2.6 POWER AND POLITICS

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 3

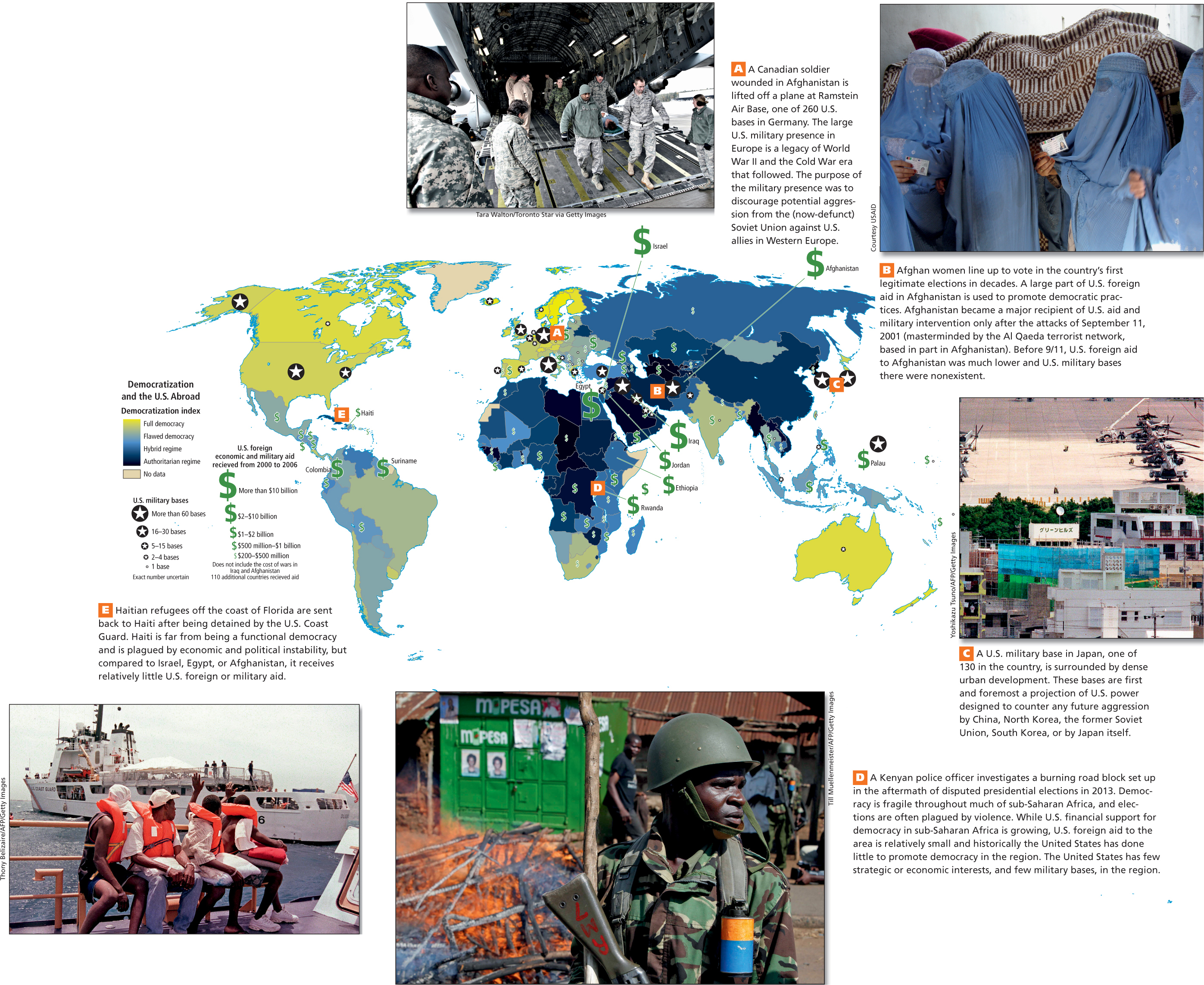

Power and Politics: North America has relatively high levels of political freedom, though in recent decades many of its residents have become disillusioned with the political process for a variety of reasons. While Canada plays a relatively modest political role abroad, the United States has enormous influence on the global political order, although its status as the world’s predominant “superpower” is increasingly being challenged.

