3.6 POWER AND POLITICS

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 3

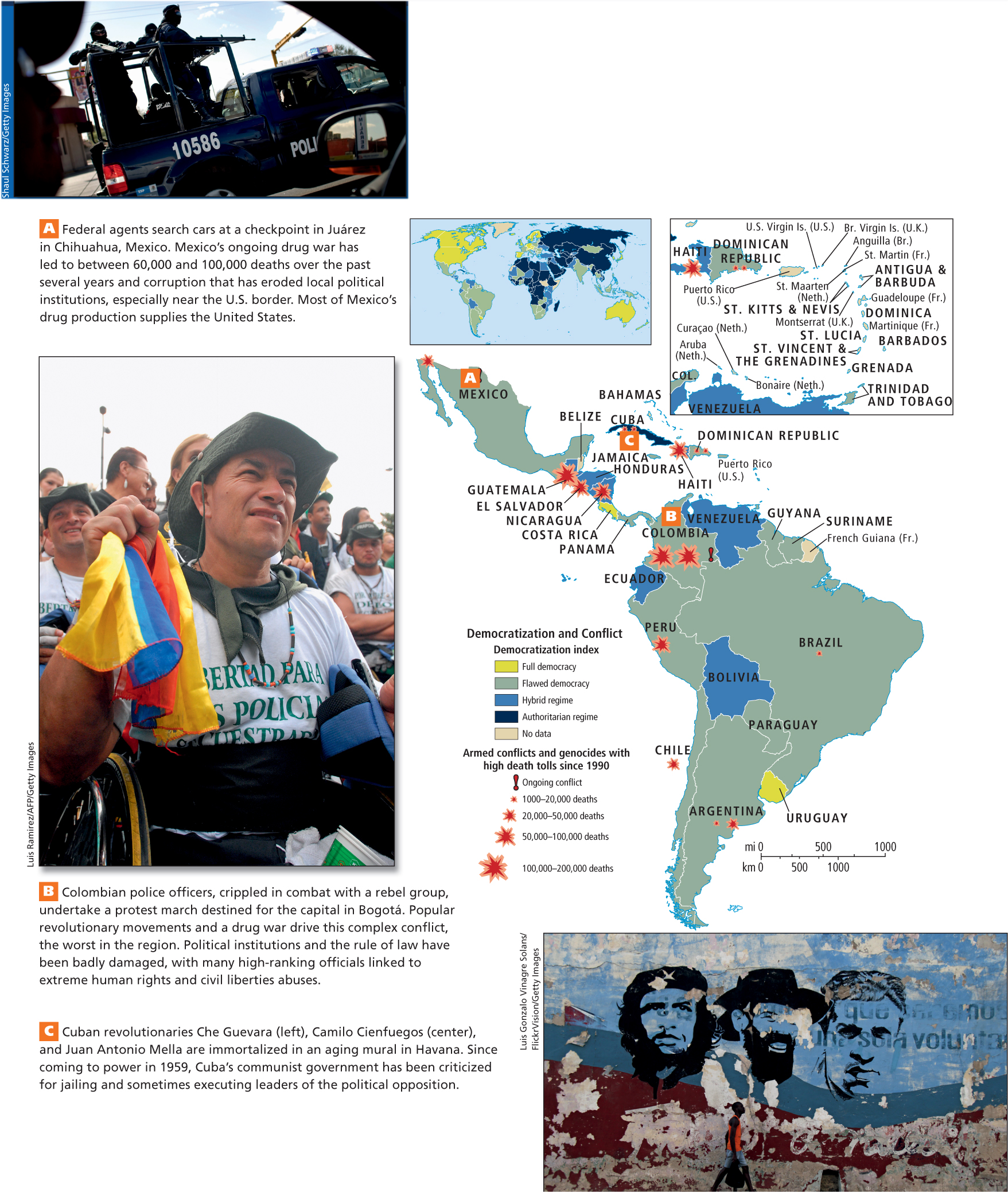

Power and Politics: After decades of rule by elites and the military, punctuated by disruptive foreign military interventions, political freedoms in Middle and South America are expanding. Almost all countries now have multiparty political systems and democratically elected governments. However, the international illegal drug trade continues to be a source of violence and corruption in the region.

