinoff” from the main industries they serve, economic growth was much slower in the South.

The inability of the federal government to reconcile the different needs of the agricultural export–

The Northern Settlements Throughout the seventeenth century, relatively poor subsistence farming communities dominated the colonies of New England and southeastern Canada. There were no plantations and few slaves, and not many cash crops were exported. What exports there were consisted of raw materials like timber, animal pelts, and fish from the Grand Banks off Newfoundland and the coast of Maine. Generally, farmers lived in interdependent communities that prized education, ingenuity, self-

By the late 1600s, New England was implementing ideas and technology from Europe that led to the first industries. By the 1700s, diverse industries were supplying markets in North America and the Caribbean with metal products, pottery, glass, and textiles. By the early 1800s, southern New England, especially the region around Boston, became the center of manufacturing in North America. It drew largely on young male and female immigrant labor from French Canada and Europe.

The Mid-

economic core the dominant economic region within a larger region

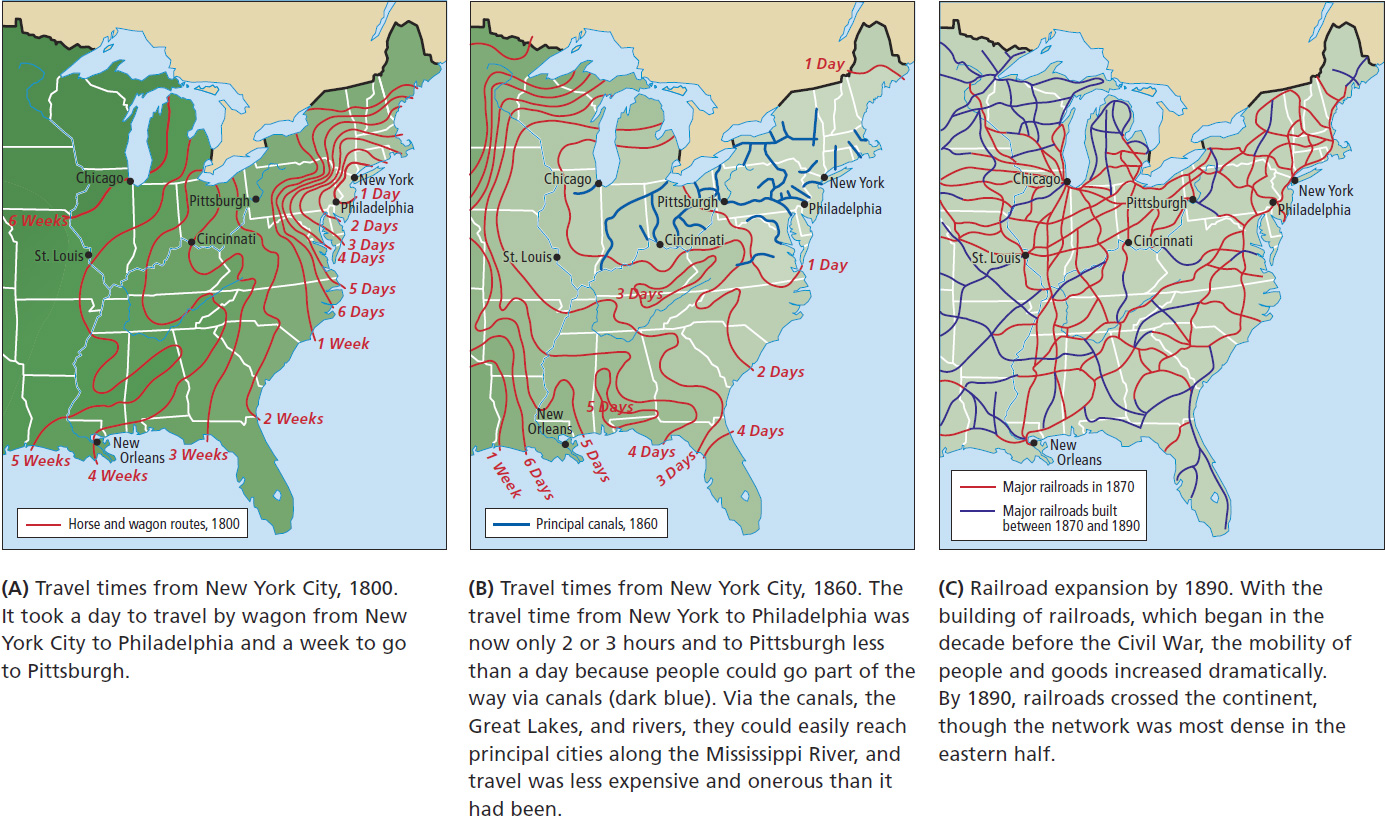

In the early nineteenth century, both agriculture and manufacturing grew and diversified, drawing immigrants from much of northwestern Europe. As farmers became more successful, they bought mechanized equipment, appliances, and consumer goods made in nearby cities. By the mid-

By the early twentieth century, the economic core stretched from the Atlantic to St. Louis on the Mississippi (including many small industrial cities along the river, plus Chicago and Milwaukee), and from Ottawa to Washington, DC. It dominated North America economically and politically well into the middle of the twentieth century. Most other areas produced food and raw materials for the core’s markets and depended on the core’s factories for manufactured goods.