The Expansion of Political Freedoms in the United States and Canada

North Americans’ relatively high levels of political freedom are part of a long-

The ways in which candidates for elected office are selected has also opened up in both countries. In the past, a few political insiders selected the candidates that they wanted to run for a particular office. Starting in the 1920s in the United States, candidates for office began to be selected via primaries, which are elections that determine who a political party will nominate to run as their candidate for a particular office. For example, in 2008, Barack Obama was chosen to be the Democratic Party’s candidate for the office of president of the United States only after he won a series of primaries held in states throughout the country in which he and a number of other candidates ran. After he won the primary, Obama went on to run in the general election, which he also won. Primaries have only recently been adopted in Canada, in part because they are a much more expensive way to choose candidates.

Political Disillusionment While the overall trajectory has been toward more openness in the political process, giving individuals more influence over their governance, there has been a general disillusionment with politics in both the United States and Canada. Evidence of this can be seen in lower voter turnout—the percentage of people who decide to cast a vote in an election. Voter turnout has been declining since the 1960s, with the United States having a generally lower voter turnout than Canada: 57.5 percent of voting-

One possible reason for the lower turnout in the United States is the frustration created by the role of money in politics. A potential candidate for a major office in the United States must now spend millions or, in the case of the office of the U.S. president, more than a billion dollars, to win an election. This cost is a major barrier to people who want to enter into politics, as only those able to raise large amounts of money have any chance to win. Expensive elections also mean that successful candidates have to spend more of their time raising money in order to be reelected and less time doing their job representing the people who elected them. As a result, politicians tend to focus on wealthy people and corporations who can make the donations that will help them get reelected. This trend in politics runs counter to the ideal that a person’s income should not determine their ability to influence their government. Canada’s somewhat higher voter turnout rates may be the result of Canadian laws that regulate the amount of money candidates and their political parties can spend on elections.

Other explanations of the disillusionment with the political process focus on the role of television, which gained popularity in the 1960s, at about the same time that voter turnout started to decline. More time spent watching television is correlated with lower levels of community involvement and less participation in the political process.

Debt and Politics in the United States

There is much worry and political maneuvering in the United States surrounding the national debt. The debt consists of the money the United States borrows by issuing treasury securities to cover the expenses it has that exceed income from taxes and other revenues. There are two components to the U.S. debt: debt held by the public, including that held by private investors, the Federal Reserve System, and foreign, state, and local governments ($12.3 trillion as of December 2013); and debt held in accounts administered by the federal government, such as that borrowed from the Social Security Trust Fund ($4.9 trillion as of December 2013).

To whom does the United States owe its debt? About 70 percent of the total debt is owed to U.S. citizens who own treasury securities, and to various federal government entities, like the Social Security Trust Fund. About 29 percent is owed to foreign governments (8 percent to China, 5 percent to Japan, 2 percent to the United Kingdom, and smaller amounts to Brazil, Taiwan, and Hong Kong).

Proposed solutions highlight the differences between the two major political parties in the United States. Most Republicans believe that the debt is dangerous and needs to be reduced immediately by drastically reducing government spending, especially on social services such as the Affordable Health Care Act (often called “Obamacare”) and various kinds of aid to the poor. Many Democrats hold that some government spending, especially military spending and subsidies to large corporations, should be cut. But they also argue that new revenues should be raised by taxing the very rich. These differences between the two major political parties show up repeatedly in the United States, as the government’s ability to raise revenue via taxation and the ways it spends this revenue are central to almost every major political issue.