In the last 30 years, there have been repeated peaceful and democratic transfers of power in countries once dominated by rulers who seized power by force. These dictators often claimed absolute authority, governing with little respect for the law or the rights of their citizens. Their authority was based on alliances between the military, wealthy rural landowners, wealthy urban entrepreneurs, foreign corporations, and even foreign governments such as the United States.

dictator a ruler who claims absolute authority, governing with little respect for the law or the rights of citizens

Although a slow expansion of political freedoms has transformed the politics of the region, problems remain (as seen in Figure 3.19). Elections are sometimes poorly or unfairly run and their results are frequently contested. Elected governments are sometimes challenged by citizen protests or threatened with a coup d’état, in which the military takes control of the government by force. Such coups are usually a response to policies that are unpopular with large segments of the population, powerful elites, the military, or the United States. In the last decade, coups have been threatened in Honduras, Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, and Bolivia; but more recently, peaceful democratic elections have become the norm in this region.

THINKING GEOGRAPHICALLY

Use the Photo Essay above to answer these questions.

Question 3.13

A What evidence can you find in the photo of a violent situation in Mexico?

Question 3.14

B What are the indications that these men were once involved in violent combat?

Question 3.15

C Why would the Cuban government lionize these men in a mural?

coup d’état a military-

Hugo Chávez and Venezuelan Politics In Venezuela, the landslide election of Hugo Chávez as president in 1998 brought profound change to the country. Elites had long dominated Venezuelan politics, and profits from the country’s rich oil deposits had not reached the poor. One- 66. SOCIAL PROGRAMS AT ROOT OF CHÁVEZ’S POPULARITY

66. SOCIAL PROGRAMS AT ROOT OF CHÁVEZ’S POPULARITY

Chávez was reelected in 2000, and then briefly deposed in a coup d’état in 2001 in which the United States participated covertly. He was quickly reinstated, however, by a groundswell of popular support among the large underclass who stood to benefit from his policies. His presidency was sustained in a referendum in 2004 and again in the landslide election of 2006. In 2009, voters approved a constitutional amendment removing presidential term limits, thereby allowing Chávez to run for president indefinitely. Some saw this as a triumph of the populist movement, others as a loss for democracy and a drift back toward dictatorship (see the Figure 3.19 map). Hugo Chávez died in March of 2013 from cancer after having been treated numerous times by specialists in Cuba.

The Drug Trade and Conflict

The international illegal drug trade is a major source of violence and corruption throughout the region. The primary drugs being traded are cocaine, heroin, and marijuana. Most drugs are produced in or pass through northwestern South America, Central America, and Mexico. Figure 3.20 illustrates the geographic distribution of cocaine seizures in 2008. (Note: Such seizures may not reveal activity in areas where law enforcement is lax or entirely co-

Production of cocaine and heroin is illegal in all of Middle and South America. However, public figures, from the local police on up to high officials, are paid to turn a blind eye to the industry. Most coca growers are small-

In Colombia, the illegal drug trade has financed all sides of a continuing civil war that has threatened the country’s democratic traditions and displaced more than 1.5 million people over the past several decades (see Figure 3.19B). Mexico also has faced increasing threats to its political stability from drug cartels that control a hugely profitable U.S.-oriented drug trade (see Figure 3.19A).  72. THOUSANDS KIDNAPPED IN COLOMBIA IN LAST DECADE

72. THOUSANDS KIDNAPPED IN COLOMBIA IN LAST DECADE

U.S. policy has emphasized stopping the production of illegal drugs in Middle and South America and interrupting trade flows rather than curtailing the demand for drugs in the United States. As a result, the U.S. war on drugs has led to a major U.S. presence in the region that is focused on supplying intelligence, herbicides used to destroy drug crops, military equipment, and training to military forces in the region. One consequence of this is that U.S. military aid to Middle and South America is now about equal to U.S. aid for education and other social programs in the region. Drug production levels in Middle and South America, though, are higher than ever, exceeding demand in the U.S. market, where street prices for many drugs have fallen in recent years.

Concerned and informed citizens of Middle and South America have been calling for radical changes in international drug policies, including the legalization of drug use in the main (U.S.) market, which they assert would cause criminals to lose interest in the drug trade. In 2013, Uruguay legalized and regulated marijuana use, cultivation, sale, and distribution in an effort to reduce drug-

Foreign Involvement in the Region’s Politics

Interventions in the region’s politics by outside powers have frequently compromised political freedoms and human rights. Although the former Soviet Union, Britain, France, and other European countries have wielded much influence, by far the most active foreign power in this region has been the United States.