Expansion West of the Mississippi and Great Lakes

The east-

The Great Plains Much of the land west of the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River was dry grassland or prairie. The soil usually proved very productive in wet years, and the area became known as North America’s breadbasket. But the naturally arid character of this land eventually created an ecological disaster for Great Plains farmers. In the 1930s, after 10 especially dry years, a series of devastating dust storms blew away topsoil by the ton. This hardship was made worse by the widespread economic depression of the 1930s. Many Great Plains farm families packed up what they could and left what became known as the Dust Bowl (see Figure 2.9F), heading west to California and other states on the Pacific coast.

The Mountain West and Pacific Coast Some Europeans, alerted to the possibilities farther west, skipped over the Great Plains entirely. By the 1840s, they were coming to the valleys of the Rocky Mountains, to the Great Basin, and to the well-

The extension of railroads across the continent in the nineteenth century facilitated the transportation of manufactured goods to the West as well as raw materials and eventually fresh produce to the East. Today, the coastal areas of this region, often called the Pacific Northwest, have thriving, diverse, high-

The Southwest People from the Spanish colony of Mexico first colonized the Southwest in the late 1500s. Their settlements were sparse. As immigrants from the United States expanded into the region, drawn by the cattle-

By the twentieth century, a vibrant agricultural economy had developed in central and southern California, supported by massive government-

European Settlement and Native Americans

As settlement relentlessly expanded west, Native Americans (called First Nations people in Canada) who had survived early encounters with Europeans and were living in the eastern part of the continent occupied land that European newcomers wished to use. During the 1800s, almost all the surviving Native Americans were killed in innumerable skirmishes with European newcomers, absorbed into the societies of the Europeans (through intermarriage and acculturation), or forcibly relocated west to relatively small reservations with few resources. The largest relocation, in the 1830s, involved the Choctaw, Seminole, Creek, Chickasaw, and Cherokee of the southeastern states. These people had already adopted many European methods of farming, building, education, government, and religion. Nevertheless, they were rounded up by the U.S. Army and marched to Oklahoma, along a route that became known as the Trail of Tears because of the more than 4000 Native Americans who died along the way.

As Europeans occupied the Great Plains and prairies, many of the reservations were further shrunk or relocated onto even less desirable land. Today, reservations cover just over 2 percent of the land area of the United States.

In Canada the picture is somewhat different. Reservations now cover 20 percent of Canada, mostly because of the creation of the Nunavut Territory (now known simply as Nunavut) in 1999 in the far north and the ceding of Northwest Territory land to the Tłįchǫ First Nation (also known as the Dogrib) in 2003 (see the Figure 2.1 map). These Canadian First Nations stand out as having won the right to legal control of their lands. In contrast to the United States, it had been unusual for native groups in Canada to have legal control of their territories.

After centuries of mistreatment, many Native American and First Nations people still live in poverty and, as in all communities under severe stress, rates of alcohol and drug addiction and violence are high. However, in recent decades some tribes have found avenues to greater affluence on the reservations and territories by establishing manufacturing industries; developing fossil fuel, uranium, and other mineral deposits under their lands; or opening gambling casinos. One measure of this economic resurgence is population growth. Expanding from a low of 400,000 in 1907, the Native American population, at less than 2 percent of the total population, stood at approximately 6 million in 2010 in the United States. In Canada, First Nations people number over 1.2 million, or 3.8 percent of the population.

The Changing Regional Composition of North America

The regions of European-

THINGS TO REMEMBER

Recent evidence suggests that humans first came to North America from northeastern Asia at least 25,000 years ago and perhaps earlier, most arriving during an ice age.

By the late 1600s, New England was implementing ideas and technology from Europe and developing some of the first industries in North America.

By the early twentieth century, North America’s economic core was well established. Stretching from the Atlantic Ocean to St. Louis, Chicago, and Milwaukee, and from Ottawa to Washington, DC, it dominated North America economically and politically well into the middle of the twentieth century.

The push to settle the Great Plains, the Mountain West, and the Pacific Coast attracted many immigrants, from both Mexico and Europe, interested in farming, mining, and cattle raising.

In 1492, roughly 18 million Native American and First Nations people lived in North America. By 1542, after only a few Spanish expeditions, there were half that many. By 1907, only about 2 percent of the original population remained; however, by 2010, the Native American and First Nations populations had partially rebounded to approximately 7 million.