The United States and Canada Abroad

The United States and Canada have dramatically different roles in the global geopolitical order. The United States is recognized as the most powerful country in the world, with the world’s largest economy and a military budget that year to year is larger than those of the next largest 12 or 13 countries combined. While the promotion of democracy and political freedoms is an official goal of U.S. foreign policy, in practice, the United States tends to focus its activities abroad more on its own economic and strategic military interests, which are often linked. This can be seen, for example, in the recent U.S. war in Iraq, which numerous planners of the war within the Bush Administration now acknowledge was motivated more by a desire to control access to Iraq’s lucrative oil reserves than to bring democracy to Iraq (Figure 2.17).

THINKING GEOGRAPHICALLY

Use the Photo Essay above to answer these questions.

Question 2.16

A What economic interests does the United States have in Europe?

Question 2.17

B What strategic and economic interests make it unlikely that the United States will withdraw completely from Afghanistan and Iraq in the near future?

Question 2.18

D What has kept U.S. economic interests in Africa at a low level relative to those in other regions?

Question 2.19

E What has kept U.S. economic interests in Haiti at a low level relative to those in other countries?

U.S. economic and strategic interests are reflected in the global distribution of its military bases and its spending on aid to foreign governments. Three main concentrations of bases and spending, where the United States has for years had strong strategic and economic interests, can be seen on the map in Figure 2.17 in (1) Europe; (2) North Africa and Southwest Asia (especially Egypt, Israel, Iraq, Jordan), and Afghanistan and Pakistan in South Asia; and (3) island and peninsular East Asia. The first and third concentrations of bases and spending (those in Europe and East Asia) relate to strategic and economic interests dating from World War II that have remained relevant due to the Cold War (see Chapter 1), the subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union (see Chapter 5), the continued large volume of trade between the United States and Europe, and the rapid growth of U.S. trade with East Asia since the opening up of China (see Chapter 9; see also Figure 2.17C). The second concentration relates directly to U.S. interests in Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Israel, and Egypt, and the oil and mineral resources of South and Southwest Asia in general.

The map in Figure 2.17 also shows that there are many places where the United States does not have many bases and where spending on foreign aid is at low or moderate levels. These are generally places where the United States has fewer strategic and economic interests. In part because of the poverty and political instability of sub-

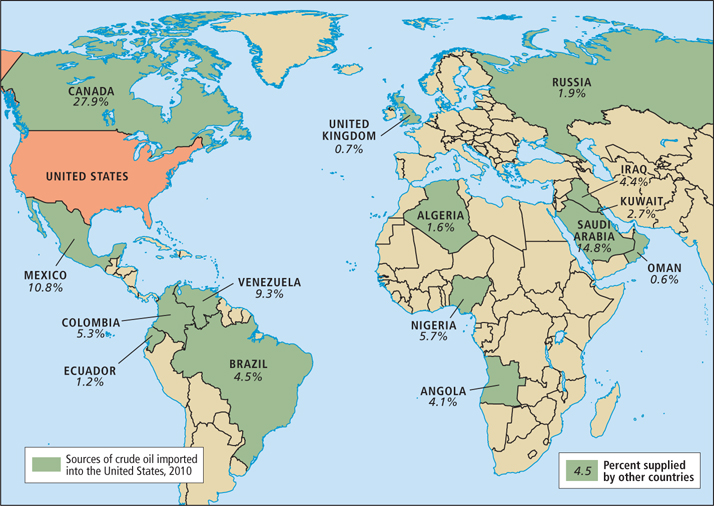

Canada’s role on the world stage is dramatically different than that of the United States, with a more “live and let live” approach. While trade is a similarly strong motivator for Canada’s foreign policies and foreign aid projects, Canada has far fewer strategic military interests abroad. Arguably, Canada’s greatest geopolitical impact comes from its ability to influence the United States. As the largest trading partner of the United States, and one with considerable energy resources, Canada has helped to reduce U.S. dependence on foreign oil. This relationship was highlighted by the 9/11 attacks and the subsequent Iraq War. At that time (early 2000s), about 25 percent of the oil imported into the United States came from the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), which was mostly made up of the countries along the Persian Gulf, where the terrorists had originated. Recent data show that 46 percent of oil imported into the United States comes from countries that are not part of OPEC. Of this 46 percent, Canada supplies 27.9 percent, Mexico supplies 10.8 percent, and 20 other countries supply the remaining 7.3 percent (Figure 2.18A).