In 1823, the United States introduced the Monroe Doctrine to warn Europeans that no further colonization would be tolerated in the Americas. Subsequent U.S. administrations interpreted this policy more broadly to mean that the United States itself had the sole right to intervene in the affairs of the countries of Middle and South America, and it has done so many times. The official goal for such interventions was usually to make countries safe for democracy, but in most cases the driving motive was to protect U.S. political and economic interests.

At various times during the past 150 years, U.S.-backed unelected political leaders, many of them military dictators, have been installed in many countries in the region. After World War II, worried that Communism would infiltrate Middle and South America, the United States focused special military scrutiny on a number of countries. Since the 1960s, the United States has funded armed interventions in Cuba (1961), the Dominican Republic (1965), Nicaragua (1980s), Grenada (1983), and Panama (1989). Perhaps the most infamous intervention took place in Chile in 1973. With U.S. aid, the elected socialist-

The Cold War and Post– 73. EU SPLIT OVER DEVELOPMENT COMMISSIONER’S PROPOSAL TO NORMALIZE RELATIONS WITH CUBA

73. EU SPLIT OVER DEVELOPMENT COMMISSIONER’S PROPOSAL TO NORMALIZE RELATIONS WITH CUBA

With help from the Soviet Union, Castro managed to dramatically improve the country’s literacy and infant mortality rates and the life expectancy of its population. Unfortunately, he also imprisoned or executed thousands of Cubans who disagreed with his policies, many of whom fled to southern Florida. Following the demise of the Soviet Union, Castro opened the country to foreign investment. Many countries responded, and Cuba is now a major European tourist destination. However, political repression in Cuba persists, and relations with the United States remain distant.

Recent Revolutionary Movements

In response to continued poverty and inequality, and building on Middle and South America’s long history of revolutionary politics, two major broad-

contested space any area that two or more groups claim or want to use in different and often conflicting ways, such as the Amazon or Palestine

The Zapatista Rebellion In the southern Mexican state of Chiapas, indigenous farmers have mobilized against the economic and political systems that have left them poor and powerless. The Mexican government redistributed some hacienda lands to poor farmers early in the twentieth century, but most fertile land in Chiapas is still held by a wealthy few who use green revolution agriculture to grow cash crops for export. The poor majority farm tiny plots on infertile hillsides. In 2000, about three-

The Zapatista rebellion (named for the hero of the 1910 Mexican revolution, Emiliano Zapata) began on the day the North American Free Trade Agreement took effect in 1994. The Zapatistas view NAFTA as a threat because it diverts the support of the Mexican federal government from land reform to large-

In 2003, after 9 years of armed resistance and largely unsuccessful negotiations with the Mexican government, the Zapatista movement redirected its energies toward local nonviolent political campaigns, mainly in Chiapas, to set up people’s governing bodies parallel to local official governments. More than a decade into this process, the Zapatistas have made significant improvements in education, women’s rights, and poverty reduction, thus deepening their support base in the areas they control. While the Zapatistas continue to focus more locally, the movement still has a national voice via campaigns against the political establishment during election years, and has a global reach through the Internet and numerous training programs for supporters of the movement from around the world.

Brazil’s Landless Movement Sixty-

To help these farmers, organizations such as the Movement of Landless Rural Workers (MST) began taking over unused portions of some large farms. Since the mid-

ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

Children and the Landless Movement

In Brazil, the children of those in the MST movement find living in the landless protestor encampments a source of pride and positive identity. They learn both subsistence and leadership skills, gain knowledge of the natural environment, practice communitarian values, and are proud of the stance their parents have taken, as the video by Michalis Kontopodis, “Landless Children/Sem Terrinha,” at http:/

THINGS TO REMEMBER

GEOGRAPHIC INSIGHT 3

Politics and Power After decades of elite and military rule punctuated by disruptive foreign military interventions, political freedoms in Middle and South America are expanding. Almost all countries now have multiparty political systems and democratically elected governments. However, the international illegal drug trade continues to be a source of violence and corruption in the region.

Elected governments are at times challenged by citizen protests or with a coup d’état because policies are unpopular with large segments of the population, powerful elites, or the military.

The drug trade has emerged as a major obstacle to democracy, with huge amounts of illicit cash being used to pay off elected officials, civil servants, police forces, and the military.

Interventions in the region’s politics by outside powers have frequently compromised political freedoms and human rights.

In response to continued poverty and inequality, and building on this region’s long history of revolutionary politics, two major broad-

based rural political movements have arisen in recent years.