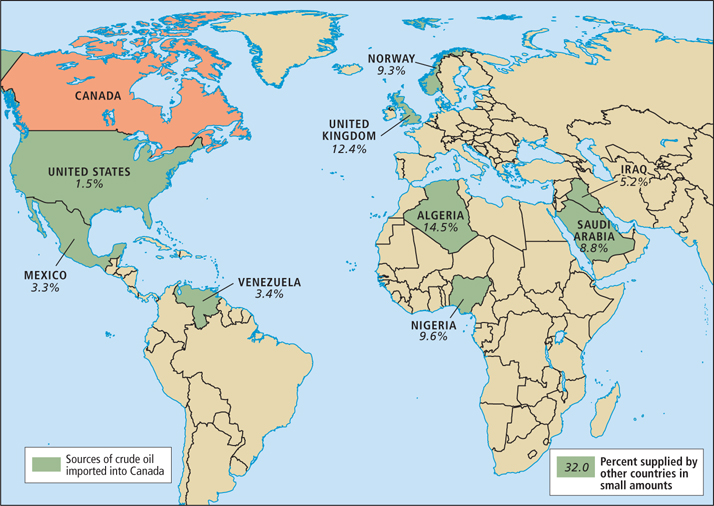

Recent plans to extract fuel from the oil sands of western Canada relate to both Canadian and U.S. strategic interests in reducing dependence on foreign oil. The oil sands could potentially double the amount of oil that Canada exports to the United States and remove much of Canada’s need to import oil. The main reason that Canada imports any oil at all is that most of its oil fields are in the west, far from Canadian population centers and closer to U.S. facilities that can refine the oil. Most of this oil stays in the United States, though some is sold back to the more heavily populated eastern provinces. The rest of the oil imported into Canada comes mostly from OPEC sources. This dependence makes many people in both Canada and the United States uncomfortable, especially given the often antagonistic relationships both countries have with the Persian Gulf states. Thus, despite the many environmental costs of developing Canada’s oil sands, both the United States and Canada have strong strategic and economic interests in doing so.

Challenges to the United States’ Global Power

A number of challenges to U.S. global power have emerged in recent decades. The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan exposed the limits of the United States’ ability to bring about change in less powerful countries. Meanwhile, a new alliance is challenging the United States and its allies in Europe.

Immediately after the attacks on New York City and Washington, DC, on September 11, 2001 (9/11), the international community extended warm sympathy to the United States and generally supported then-

Although NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) forces (including Canadian troops) joined U.S. forces in Afghanistan, the war proved difficult to resolve because of heavy resistance from tribal leaders within the country and from militant Muslim insurgents in adjacent Pakistan. Some of the loss of momentum in Afghanistan can be attributed to the fact that in the spring of 2003, President Bush brought the War on Terror to Iraq, and U.S. strategic attention and troop support were diverted.

The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan eventually ended with few concrete gains, despite heavy losses of civilian life. U.S. combat troops withdrew from Iraq in 2011 and from Afghanistan in 2014, and both countries remain plagued by violence. In the case of Iraq, most of the lucrative contracts to develop the country’s oil resources went to companies in countries that opposed the war, such as China. Meanwhile, international public opinion polls showed that the U.S. image abroad was badly damaged by what was seen as an unjust war aimed mainly at controlling the resources of foreign countries (see Figure 2.17A, B, and map).

Since 2001, an alliance of four countries has emerged as a symbol of growing resistance to the global power of the United States and its allies. Together, these countries—

39. CONSEQUENCES REPORT

39. CONSEQUENCES REPORT